![]() Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe includes a lengthy article on Jewish music, which one would expect for a topic that is so closely associated with Jewish culture and history in the region. But the Encyclopedia notes that until the late 19th century, no significant amount of Jewish music was transcribed and little else was written about it in useful forms, so “we know next to nothing about what how music sounded throughout 1,000 years of Ashkenazic history in the region.” [1] By the beginning of the 20th century, and under the influence of other contemporary Western and Central European cultures, Jewish music blossomed in all areas of life: in daily and weekly chants and sung prayers in both domestic and public religious service; in instrumental concert music from weddings to popular recordings to classical conservatory work; and in a wide variety of popular folk music, both vocal and instrumental.

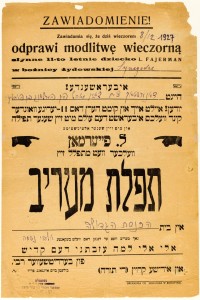

1927 Rohatyn concert poster. [2]

[is] also singing Eli, Eli, the ever popular Yiddish theater hit that was practically an anthem one hundred years ago. Wunderkind cantors were not uncommon. Among the most famous was Moses Mirsky, who moved to London and became one of the most respected voice teachers at one of the big conservatories there. Alto boys were really beloved because when they grew up they became tenors, and duets between the cantor and an alto soloist were very common.

So Rohatyn was not completely off the map of Jewish religious music in the early 20th century.

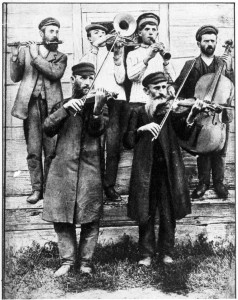

But any discussion about music in Rohatyn should really begin with the Faust Family Klezmorim, who were as close to rock stars as Galician Jewish musicians could get. Anyone who knew pre-war Rohatyn knew of the Fausts, and the band was popular in other towns of the region as well; even people who have never heard of the family or the band know the famous photo shown here. In the Rohatyn Yizkor book section about life within the town, Yehoshua Spiegel easily recalls “the Jewish orchestra”:

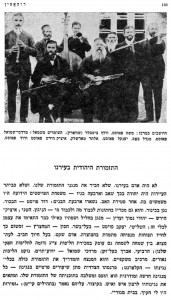

The Faust Family Klezmorim in the Rohatyn Yizkor book. [1:p.140]

There was not a person in our city that did not know the musicians of our orchestra. And in none of the other towns was there such a unique group as this father and his four sons – the well-known members of the Faust family. After the father’s death, the four sons remained. David Faust, the eldest, was the fiddle player, and also used to call the tune at anybody’s wedding. The second son, Itsik-Hersh, a small and delicate man, played the flute, and his lips seemed to have been molded to fit his instrument. The third, Yaakov Faust, stout and powerful, was the trumpeter, and as his cheeks were always puffed up from trumpeting, he was a quiet man, with an endearing smile. When he had time, between festivities, he earned a living selling “tsayg” suits (similar to our khaki suits). The fourth, Mordechai-Shmuel, a young, bearded, bespectacled man with a cultivated demeanor, could read music and conducted and led the orchestra on his instrument – the clarinet. He earned his living on the side giving private music lessons. He pounced on every new and modern melody and incorporated it into the program of his orchestra, and fit his melody to the tastes of each individual. In short, it may be said of them (from Psalm 119): “Thy statutes have been my song, in the house of my pilgrimage.” [3: p.140]

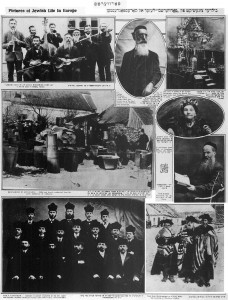

The Faust Family Klezmorim at upper left on page 20 of the 07Oct1923 edition of The Jewish Daily Forward, a Yiddish/English newspaper published in the US.

Elsewhere in the same Yizkor book, Dr. Isaac Lewenter recalls:

Every Jew from Rohatyn would certainly remember the “family band of musicians,” the Faust family. They were the talk of the town – Moshe, Dovid, Itzik-Hersh, Mordecai-Shmuel, and Yaakov. Moshe, the father, was the conductor, Dovid, the fiddler, Itzik-Hersh, the flautist, Mordecai-Shmuel, a multi-instrumentalist and clarinet player, and the little ruffian, Yekel, the trumpet player and drummer. Weddings in Rohatyn reverberated throughout the surrounding countryside. The canopy was set up beside the large synagogue, and the bride and groom were led there amidst a grand parade. The band led the way. The music rang through the streets and raised a great crowd. Children ran ahead and had a great time chasing after the band. It was lively and cheerful in the shtetl. [3: p.91]

