![]() Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Death, the last milestone of the life cycle, can be frightening for both the dying and the survivors, and is accompanied in Jewish culture by a large tradition of beliefs, ritual, and other responses. The details of observance and practice vary according to each Jewish community; some traditions around death, burial, and mourning are nearly universal across history, geography, and the variety of Jewish religious movements, but the traditions were (and are) striking more for their variation than for their uniformity, even when studied regionally. This brief overview aims to put the Jewish heritage of Rohatyn in context, and to highlight a few specific features of that heritage still visible in Rohatyn today. At the end of this page is a list of sources used in this overview.

Perspectives on Dying and Death

Attitudes toward dying evolved after biblical times, when death was viewed as a kind of sleep, and a blessing if it came in old age. The expression “there are many avenues toward death” mentioned in the Hebrew Bible was later interpreted numerically in the Talmud to mean 903 distinct ways of death, from light to severe, and over time the day and the manner of a person’s death were believed to be omens for the deceased.

Notions of the soul, an afterlife, and a place for the dead to gather are less distinct in early Jewish tradition than some others, but were influenced by kabbalistic thought and by folk traditions; the conceptual origins of some modern views are difficult to trace. In the Hebrew Bible, Sheol, the gathering place, is variously described as a place of oblivion, gloomy and dark, deep in the Earth, and as far from heaven as possible. One’s expectations there are not influenced by one’s behavior while living; the dead merely exist without knowledge or feeling. For many Jews, the greatest pain of death was the separation from and inability to communicate with God.

Core Beliefs Relating to Death

A fundamental principle of Jewish belief, the impurity of the dead, underpins many of the customs related to death and burial defined in halakhic law (for example, Numbers 19). Thus the importance of cemeteries: the dead must be separated by a distance from places of human habitation, and confined to areas for them alone. Similarly the Jewish custom of burying the dead very soon after death; this also relates to the body’s decay and the risk it poses to survivors. Perspectives on the relationship of living persons to the body of the dead have varied, especially between urban vs. rural communities, and in times and places where child mortality rates were especially and continuously high.

Other core principles of Jewish belief include respect for the dead (even a dead person’s body), and care of their survivors. These concepts derive from the broader principles of honor due parents and other elders, the need to alleviate the suffering of others, and the basic equality of all before God. Customs concerning the preparation of the body for burial, the funeral, mourning, and many others still relate to these principles.

Burial Societies, and the Preparation of the Body

In biblical times it was the obligation of a Jewish family to care for their dead and bury or entomb them, but it was also regarded as one of the laws of humanity not to let any one lie unburied. In larger communities it became common for individuals or informal volunteer groups to aid those who would struggle with the effort due to age, poverty, or debilitating grief.

The obligation to bury applies to every corpse, even criminals who have been put to death, the unclaimed slain, suicides, and strangers to the community. To be denied burial was the most humiliating indignity that could be inflicted on the deceased, for it meant “to become food for beasts of prey”. Traditions of compassion thus prescribe burial for all.

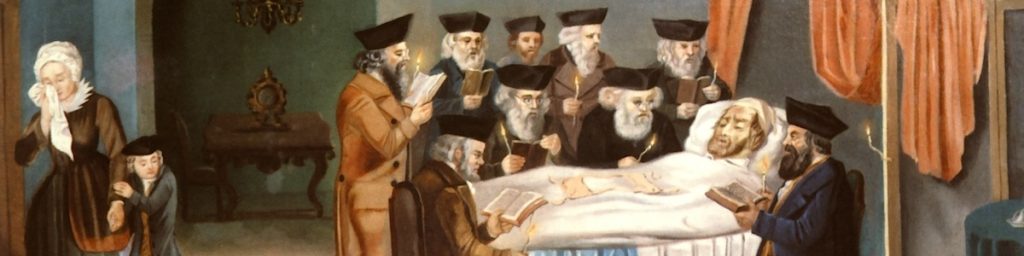

The Prague hevrah kadisha attends to a man at death. Unknown painter, ca. 1772. Image from the Jewish Museum of Prague, via Wikimedia Commons.

