![]() Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Introduction

Several thousand Jews from Rohatyn and a dozen surrounding towns and villages were shot to death in Rohatyn in 1942 and 1943, and buried in mass graves. Between those two “Holocaust by bullets” events, another roughly two thousand Jews were deported from Rohatyn on two trains in 1942 to the death camp near Bełżec, where they were killed in gas chambers and then buried in huge mass graves with almost a half million other victims. The Nazi authorities kept no records of the individuals killed at the camp. Beginning in late 1942 and continuing to summer 1943 they exhumed corpses and cremated them, crushing the bones before reburial; then they built a farm over the camp to mask the site. In July 1944, ahead of the Red Army advance in the area, a Soviet aircraft bomb fell on an ammunition train at the camp station in 1944, destroying the station and whatever documents it had held. For lack of information, history was nearly silent about this chapter of the Shoah in Rohatyn and Galicia, but considerable research in the past few decades has recovered some of what was lost and pieced together a partial picture of the death camp and the origins of its victims.

The train station in Rohatyn (which now seldom handles passenger service) is a heritage site of the Holocaust, as is the death camp near Bełżec (now a museum and memorial site); the locations of those sites are listed and linked below. For many Jewish descendants who lost family members in the deportations of 1942, the route their relatives traveled to their deaths also holds special commemorative meaning. The likely wartime rail track connecting Rohatyn to Bełżec is detailed in a map further down on this page.

- Rohatyn’s train station: 49.3997, 24.6215 (49°23’58.9″N 24°37’17.4″E)

- the former death camp, now the Museum – Memorial Site in Bełżec: 50.3736, 23.4583 (50°22’25.0″N 23°27’29.9″E)

During 1942, Rohatyn ghetto roundups were ultimately lethal. Jews survived only by hiding and evading the roundups, so no survivors were witness to any of the events which followed them. On the transports from Rohatyn, we are aware of no one who escaped the locked train cars en route and survived, and arrival from Rohatyn at the Bełżec camp also meant certain death. Most of the information about these heritage sites comes from post-war academic histories, especially the late Robert Kuwałek’s monograph Death Camp in Bełżec (2016), with additions and updates from Dr. Ewa Koper of the Museum – Memorial Site in Bełżec. Objective histories are supplemented by limited information in the Rohatyn Yizkor Book and other memoirs, and in the video-recorded testimonies of Jewish survivors and Ukrainian eyewitnesses, although nearly all references to the deportations are second-hand at best, and often conflicting. Our sources are listed in our history pages and in our pages of resources for further study.

Read a timeline history of the Holocaust in Rohatyn

Read a history of the Rohatyn-origin transports to Bełżec (TBW)

Read summaries of Jewish and other memoirs of wartime Rohatyn

This article is part of a series on Rohatyn’s Jewish heritage on this website. To view the Rohatyn train station as part of the broader Jewish heritage of the town and the district, see this modern interactive map of the heritage sites.

The Train Station in Rohatyn

Rohatyn has had rail service and a station house south of the town center for more than 125 years. For much of that time, the trains were an important transportation and communication resource, originally connecting Rohatyn to the network of Austrian Empire rails (including Lemberg/Lwów/Lviv, Vienna, and Budapest), then to cities in newly-independent Poland (including Warsaw and Vilnius), and after World War II to locations within the Soviet Union (including Kyiv, Minsk, and Moscow).

Rohatyn was the largest midline station on an east-west track connecting Khodoriv (former Chodorów) to Berezhany (former Brzeżany). A historical map of the region shows no rail in Rohatyn in 1880; the north-south line through Khodoriv is attached to an eastbound spur which ends 2km from the Khodoriv station. But by 1893, another map shows the completed rail line through Rohatyn, as well as its station house. Because the 1893 map is based on a geological survey, it also shows how the rail line follows folds in the earth surface.

The rail line through Rohatyn appeared on regional maps between 1880 and 1893.