And Dr. Golda Fisher remembers:

Can you imagine the sweet joy and the exaltation when, on the morning after “matura’ (graduation from high school), our Jewish orchestra (the Faust brothers) would awaken you with the joyous tunes of Jewish melodies? I do not think that any serenade ever sounded sweeter. […] Yes, the Fausts played at “maturas” and they played at the weddings. They played after the Yom Kippur fast and on any occasion when they might earn a zloty. One of them, who was our violin teacher, often told me about the adventures of his past. He had been in the great land of America and had had a chance to marry a rich girl there, but he preferred to come home and to marry the girl he loved. He often wondered how wise he had been. […] On Yom Kippur, when all of us would run home from synagogue after the fast to rejoice with our families over the delicacies prepared for the occasion, the Fausts would run home to get their violins and go from house to house, playing happy tunes to wish those who could afford this “luxury” a happy New Year. [3:p.23E]

The Rohatyn klezmer group was remembered outside the town as well. Yale Strom, a klezmer revivalist, ethnographer, and hands-on historian of the musical genre has noted [4] two other memories of the Faust family band, in Podhajce (Pidhaitsi) about 50km to the east:

I also recall joyous Jewish weddings that were held in the hall of Gross’ or Schechter’s hotels. The local musicians, Dauber, Kimmel and Leizerl played. At times the Gutenflan brothers from Brzeziny or the Faust kapelye from Rohatyn were brought in. [4:p.301, quoting the Podhajce Yizkor book p.170]

and in Bursztyn (Burshtyn), 20km south of Rohatyn:

The Rohatyner klezmorim were: Moyshele Faust, his sons Duvid, Itsik-Hirsh, Mordkhay-Shmuel, Yankl, and others. For two generations they led brides and grooms to the khupe. [4:p.271, quoting the Burzhtyn Yizkor book p.269]

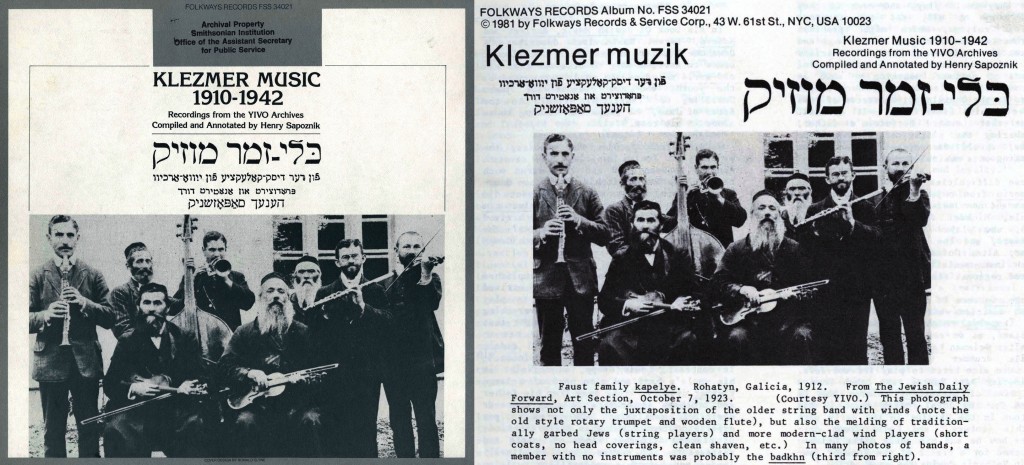

The fame of the Faust Family Klezmorim lived on long after they and the Jewish community they entertained disappeared from Rohatyn. In 1981, the American world-music publishing company Folkways Records (founded and managed by Moses Asch, a Warsaw-born Polish Jew) produced an album of recordings from the YIVO archives called Klezmer Music 1910-1942 [FSS 34021] featuring on the cover… the Faust band photo. And they appeared in the liner notes inside as well, with additional information about the composition of the band and highlighting the contrast between traditional and modernist instruments and dress among the players. [8] Unfortunately the recording features no tunes played by the Faust family, and no other recordings by the musical Rohatyners are known to exist.

Folkways Records album FSS 34021, featuring a photo of the Faust Family Klezmorim and extensive liner notes. [5]

Klezmer musicians at a wedding, playing an accompaniment to the arrival of the groom, Ukraine, ca. 1925. Photograph by Menakhem Kipnis. [6]

After World War I, klezmorim were increasingly integrated into various forms of European musical life, even as they maintained a role in Jewish communal music. Within Jewish society, the main venue for klezmer bands and the primary opportunity for performance and for paying work was the wedding. Apart from weddings, klezmorim performed on holidays such as Hanukkah, Purim, and sometimes on Sukkot, Passover, and at the end of the Sabbath.

