![]() Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Famine began in the ghetto. […] On the streets of the Rohatyn ghetto, people swollen from hunger and suffering from serious ailments were a massive and common phenomenon. […] Lack of food, unsanitary living conditions led to the emergence of infectious diseases – dysentery and typhus. […] Extreme lice was raging. People died without accounting and statistics. Weakened physically and spiritually, they died after two or three days of illness and were stacked like firewood on a special van and taken to the cemetery. Buried in mass graves. They were buried without mourning and traditional Jewish rites. It is difficult to say today what was better – to continue the torment, or rather to die and put an end to life’s problems. Looking ahead, I will note what we already know: in the winter of 1942-1943, a good half of the ghetto’s inhabitants died of typhus. [Arsen, p.187]

Introduction

The etymology of the word ghetto is not known with certainty, but what is known is that it derives from Italian and was first applied to the segregated and restricted Jewish residential area of Venice; eventually the term broadened to mean a part of a city where any minority group lives, often through some form of social or political pressure, and now it typically means a city area characterized by poverty. The most notorious ghettos in world history were the Nazi-ordered Jewish ghettos of Europe, a systematic element of the Holocaust of World War II. As a medium-sized city in Distrikt Galizien with a large Jewish population, Rohatyn’s German governor created there one of the first of more than 50 wartime ghettos in the region; the Rohatyn ghetto continued to serve the Nazi “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” for nearly two years, until nearly every Jew who had passed through it was dead.

No contemporary official documents defining the Jewish ghetto in Rohatyn have survived, and much of the available unofficial information is either imprecise or conflicts with other records. Because Rohatyn’s wartime Jewish ghetto is an important historical and heritage site in the modern city, this page brings together the available information and analyzes it to determine, as best we can: when the ghetto was created and when it was destroyed; where it was located and the extents of its boundaries; how its boundaries were enforced; and how Jews lived and died there.

The historical information presented here is derived from memoirs by Jewish survivors of the Rohatyn ghetto, Ukrainian witness testimonies, Soviet reports, German aerial photos, plus postwar German and American academic histories. A list of the sources used is included at the bottom of this page.

Ghetto Boundaries During the German Occupation

During the first two years of WWII, Rohatyn along with much of southeastern Poland (former eastern Galicia, today western Ukraine) was occupied by Soviet military and administrative units, and life for Jews in the region was constrained but not mortally dangerous. With the German betrayal of the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa and the invasion of western Soviet-occupied lands, Rohatyn came under Nazi rule in early July 1941, and Jews were threatened with both organized and random murder within days.

Hundreds of Jewish ghettos had been established in German-controlled territories prior to Operation Barbarossa, but in July 1941 the Generalgouverneur in Kraków, Hans Frank, provisionally banned further creation of ghettos in the newly-occupied eastern district, as the Jews in that region were expected to be deported eastward to follow the German advance. [USHMM, p.744, Pohl, p.155]

Establishment of the Rohatyn Ghetto

Despite the ban, in early August 1941 the district governor of Rohatyn (whose seat was in Berezhany), Hans-Adolf Asbach, ordered the Jews of the city to leave their homes and move to a defined section of town. [Pohl, p.155]

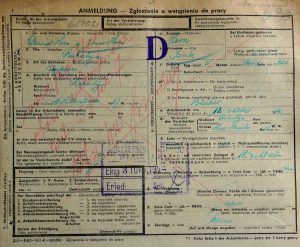

A German labor card permitting 16-year-old Izak (Izio) Horn to work at his family’s bakery from October 1941, producing bread for use outside the ghetto. Source: DAIFO.