The terrain also dictated how the east-west line intersected or bypassed existing towns and villages as the rails were laid in the late 19th century. Traveling from Khodoriv to Berezhany today, the route passes through Pryozerne (former Psary), bypassing most other area villages before jogging south to Rohatyn; continuing eastward, the line runs through Putiatyntsi, near to Pukiv, turns north through Lopushnia with a stop in Pidvysoke, then turns east again between several villages before heading north once again through Potutory into the main station in Berezhany. Many people in the area, even in the 19th century, would have been familiar with all of these places.

Railroads were a valuable military asset for all armies in World War I, and it was essential to deny rail service to opponents, so the rails and station in Rohatyn were targeted for damage along with the rest of the town. Photographers active during the Great War were fascinated by ruins; Rohatyn was repeatedly photographed because it was crossed by the eastern front several times, and retreating armies burned the town mercilessly as they left. After Rohatyn changed hands in 1914 and 1915, the battle front stagnated between Rohatyn and Ternopil, and the entrenched Central Powers camped nearby, documenting the devastation in Rohatyn in 1916 for their leaders in Vienna and Berlin. The damaged station house was among the startling scenes captured.

After WWI, like other essential infrastructure elements of Rohatyn, the tracks and the station were repaired, and Rohatyn was reconnected to Europe via the rail system of the Second Polish Republic. In the interwar period (1918~1939), the small park at the crossing of the rail lines and the main north-south road was a favorite place for couples and youth groups to stroll and have their picture taken, and many Jewish descendants today have historical photos of family members enjoying the park. The rail line and Rohatyn’s train station had already been in service for five decades when eastern Poland was invaded in 1939 by the Soviet Army, and World War II began.

When Germany betrayed the Soviet Union in June 1941 and attacked the Soviet Army, the Soviets fled from Rohatyn; the town became part of Germany’s General Government in early July. The new German command forced Jewish boys to gather and move heavy ammunition, including live rounds, which the Soviet Army had abandoned at the Rohatyn train station during their retreat.

Wartime Deportations of Jews from Rohatyn and Nearby Towns

The conditions and events which constitute the Holocaust in Rohatyn began immediately after the arrival of the German Army in 1941. A ghetto was formed west of the town square in August, displacing and incarcerating all Rohatyn Jews. In late 1941, Jews from Cherche (Czercze), Potik (Potok), Babyntsi (Babińce), Zalypia (Zalipie), and Pidkamin (Podkamień) were forced into the Rohatyn ghetto as well. Most of the Jews in the ghetto, more than three thousand women, men, and children, were rounded up, marched, and shot to death on 20 March 1942, then buried in mass graves which had been previously dug at the killing site in fields southeast of the town center.

Afterward, the situation for the several hundred Jews still in the ghetto was dire. In May 1942, hundreds of Jews from Kniahynychi (Knihynicze) were forced into the Rohatyn ghetto. Disease and hunger incapacitated and killed many of those who were imprisoned. Then the forced deportations to Bełżec began.

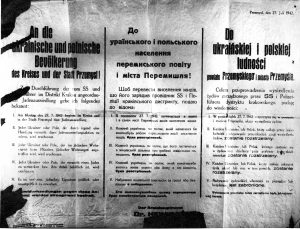

Announcement to Ukrainians and Poles of an imminent deportation of Jews from Przemyśl in July 1942. Source: Yad Vashem.

A major component of the German plan to exterminate all of the Jews of occupied Poland, code-named Aktion Reinhard, was managed by two departments of the SS and police leadership which created the infrastructure to transport Jews, mostly by rail, from wartime ghettos to purpose-built killing centers equipped with gas chambers. Most of the work of Aktion Reinhard was conducted in secret, without published orders, away from major population centers, and with false descriptions, paperwork etc. to minimize mass hysteria in the victims. Public notices about the deportation orders, for example, were labeled by German authorities as “Jewish resettlement” but without specific destinations. Announcements also threatened death by shooting of any Ukrainian or Pole who interfered with the roundups, or attempted to assist Jews or plunder their property. Jews were permitted to bring a small number of belongings, including money and valuables, further masking the true purpose of the train journey.