YIVO [6] and Strom [4] describe the instruments, roots, structure, and influences of the klezmer genre, and much more information can be had in those references. For a flavor of the breadth of the klezmer repertoire, here is YIVO on the limited surviving klezmer musical documentation (the audio links are playable on the YIVO site):

Incidental documentation has bequeathed some data about a broad southern area from Galicia to Ukraine and Moldova. From this southern region, the genre system and the shape of melodies (along with many specific tunes) are known from the last third or at times the middle of the nineteenth century. In general, the repertoire forms a continuum beginning with improvisations in flowing rhythm (taksim, doyne [listen to recordings]), semifixed rubato melodies (shteyger, zogekhts [listen to a recording]), and improvisations with a rhythmic basis (gedanken); through display pieces based on duple (double) dance rhythms (skotshne [listen to a recording]), nondance moralishe nigunim in triple time (dobriden [listen to a recording]), and Near Eastern rhythmic melodies (terkisher dobriden); and extending to elaborate three-part dance tunes for virtuoso solo dancing or for listening, and dance tunes based on particular group dances. [6]

That term dobriden should sound familiar to anyone who has spent time in Lviv or Rohatyn; it means good morning or good day in Ukrainian, and it was also the name for the elegant and measured tune that the klezmer kapelye played to welcome guests on the morning of (or after) a Jewish wedding. The tune is also called mazel tov, for obvious reasons. [7] In addition to the audio clip above, here is a video clip of one form of the dobriden played on violin in a quartet:

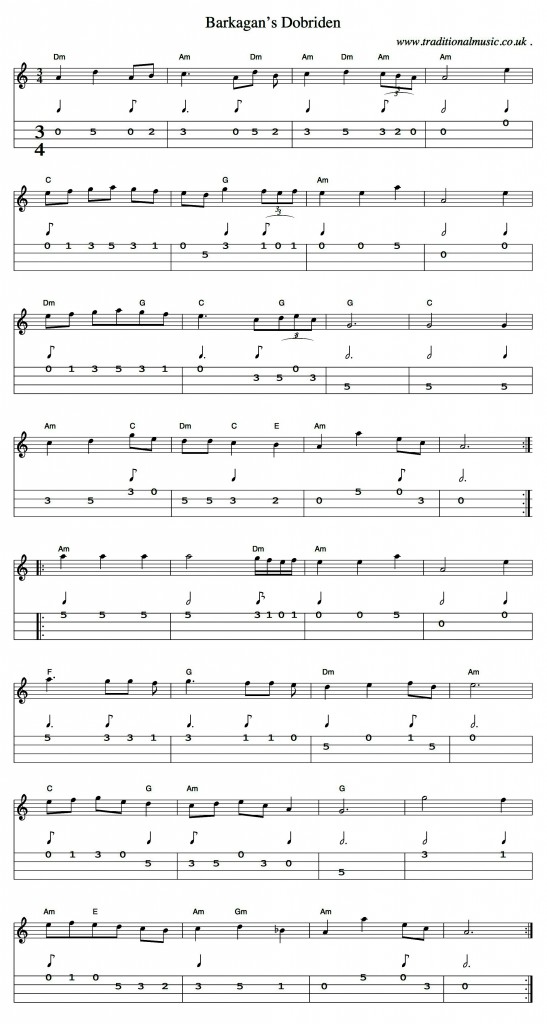

And finally, here is sheet music and tabs for another version of the melody, filtered through the traditional musical styles of England; it sounds like this. Perhaps someone could adapt this music to bring the lovely tune back to Rohatyn?

Barkagan’s Dobriden from the UK. [8]

Sources

[1]: The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe: Jewish Music – An Overview

[2] YIVO Archives: Rohatyn. Maariv service, along with Hebrew and Yiddish religious songs. YIVO RG 28/P/786.

[3] Yizkor Book for Rohatyn: The Community of Rohatyn and Environs (Kehilat Rohatyn v’hasviva); eds. M. Amitai, David Stockfish, and Shmuel Bari; Rohatyn Association of Israel, 1962 (in Hebrew). Online image version hosted by the New York Public Library. Online English version hosted by JewishGen, coordinated by Michael J. Bohnen and Donia Gold Shwarzstein.

[4] The Book of Klezmer: The History, the Music, the Folklore; Yale Strom; Chicago Review Press; Chicago IL; 2011.

[5] Klezmer Music 1910~1942: Recordings from the YIVO Archives; Folkways Records album FSS 34021; compiled and annotated by Henry Sapoznik; Smithsonian Folkways; 1981.

[6] The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe: Traditional and Instrumental Music.

[7] Ilana Cravits; Resources; Types of Klezmer Tunes.

[8] The Traditional Music Library; Sheet music and mandolin tab for Barkagan’s Dobriden.