An association which took responsibility, on behalf of the entire community, for the preparation and burial of the dead, began in Prague in the 16th century, then spread in Central Europe so that eventually treatment of the dead was entrusted to burial societies in virtually every Jewish community. The early societies called themselves something similar to Hevrah Kadisha’ Gemilut Hesed shel Emet (“Holy Society of Those Who Do Truly Good Deeds”). Over time, the associations gained prestige and took a variety of names, but eventually any mutual assistance burial society became known simply as a hevrah kadisha (“holy fraternity”). The societies continued as the main framework for dealing with illness, deathbed rituals such as confession, preparing corpses, and carrying out burials.

Long-standing Jewish traditions consider the dead defenseless, and, as a sign of respect, a body should not be left alone; it should be watched over constantly, by sun or by candlelight, on weekdays or the Sabbath, until the funeral. In many households, those attending the body (either the family of the dead, or a member of the hevrah kadisha) will recite continuously from the Book of Psalms in shifts during this period. The reading of psalms at this time is viewed in Jewish tradition as an appeal for God’s favor for the sake of the dead.

A wooden coffin at a Jewish burial in Zimbabwe. Source: The Chronicle

Once death has been established by a doctor or the family, mirrors are covered in the dead person’s house, to diminish reflection on the beauty and ornamentation of the flesh. There are three major stages to preparing the body for burial: washing (rechitzah), ritual purification (taharah), and dressing (halbashah). The body is washed with clear water and wrapped in a simple cloth shroud or robe (for men, a kittel), preferably white and of linen; symbolically, this emphasizes the equality of all (rich and poor) in death. No jewelry or cosmetics are applied to the body. A man may also be wrapped in the tallit (prayer shawl) that he prayed in during life. Jewish custom also commonly avoids an open casket before and during the funeral; one tradition suggests this is so that the dead’s enemies may not rejoice at the sight.

Commonly, the casket is a plain wooden box without internal trim or external adornment, and without polished handles. No flowers are added inside the casket. In some traditions, a board is removed from the bottom of the casket, or a hole drilled through it, to quicken the atoning process of decay; some other Jewish communities, especially in Israel, omit a casket altogether. Jewish beliefs about the integrity of a person’s body as a sign of God’s glory, and the necessity of contact with the earth after death to promote atoning decay, cause some Jewish religious movements to avoid autopsy, embalming, or cremation. These restrictions are not universal, especially among the western diaspora (in North America and elsewhere); autopsy prohibitions are sometimes relaxed everywhere when the effort may save the lives of others or resolve a crime.

Cemeteries, Funerals, and Burials

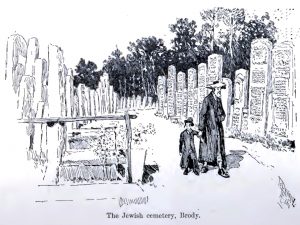

In Hebrew, a cemetery is called bet kevarot (house or place of graves – Neh. 2:3), but more commonly bet hayyim (house or garden of life) or bet olam (house of eternity – Eccl. 12:5). According to Jewish tradition, a cemetery is a holy place more sacred even than a synagogue. Strict laws regarding burial and mourning govern Jewish practice. For Jews, the care of cemeteries is an essential religious and social responsibility. The Talmudic saying “Jewish gravestones are fairer than royal palaces” (Sanh. 96b; cf. Matt. 23:29) reflects the care that should be given to Jewish graves and cemeteries. In normal circumstances, the entire Jewish community willingly shares the protection, repair, and maintenance of cemeteries.

On the other hand, a cemetery is also a place of impurity. Ancient Jewish law requires that a burial ground be at least 50 ells (a distance of at least 25m) from the nearest house. Care should be taken to alert visitors and passersby to its presence (through signs, fences, or other markers). Similarly, visitors should wash their hands upon leaving a cemetery, and many Jewish cemeteries have facilities for that purpose at the gates.

Two views of the old Jewish cemetery of Rohatyn. From a prewar film made by Fania Holtzmann during her visit to Rohatyn and Lwów in the 1930s. Film courtesy the Digital Collection of the Center for Jewish History.

Click on the image to see the film.