Jews in Lublin forced onto a deportation train to Bełżec. Source: Yad Vashem.

The death camp at Bełżec was the final stop for transports from ghettos in the southern portion of the General Government, particularly Distrikt Galizien (former eastern Galicia) where Rohatyn was situated, and from transit ghettos southeast of Lublin. Bełżec was on the main Lviv-Lublin rail line, which connected to branch lines under the control of the German Ostbahn railway system, appropriated from the Polish National Railways and forming a sub-unit of the Deutsche Reichsbahn (German National Railway).

The deportations from Rohatyn were typical of the process used throughout Aktion Reinhard. Gestapo or other armed police entered a ghetto and rounded up prisoners for transport, searching houses and shooting anyone who fled or did not follow orders. The gathered prisoners were then marched or trucked to the local train station under heavy guard, packed into freight or cattle cars without food or water, and sealed in with little ventilation in the cars. Smaller trains of deportees were joined with cars from other towns to create large coupled shipments. Deportation trains were given low priority for movement, after goods shipments and military transports, causing long delays in transit. Injuries and shootings during forced loading plus suffocation in transit caused many of the prisoners to die on the deportation trains; one German witness noted more than 20% of prisoners on one large transport from the Lviv ghetto dead on arrival at Bełżec.

Two deportations from the Rohatyn ghetto followed this process, the first on:

21 September 1942: A Rohatyn ghetto roundup under heavy Gestapo control the previous night captured roughly 800 Jews, mostly from Rohatyn and Kniahynychi, and loaded them onto cars at the train station. These victims were joined by others rounded up and transported in simultaneous actions in Burshtyn (Bursztyn), Bukachivtsi (Bukaczowce), and Bilshivtsi (Bołszowce), making a total of roughly 1300 people transported, plus several hundred more shot during the roundups and at train stations. Larger transports were also assembled elsewhere on the same day, adding roughly 3700 more victims to the total, from ghettos in other region towns: Berezhany (Brzeżany), Pidhaitsi (Podhajce), Kozova (Kozowa), and Narayiv (Narajów). There were no survivors of the transport, but some Jews survived the roundup in the Rohatyn ghetto by hiding.

In October, the remaining Jews surviving in the ghettos of Burshtyn, Bukachivtsi, and Bilshivtsi were moved to the Rohatyn ghetto; the ghetto was reduced in area, further cramping prisoners together and compounding problems with sanitation and disease. Deportations from other regional ghettos continued, including from the nearby towns of Berezhany (on 04 December, more than 1000 victims) and Peremyshliany (Przemyślany, on 05 December, about 3000 victims). These were followed soon after by a second deportation from Rohatyn to Bełżec on:

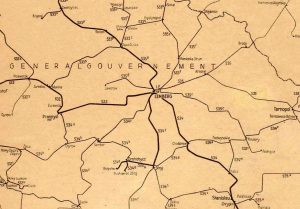

Excerpt from a wartime German railway map of the occupied General Government. Rohatyn is on line #534p between Chodorów and Podwysokie.

Source: Polish national railways map database.

08 December 1942: Gestapo and other police again entered the Rohatyn ghetto with guns and searched all the houses, gathering many Jews and shooting others. Again the prisoners were marched or trucked to the Rohatyn train station and pressed into freight or cattle cars, some 1400 or 1500 total victims, and sent to Bełżec. Again there were no survivors of the transport, but some Jews survived the roundup in the Rohatyn ghetto by hiding.

All deportations to Bełżec ended two days later. On 15 December, the German authorities banned all trains in the General Government except Wehrmacht military transports (to support the combat at Stalingrad), and because the mass graves at Bełżec were at full capacity. Apart from dates and approximate numbers of victims, nothing else is known from records about the two transports from Rohatyn to the death camp.