Upon the arrival of the German invaders in Rohatyn in 1941, District Commissar Kokhel arrived, who issued several decrees on the subject of Jewish life in Rohatyn. The first order was to separate the Jews from the general population to the so-called Jewish quarter, which occupied the living area – within the streets Rynok, Tserkovna, Ivan Franko, Stalamova, Torgova, Kupeleva[?], and Nove Misto. This entire Jewish quarter was surrounded by the Jews themselves by a fence and was guarded by the local police, Jews could live only in this quarter, but walking around the city was allowed. […] After a while there was an order from Kokhel that all Jews, unlike other nations, had to wear a white armband with a six- pointed star on the left sleeve and an inscription on the armband that read Jude, meaning Jew, and a Jewish Ghetto was formed, and from the Ghetto all Jews were forbidden to go into town, the workers who had to go to work would line up in the morning in a column and go in formation. [Soviet_ESC, Wohl, p.32]

Some survivors remembered the establishment of the ghetto earlier, even in early July, but Asbach did not visit Rohatyn until the 4th of August. [Slovo, issue 5, 06.08.1941, p.2] Prewar non-Jewish residents of the new resettlement area were also forced to move, but were permitted to take the houses of Jews who had previously lived outside the ghetto. Some Jews who already resided within the new ghetto area were permitted to stay in their homes, but the large influx of other Jews forced families as well as strangers to share cramped space in the existing houses. [Glotzer, p.120] Initially the resettled area had the form of a so-called open ghetto, euphemistically called a “Jewish residential district”, meaning in the beginning there was no fence but crossing the boundaries was controlled, first by forcing Jews to wear white armbands with the Star of David, and later forbidding Jews to leave the neighborhood except to work. [Pohl, p.157~158] Ukrainian police helped to enforce the ghetto boundaries, but in general the area within was guarded exclusively by Jewish police. [Pohl, p.243~244]

The ghetto area was strategically chosen for least impact on the non-Jewish population of Rohatyn: The worst section of the city, with its run-down shacks and narrow rooms, was selected. The entire Jewish population (more than 5,000 souls) was forcibly crammed into this area. The entire action was carried out in the span of a day. [Yizkor Book, Wohl, p.306~310; Blech, p.299~305]

Reduction of the Rohatyn Ghetto

The original ghetto area was maintained until after the first major aktion on March 20, 1942. Then the ghetto perimeter was strengthened, and as waves of round-ups, deportations, and killings proceeded through 1942 and early 1943, the area of the ghetto was reduced twice, according to survivors:

On May 1st, 1942, a new Judenrat was formed, the dead members replaced with new ones. The perimeter of the ghetto was reduced, despite the arrival of all the Jews of Knihynicze. […] In January of 1943 the size of the ghetto was further reduced, though it still contained 1000 people. [Yizkor Book, NasHofer, p.287~289]

In the middle of October 1942, the ghetto area was reduced. [Glotzer, p.130]

In the spring of 1942 [after the first major aktion], Jews from Bursztyn, Knihynicze and Bukaczowce entered the ghetto which was narrowed down by then. […] The first half of 1943 was characterized by sporadic killings. In April the wave of executions grew bigger. At the same time, the area of the ghetto was substantially reduced… [Pinkas]

Boundaries of the Rohatyn Ghetto

A wartime street scene at an unknown location in the Rohatyn ghetto.

Source: Katzmann, p.59 (p.33 in the original).

Establishing the historical boundaries of the original and reduced ghetto areas with precision is difficult, but there are clues in a variety of sources. An interwar town planning map from ca. 1932 interpreted in 2010 by survivor Donia Gold Shwarzstein clarifies some street names and town features; a hybrid German street map from 1943 interpreted by Donia and Rosette Faust Halpern identifies additional street names. Boundaries and interior areas defined by named streets or defined roads and which can be identified today include:

- the Rynek (the town square and historical market) [Soviet_ESC, Wohl, p.32]: Ploshcha Roksolany

- ul. Ivan Franko [Soviet_ESC, Wohl, p.32]: at the time, part of the Rynek, today Ploshcha Roksolany

- ul. Cerkiewna/Tserkovna [Soviet_ESC, Wohl, p.32, Glotzer, p.109]: vul. Kotsiubynskoho

- ul. Targowa [Soviet_ESC, Wohl, p.32]: vul. Uhryna-Bezhrishnoho

- ul. Kupelewa [Soviet_ESC, Wohl, p.32]: unnamed spur street off vul. Uhryna-Bezhrishnoho

- ul. Nowe Miasto [Soviet_ESC, Wohl, p.32]: vul. Kudryka; the street name also defined a neighborhood in Rohatyn which extended to the former ul. Nad Rzeką (today vul. Drahomanova), i.e. to the Hnyla Lypa River

- the road to Zaluzhzhia [Pinkas]: vul. Krypiakevycha

Ramshackle buildings with Stars of David in the Rohatyn ghetto.