Because the cemetery is a holy place and a place of prayer, Jewish customs avoid the use of graves and cemetery grounds for pleasure, levity, or even study. Thus, visitors wear modest dress (including head covering for men), and they do not eat or drink within or near the cemetery boundaries. Jews abstain from extraneous conversation and music or other entertainment, and visitors should avoid stepping over or sitting on gravestones (it is acceptable to sit on benches or other supports near graves). The traditions on these topics all derive from respect for the holiness of the place and for the dead who are buried there.

Identifying the cemetery as holy ground also underlies the traditions which avoid using the place for private purposes. Jews adhering to some religious movements shy from picking flowers and tree fruit which grow by chance in the cemetery, and for these Jews the grass which grows there should be managed (by grazing or cutting) without profit to the Jewish community. The neglect of many Jewish cemeteries in central and eastern Europe today is of course due to the absence of Jewish communities in those towns since the Shoah, but cemeteries lacking ongoing care exist anywhere the founding communities have moved away or been displaced.

Burial should take place as soon after death as possible; if not the same (or next) day, as described variously in the Hebrew Bible, then at most a few days later and only to allow close relatives to gather to pay their respects. In America, many Jewish communities limit the delay to three days at most. Although it is undesirable to postpone a funeral, burials should never take place on the Sabbath or on Jewish holidays.

Traditionally, Jews are buried only in a Jewish cemetery, and ideally among family. Where that is not possible, Jews should be buried apart from the graves of non-Jews. Normally, the earth over a Jew’s grave should not be disturbed, and disinterment is forbidden; where a grave is opened or disturbed by the elements, desecration, or other causes, customs impose the immediate re-burial of the remains. The range of Jewish customs on this point is very broad now, and in some Jewish communities, especially in North America, there are no prohibitions to disinterment, especially to gather family members into common ground.

A Jewish funeral is a symbolic farewell to the dead, often simple and brief. Rather than intended to comfort the mourners (considered impossible so soon after the death, and before burial), the service is directed to honoring the dead. Before the funeral begins, the close family rend their garments or a symbolic ribbon; see more on mourning customs below. A eulogy or hesped may be recited at the home of the dead or at the cemetery (in some communities, at a synagogue), and psalms and a memorial prayer (El malei rachamim) are often recited or sung. The body is escorted to the grave site by mourners before or after spoken ceremony; accompanying the dead is considered a high sign of respect. In many traditional funerals, the casket will be carried from the hearse to the grave in seven stages, with a symbolic pause after each stage.

Although traditions vary significantly regarding the arrangement of graves in the cemetery, one common custom in east-central Europe is to dig the grave so that the body will lie on an east-west axis, with the head at the west end and the feet at the east; this is symbolically if not actually facing Jerusalem. The proper depth of graves is likewise driven more by local custom than prescription. In some places, the density of graves in the confined space of the cemetery necessitated burying recent dead above those already interred; from this the custom developed that later burials should be spaced six hand breadths above the earlier ones.

In the presence of the entourage, the casket is lowered into the grave and the grave is filled; at least the first shovels of earth are placed by mourners, until the casket is covered. A burial kaddish may be recited. In some regions, mourners may place a stone on the covered grave and ask forgiveness of the dead for any injustice they may have committed against the deceased. Upon leaving the cemetery or before returning to their homes, the entourage washes their hands, symbolic of the ancient custom of purification performed after contact with the dead.

The end of the funeral signifies a transition of mourning for the immediate family; condolences are now expressed by the attending rabbi and others in the entourage. See below for more information about mourning practices before and after the funeral.

Mourning

The experience of pain at the death of a loved one is universal. Jewish tradition considers excessive mourning undesirable, and outlines a number of rituals on a specified schedule, to aid close family and friends of the dead to pass through their grief.

At the time of death, a period of intense mourning (aninut) begins and lasts until the funeral. It is assumed the close family is too upset to interact with others; along with taking up the tasks of preparing the body and arranging the funeral, others will avoid expressing consoling words and making any significant show of their own grief. Visitors to the house will stay silent unless the mourners address them directly.

Keriah at the funeral of a Rabbi in Jerusalem. Source: Vos Iz Neias.