The end of deportations did not mean the end of killing in Rohatyn. After further ghetto area reductions, the ghetto was emptied in early June 1943 in a mass roundup and killing operation at a remote industrial site to the north of Rohatyn. The ghetto was mostly leveled with fire and explosives; the few survivors fled to the forests or hid in area homes and barns. German forces remained in control in Rohatyn for another year.

The Route to Bełżec and Oblivion

Polish regional maps from the 1920s and 1930s indicate the likely rail route which the deportation trains took in 1942 from Rohatyn and nearby towns. Some variation of the route around Lemberg/Lwów/Lviv was possible, for example to divert able-bodied Jewish men at the Klepariv (Kleparów) station to factories at the Janowska forced-labor camp. It is not known whether any Rohatyn-area Jews left the deportation trains to this end.

On 21 September, Jews from Burshtyn would have been trucked to Rohatyn or Bukachivtsi (the nearest rail stations). Bukachivtsi Jews may also have been trucked to Rohatyn, or transported by rail to Khodoriv to join the Rohatyn cars. Jews from Bilshivtsi in the same deportation event may have been trucked to Rohatyn, or transported by rail to Rohatyn (via Lopushna) or to Khodoriv (via Halych). The larger transport (from Berezhany, Pidhaitsi, Kozova, and Narayiv) on the same day may have traveled independently, or may have coupled with the Rohatyn train at any of several possible stations north and west of Rohatyn. The deportation from Rohatyn on 08 December would likely have traveled the direct rail route.