Source: Katzmann, p.61 (p.36 in the original).

Boundaries defined by other town features which can be identified today include:

- the Hnyla Lypa River [Glotzer, p.109, 120; Yahad, witness YIU/2092U, 1:13:18], and especially the footbridge over the river; there is still a bridge at this location, next to the Holy Spirit Church [Yizkor Book, Wohl, p.306~310; Lederman, p.13]

- the Ukrainian church named for the Birth of the Holy Mother of God at the town square (outside the ghetto) [Yizkor Book, Blech, p.299~305; Glotzer, p.120; Pinkas, Yahad, witness YIU/2092U, 1:13:18; Yahad, witness YIU/2094U, 0:22:21]

- the cross-town creek (Babintsi Creek), which ran next to the road to Zaluzhzhia (today vul. Krypiakevycha) [Trepman, p.106; Yahad, witness YIU/2094U, 22:21; Yahad, witness YIU/2102U, 30:27]

- the new hospital (presumed to be the postwar district hospital, not the prewar Catholic hospital) [Yahad, witness YIU/2092U, 1:13:18]

- the electrical power station [Yahad, witness YIU/2100U, 58:21; Yizkor Book, Blech, p.305]

- the new post office [Yahad, witness YIU/2102U, 30:27]

Other built and landscape features of Rohatyn (including streets) which are described as boundary markers in a variety of survivor and witness testimonies but cannot today be located include:

- ul. Stalamowa [Soviet_ESC, Wohl, p.32]

- the house of Alter Faust [Yizkor Book, Blech, p.299~305; Pinkas]

-

Ghetto buildings burned southwest of the rynok seen in a Luftwaffe 1944 aerial photo. Source: NARA via Dr. Alexander Feller.

the Fischer house (inside the ghetto) and the Fischer store (outside the ghetto) [Yizkor Book, Wohl, p.487~489]

- the printer Skolnick’s house [Arsen, p.190]

- the Feld house [Trepman, p.107]

The Luftwaffe aerial photos of Rohatyn taken on 27 June 1944, a few weeks before the Soviet Army reclaimed the city, can provide strong visual evidence of the location of the Jewish ghetto. The photos were taken a year after the last aktion and the final mass murder of Rohatyn and regional Jews, during which the survivors who were then still in the ghetto described the use of grenades and fire to flush out anyone hiding in houses, attics, barns, and underground bunkers. Many houses and other structures in the ghetto were burned significantly or to their foundations. It is reasonable to assume that only houses in the final, most-reduced ghetto area were targets for destruction in June 1943, so the concentration of burned buildings seen in the photos likely excludes the earlier larger ghetto areas, but there is no separate testimony about this.

Open Questions

It is often not clear whether ghetto boundaries mentioned in survivor and witness testimonies describe the original ghetto area or one of the later reduced areas. One testimony which is clear, however, is from survivor Jack Glotzer, whose family house was on one side of ul. Cerkiewna (today vul. Kotsiubynskoho) before the war and within the ghetto during its initial phase [Glotzer, p.120]; Jack was forced to move with his family in the middle of October 1942 when the ghetto was reduced and their former house was then situated outside the ghetto. [Glotzer, p.130] A reasonable guess is that the prewar Glotzer house was north of ul. Cerkiewna and that the western section of ul. Cerkiewna (closest to the river) became a northern boundary of the ghetto in the October 1942 reduction and resettlement.

The northernmost extent of the original ghetto boundary remains undefined, and we can only speculate based on very limited information. We can suppose that this area was not destroyed by fire during the ghetto liquidation in June 1943, so significant damage would not be visible in the Luftwaffe 1944 aerial photos. We can also guess that only areas with several or many existing houses visible in the aerial photos would have been designated to become a “Jewish residential district” in 1941, as farmland would not be suitable. One Ukrainian witness noted above included the Rohatyn district hospital as a boundary marker, but this may be only approximate, as the hospital did not exist on that site until after the war. There are residential and mixed areas bounded by streets and roads to the north of ul. Cerkiewna / vul. Kotsiubynskoho which are visible in the Luftwaffe 1944 aerial photos and which we can consider reasonable candidates for the northernmost section of the early ghetto area, but even there we can only guess.