At the cemetery or at a funeral chapel, and before the start of the funeral service, it is customary for close relatives of the dead to stand and rend (i.e. tear or cut) their garments in an act called keriah; the biblical Jacob did so when he thought blood on Joseph’s coat meant his son was dead, and David did the same for the death of Saul. The act satisfies the emotional need of the moment, as an outlet for anguish, and for this reason is usually limited to only the close family. Tearing garments can also expose the heart, in a symbolic act which represents actual tearing of the heart, and that the mourner can no longer give love to the beloved. In some communities, the ribbons worn at the funeral represent the garments and are torn instead. The rules of keriah are coded, for who, when, where, and how, so that proper respect and relief can be achieved.

The traditional mourning periods are well defined and calendared. The first period, called shiva (Hebrew for seven), is a time of deep mourning lasting a week from the time the deceased’s family returns home after the funeral. The first meal at the house (seudat havraah, the meal of condolence) is typically prepared by neighbors for the family, and includes foods symbolic of life, such as hard-boiled eggs, bread, and stewed lentils; in some traditions, the lack of holes in the eggs also represents the bereaved’s failure to express grief in words. For the week of shiva, mourners keep their mirrors covered, burn candles, sit on low stools or on the floor, and refrain from working or reading, leaving the house, showering or bathing, shaving, wearing leather shoes or jewelry, listening to music, and sexual relations. It is common for visitors to continue to prepare meals for the house, and to refrain from initiating conversation. The family may lead prayer services at the house, but may also choose not to interact with their visitors.

Two scenes of common customs during the mourning week of shiva, from an animated interfaith guide to Jewish traditions: on the left, sitting on low seats; on the right, covering mirrors. Source: bimbam.com

For the first thirty days after the burial (which includes shiva), during a period known as shloshim (from the Hebrew word for thirty), mourners are forbidden to marry or attend festive meals, and men refrain from shaving or cutting their hair. The dead may be honored by others learning the Torah in their name.

For those losing a parent, a full twelve months (shneim asar chodesh) of mourning is counted from the day of death, during which restrictions continue to apply regarding festive occasions, especially where music is played. Mourners continue to recite the kaddish (a prayer which praises the greatness of God and does not mention death, to highlight that faith continues in the face of death), as part of synagogue services for eleven months.

The anniversary of death on the Jewish calendar is called in Yiddish yahrtzeit or yortsayt, or in Hebrew nachala, and each year on this date close relatives of the dead light a candle for 24 hours and read the mourner’s kaddish. On these occasions, many families also give donations and strive to do good deeds in remembrance of the dead. In some traditions, the family also fasts for the anniversary day.

Graves may be visited at any time; some communities have customs of visiting on fast days and before holy days, and especially at the thirty days and the year anniversary after a death.

Leaving flowers is not a traditional Jewish practice. A widely followed tradition is the placing of a small stone on the grave with the left hand, even on graves of someone the visitor never knew. This shows that someone visited the grave site and is a form of tending the grave. In biblical times, gravestones were not used; graves were marked with mounds of stones, so by placing or replacing them, one perpetuates the existence of the site.

Tombs and Matzevot

Although the placement of stones marking Jewish graves is very common today, it is not prescribed by Jewish law and is not universal; the graves of poor Jews who lack family are sometimes not marked, even today. In the earliest times, no inscribed marker was used, though grave sites were sometimes marked with a plain pillar (mazzebah) or stone to designate the place and as a caution against tumah (Levitical impurity), and flat stones were placed over or beside some graves as a defense against scavenging animals. Later, stone buildings or cupolas were placed over the graves of some wealthy families, and the practice of placing inscribed markers at Jewish graves grew in late Greek and Roman times.

The tradition of placing markers at Jewish graves existed in Europe at least since the end of the first millennium, and was brought with Jews to east central Europe; the practice remained customary but not obligatory, and most cemeteries had some unmarked graves. Common Ashkenazic forms for the markers were shared throughout the region: a vertical matzevah slab of primarily rectangular shape with prominent inscription fields. By the sixteenth century, false sarcophagi were also popular in some localities, and beginning in the eighteenth century, some tombs of exceptional scholars, rabbis, or holy men were built with an ohel (literally, “tent”), a simple structure covering the grave.