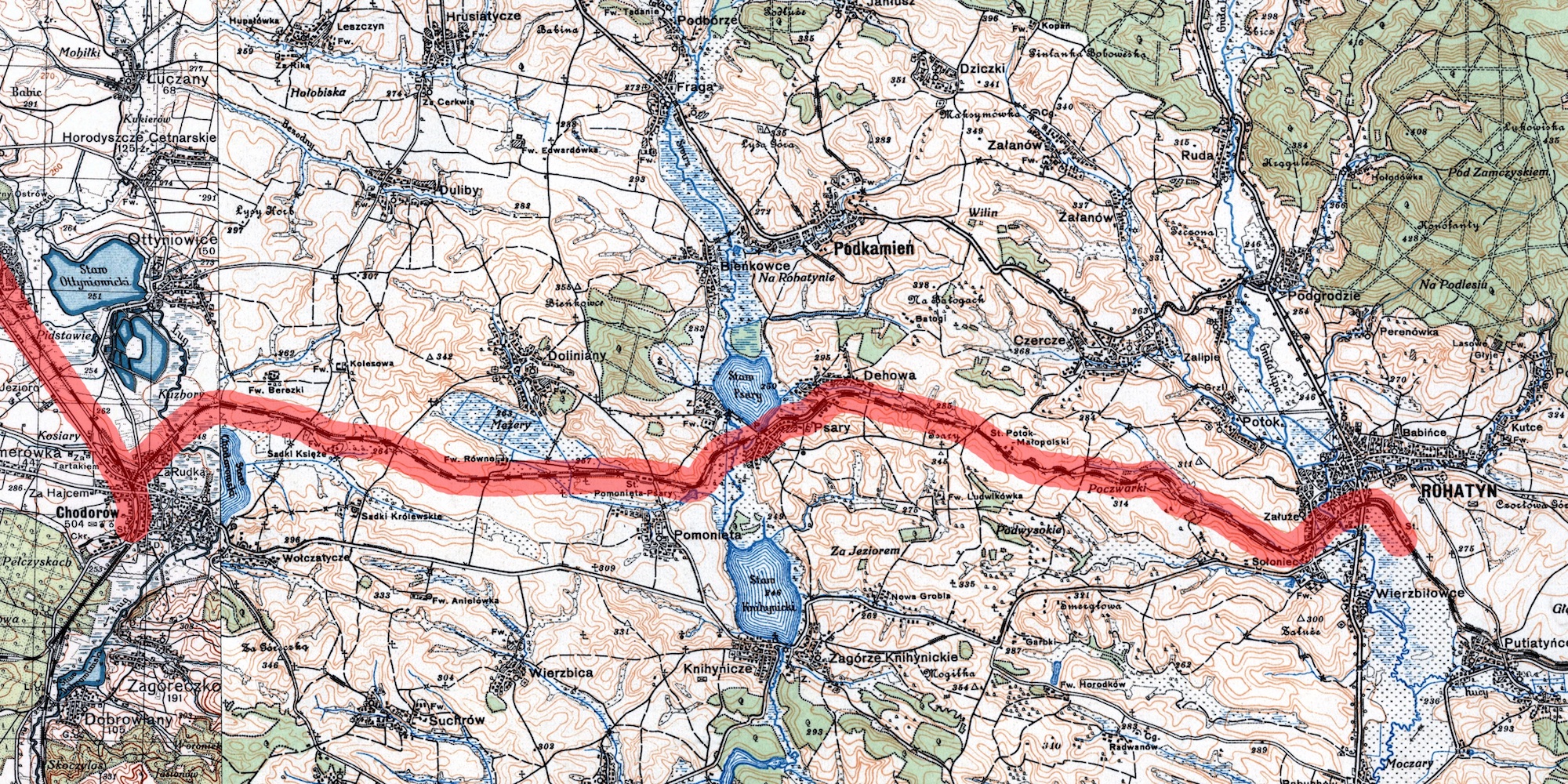

The journey from Rohatyn to Bełżec by rail was roughly 160km (about 100 miles). With low transit priority and unrecorded logistics, the travel time may have been one to several days; average deportation transit times to Bełżec from all origins were four days, with no opportunity for the deportees to exit the cars for any reason. As shown on the map here, the most likely route from Rohatyn was initially westward to Khodoriv, then northward through a series of villages west of Bibrka (Bóbrka), approaching Lviv from the southeast and wrapping clockwise around the city to reach the main interchange and the Klepariv station at the west side of the city center.

From Lviv, the rails headed north again through gaps in elevated terrain, then headed northwest, through stations at the outskirts of Kulykiv (Kulików) and Zhovkva (Żółkiew) before reaching Rava Ruska (Rawa Ruska), near the historical border between Austrian Galicia and Russian Poland. The deportation trains may have been held at any of these stations to allow other rail traffic to pass. From Rava Ruska, it was a short passage of roughly 25km out of Distrikt Galizien and through villages and marshland to the train station in the town of Bełżec, then back southward on a half-kilometer spur to the camp station siding and ramps.

The start of the deportation train route from Rohatyn to Bełżec in 1942. To see the entire route on an interactive map, click on the image above. The map can be panned and zoomed to follow the route closely. A slider in the upper right corner of the window can be moved to see the satellite image underneath. Composite image and map © 2019 RJH.

The Memorial Site in Bełżec, on the grounds of the former camp. Photo © 2019 RJH.

Jews arriving at Bełżec were led to believe they were at a transit camp, for disinfection, after which they would be sent to labor camps. Any contact between the deportees and local townspeople was forbidden. SS and camp guards opened the train car doors at the siding and quickly emptied the cars, beating Jews to hurry them along. The deportees were herded into undressing barracks (men in one, women and children in the other) by guards and Jewish prisoners; the naked women were then routed through barbers’ barracks where their hair was shorn by other Jewish prisoners. Signs and prisoners guided the deportees through each step, with false information and processes designed to keep them calm through to the “disinfection” process. Finally, the deportees were forced through corridors and into the gas chambers by guards and SS with whips and bayonets, where they were killed by exposure for about 20 minutes to concentrated exhaust from a diesel engine, i.e. carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide.