A smaller question pertains to the community electrical power station which currently operates in Rohatyn at the same location as before and during the war. It features as a ghetto landmark in one testimony and as a place of work during the German occupation for at least one imprisoned Jewish teenager [Glotzer, p.155] but it is not clear whether the power station was inside or outside the ghetto; i.e. whether the ghetto boundary and fencing was notched to provide access without entering the ghetto. Before and after the war, the power station directors were Jewish [Arsen, p.320], but during the German occupation it was managed by Michael Bilan, a righteous gentile. [Halpern, p.124] It seems improbable that such an important civic utility would be situated inside the ghetto, but we have no information to determine the boundary in this location. It is clear in the Luftwaffe 1944 aerial photo that the power station was not destroyed during the ghetto liquidation.

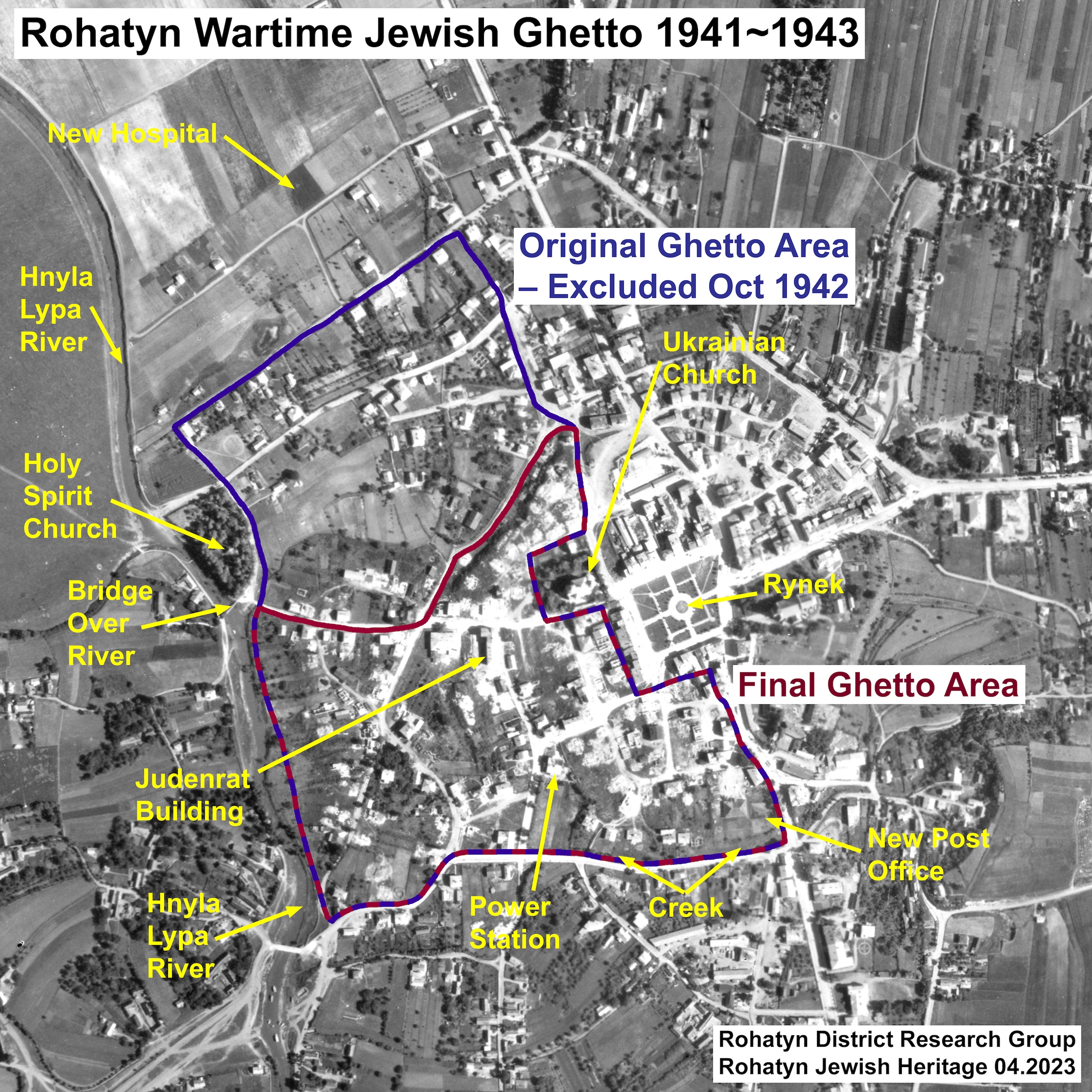

Provisional Maps of the Wartime Ghetto

Two provisional maps are presented here of the Holocaust-era Jewish ghetto in Rohatyn, based on the available information detailed and analyzed above. The first is an interactive map based on Google Maps in an overlay on modern satellite imagery. This map is closely based on an earlier version created by Dr. Alexander Feller in 2018, working from many of the same source materials included above and especially from the Luftwaffe 1944 aerial photos. In the map below (which can be zoomed and panned directly on this page or in a larger version by clicking the icon at the right of the header), the red area represents our understanding of the boundaries of the final, reduced Jewish ghetto area, circa June 1943 when the ghetto was liquidated. Our best guess of the boundaries of the original, larger ghetto established in August 1941 includes both this red area and the blue area to the north, which we suppose was the section excluded from the ghetto in ordered reductions between late 1942 and early 1943. Most of the modern street names interpreted from survivor and witness testimonies can be read in the annotations on this map.

The second map is a static image excerpted from one of the Luftwaffe 1944 aerial photos, with these same provisional boundaries indicated in overlay using the same color scheme (the final ghetto outline in red, the original ghetto outline in blue and red). Several of the buildings and landscape features described as ghetto boundary or interior landmarks by survivors and witnesses are also shown on this image.