The timing of the erection of a memorial stone at a grave site varies regionally and within Jewish religious movements; the earliest is at the end of shiva, but common practice especially in descendants of east central European Jews in western countries is to wait until either the first yahrtzeit or a year after the burial.

The placement and orientation of the matzevah at the grave also varies significantly, even within regions. One common practice in the region around Rohatyn was to place the marker at the head end of the grave, with the inscription facing away from the body, so that visitors do not stand over the body to read the inscription. But contrasting examples can be found in many places, and there are variations even within individual cemeteries. Another confusing element for modern visitors is that some grave markers are not literally “headstones”, but are placed at the foot of the deceased.

Until the 19th century, in east central Europe the most common material for grave markers was wood, except for those honoring the very wealthy. Most matzevot were simple planks with painted images or inscriptions carved into the wood. Given the material’s lack of permanence, very few of these wooden markers endured, so that surviving markers in stone more than 200 years old represent only the wealthier classes. The early stone markers were also painted; little of that paint has survived. The oldest stone markers known in the region around Rohatyn date from the 16th century, in Busk (to the north) and Buchach (to the southeast).

A small sample of the many matzevot styles recovered in Rohatyn. Photos © 2011, 2012, 2014 Jay Osborn.

Figurative art began appearing on matzevot in the region by the mid-seventeenth century, evolving from a formal Baroque style to a Baroque-inspired folk art style which lasted until the Shoah. Many of the stone matzevot fragments being recovered around Rohatyn and returned to the Jewish cemeteries there show architectural elements plus animals, trees and flowers, Jewish ritual objects such as candelabra and ewers, and a variety of other symbols of the names, occupations, and status of the dead. In the 20th century, and especially in the interwar period, the design of some matzevot became more restrained in lettering and devoid of ornamentation, especially when formed of harder materials such as granite.

Until the nineteenth century, grave marker inscriptions were painted or engraved almost entirely in Hebrew (with occasional Aramaic flourishes in the epitaphs of learned elites); some inscriptions betray poor knowledge of the language by the stonemasons. As Jewish religious and social customs evolved in the 19th century in Rohatyn and elsewhere in eastern Galicia, and especially with the advance of assimilation and divisions within Jewish communities within towns, other languages appeared in mazevah inscriptions, including German (in Hebrew characters) and, in the interwar period, Polish (in Latin characters).

Over centuries, epitaphs on the stones adopted a standardized format, with an opening formula, a closing formula, and an information block with the key names and dates of the deceased. Set phrases were used in descriptions of the deceased, often filling the majority of the epitaph, and distinguishing characteristics were rare; sometimes a famous or well-respected relative is named, aiding the identification of the deceased. A helpful feature for modern study of the epitaphs: often the poetic praises of form an acrostic, in which the name of the deceased is spelled by the first letter of each line.

For more information on the art and meaning of matzevot in Rohatyn, see our page Written in Stone.

This page is part of a series on Jewish Culture in Rohatyn and beyond.

Sources

YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe: articles on Lifecycle; Death and the Dead; Tombstones

Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-existence; Paul Robert Magocsi and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern; University of Toronto Press; Toronto, 2016; p. 109-111, 114-115, 121-122.

Jewish Encyclopedia; Isadore Singer, ed.; Funk & Wagnalls Co.; New York, 1901-1906; online edition: articles on Death (Views and Customs Concerning); Sheol; Burial; Disinterment; Cremation; Cemetery; Tombs; Tombstones; Funeral Rites; Mourning; Kaddish

Prague Jewish Cemeteries (Pražské židovské hřbitovy); text by Arno Pařík and Vlastimila Hamáčková; photos by Dana Cabanová and Petr Kliment; Židovské muzeum v Praze; Prague, 2008.

Wikipedia: articles on Sheol; Use of Psalms in Jewish Ritual; Bereavement in Judaism; Kaddish; Shiva; Kittel

Jewish Virtual Library: article on Death

Rabbi Moyshe Leib Kolesnik; personal communication, 04Jan2017.

Chabad.org: article on The Jewish Way in Death and Mourning

Nekropol.com: article on Jewish Traditions: Death and Mourning (in Russian)

U.S. Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad: Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine, 2005, p. 31.