When the gas chamber doors were opened, Jewish prisoners used long hooks to drag the corpses out of the chamber and to open the mouths of the victims. The prisoners extracted gold teeth and searched body orifices for hidden valuables. Then the bodies were dragged to deep pits dug near the gas chambers and stacked until the mass graves were full, after which gasoline or other flammable liquids were poured over them and lit on fire. The overall process typically took two to three hours from the opening of the train cars to the placement of corpses in the mass graves. A separate group of a few dozen Jewish prisoners sorted the deportees’ belongings for cash, precious metals and jewelry, and even personal items such as mirrors, combs, toothbrushes, and spoons, all of which were inventoried and shipped to warehouses (cash and gems were sent to the Reich Bank in Berlin).

After initial trials and adjustments, at its peak operation the death camp at Bełżec was capable of killing up to 10,000 Jews per day. Secrecy during the war and an absence of surviving records makes it very difficult to assess the total number of victims, even today. An intercepted coded telegram sent by the top manager of the Aktion Reinhard transportation network, SS major Hermann Höfle, to Adolf Eichmann and a leader of the German security police on 11 January 1943, indicated that the number of Jews sent by rail to Bełżec in 1942 was 434,508. Post-war research has shown that Deutsche Reichsbahn figures of deportees on Holocaust trains were based on cursory counts during loading at the ghetto stations, and Höfle’s precision was not justified. However, research through 2016 supports a total near to Höfle’s number, while acknowledging that information about additional transports may not have been found, and may never be.

By the end of the war, almost no trace remained of the camp, its structures and killing machinery, or its nearly half a million victims. In the summer of 1942, Heinrich Himmler’s order to remove evidence of atrocities at sites of mass killing was extended to the death camps of Aktion Reinhard. The mass graves at Bełżec had already posed a problem to the German administration, as the pits were unable to contain the huge number of corpses produced by the killing process, which peaked in August; in the warm months of summer and fall, the stench from rotting flesh permeated the camp and the adjacent town. In November, the decision was made to burn the corpses; special racks were built using sections of rails and ties from the town railroad station. Bodies were exhumed using a power shovel and carried to the racks, where they were burned, probably with diesel oil. The fires burned continuously, day and night, through winter and into March 1943, leaving a strong memory of smoke and terrible odor among the town’s residents. Residual bones were ground with a grain mill, and the bone dust and ash were reburied in the mass grave pits. The German command apparently believed all the corpses had been burned, but archaeological excavations in the late 1990s found human remains at the bottom of some of the pits.

Symbolic epitaph of names of the dead at the ohel niche of the Bełżec memorial site. Photo © 2019 RJH.

After the cremation was finished, the SS liquidated and masked the camp by dismantling the buildings and planting trees; records were also destroyed before the German military and police withdrew. To deter local townspeople from digging for valuables at the camp, the SS returned, to station guards at the camp site. A farmhouse was built and a working farm was installed on the grounds; the Volksdeutsch farmer fled when the advancing Soviet Army came near, in July 1944. Although there had been rumors about what was happening in the camp during its operation, few details reached the ghettos in Distrikt Galizien, and the Jewish survivors who were not deported only began learning facts after the war was over. Despite ongoing research, an absence of information continues to shroud the Bełżec camp in considerable mystery; the names and lives of its victims remain mostly lost to oblivion.

Rohatyn’s Train Station Today

The rail line through Rohatyn still serves train passengers at the station, but only on selected days of the week (Friday and Sunday, in 2019). Both passenger trains and freight trains still travel the rails through Rohatyn between Khodoriv and Ternopil as they have for more than a century; transfers can be made at those terminal stations to other destinations in Ukraine and abroad. Passing trains are not common in Rohatyn, but frequent enough that the road crossing at vul. Halytska south of the town center is still manned, for safety.

To date, no plaque or memorial marker has been placed at the train station in Rohatyn to commemorate its role in the Holocaust.