Life in the Ghetto

Although the boundary locations of the Rohatyn Jewish ghetto were not well documented during the German occupation or after, the evolving and increasingly horrible experience of life in the ghetto was described by every Jew who was imprisoned there but somehow survived, in a number of memoirs, video and audio testimonies, poems, and more. Both the variety and the terror inherent in their experiences is almost incomprehensible now; it is no wonder that some were driven to madness.

Rohatyn Judenrat members with armbands in autumn 1941. Shlomo Amarant (center right) was head of the Judenrat for a while; Meyer Weissbraun (center left) was head of the Jewish ghetto police. Source: Schnytzer-Wald Family Collection.

Despite ever-worsening living conditions imposed by the German authorities, Jews in the Rohatyn ghetto attempted to survive through both individual and organized efforts. As in many Nazi ghettos across Europe, the Rohatyn prisoners were required to establish a kind of council, the Judenrat, and an unarmed police force; these were intended by the Germans to simplify enactment of their decrees affecting the Jews and to minimize interactions between Germans and Jews overall, but the ghetto inmates also attempted to use these administrative bodies to relieve some of the heavy tolls they were required to pay. An academic study which surveys the Jewish ghetto experience through the war years and focusing significantly on Poland is edited by Eric J. Sterling, Life in the Ghettos During the Holocaust (see the Sources); the Rohatyn ghetto fits within this context, but no single text can capture the full experience of even one ghetto.

Many of the Rohatyn memoirs are available only in book form, but some important documents with vivid descriptions of ghetto experiences are also available online, such as the Rohatyn Yizkor (Memory) Book (see especially “How Rohatyn Died” by Dr. Abraham Sterzer) and Jack Glotzer’s memoir I Survived the Holocaust Against All Odds (see the Sources). Borys Arsen’s remarks at the top of this page echoed Dr. Sterzer’s earlier chilling synopsis:

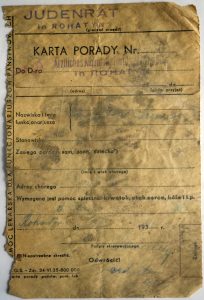

A prewar card repurposed by the Judenrat in Rohatyn, found in the walls of the building in 2011. Original card preserved by the Rohatyn Opillya Museum.

The Judenrat that was formed was supposed to represent the Jews towards the local authorities and the Gestapo in Stanislawow, and later in Tarnopol. It also had the task of moving the Jews into the ghetto. The Judenrat was also responsible for quiet in the ghetto, the carrying out of fines and contributions and other orders. […] The entrances to the ghetto were closed by gates, guarded by Jewish policemen. […] In some of the actions and in the final liquidation the first to be shot were the Jewish police. […] The ghetto wasn’t able to absorb all the Jews of Rohatyn. Two families had to squeeze into each room. No one even spoke of a kitchen or other amenities. There was no place to put furniture, so they were left in the former homes, outside the ghetto. Jews were happy to find a corner for themselves and their children. This crowdedness led to extremely unsanitary conditions. […] The ghetto became even more crowded when the Jews from the nearby villages were also forced in. […] There was hunger in the ghetto from the very first months. Not all the Jews had something to sell. […] Whatever little the Jews had had been taken by the Germans as obligatory contributions. […] The Jews were ready to do anything to save themselves from starvation and to give their children a bit of food. On the streets of the ghetto you could already see people swollen by hunger, and sick people, their faces dark as the earth. Despite this, we had to go to our work outside the ghetto – in the offices, stores, roads and the railroad. The sick and hungry didn’t receive either food or money for their work. People dreamed of a piece of bread or of a potato. […]

The lack of food and the unsanitary living conditions and crowdedness made the ghetto prey to terrible sicknesses, especially dysentery and typhus. Lice flourished and filed the beds, the tables, and even the sidewalks. There wasn’t any soap, nor any possibility to wash clothes or oneself. The inhabitants of the ghetto fell like flies. And there wasn’t any help. The pharmacists on the Aryan side refused to sell the Jews any medicines. The cemetery soon began to fill up. Jews died without count and without statistics. Weak by nature, they weren’t sick for a long time. After two or three days of illness they just died. Wagon-fulls were carried to the cemetery every day. People died without being wept over and mourned. It was hard to know what was preferable — to continue to live and suffer or the sooner the better to make an end of all the troubles. The typhus epidemic reached its climax in the winter of 1942~43. At the demands of the authorities the Judenrat opened a hospital with a limited number of beds, where the homeless and poor sick were brought. At one time, when the hospital was full, a Viennese Gestapo-man, Hermann, entered the hospital, assembled the doctors, other workers, and the nurses, shot the patients in their beds and then the personnel. Then he ordered the Judenrat to clear away the dead bodies and to open the hospital again. [Yizkor Book, Sterzer, p.440~442]

German photographs of the Rohatyn ghetto after the liquidation, showing bunkers opened outside and inside. Source: Katzmann, p.61 & 66 (p.36 & 41 in the original).

After the spring 1942 aktion, all of the survivors describe the attempts by Jews in the ghetto to evade the incessant raids and round-ups for deportation or execution, through the creation of secure hiding places in closets, building attics, under floors, and dugout shelters deeper in the soil. These hideouts were all called “bunkers”, but the ones dug deep under houses and other buildings were remembered most vividly by those whose lives were temporarily saved there. Three of the largest and best fortified bunkers were named for places of German military defeat and Soviet resistance in the east: Stalingrad, Sevastopol, and Leningrad. [Katzmann, p.149 (p.34 in the original); Kimel, p.40~41] The bunkers were imperfect protection at best, and only for some, creating lethal risks for others:

The experience of the first aktion showed that elderly people in such unusual conditions start to cough and sneeze, and children start to cry. Old people were gagged and suffocated, and children were often given such a dose of sleeping pills that they did not wake up after it. There were rare cases when all sedatives did not help, the unfortunate were simply suffocated. [Arsen, p.188]

As life became deadlier and deadlier in the ghetto, any available energy was focused on food, health, and self-protection, though all of these were too scarce for most prisoners. Able-bodied teenage and adult Jews who could stand heavy forced physical work survived better for a while than the very young and the elderly, because workers were sometimes given more food on external job sites to sustain their labor. [Arsen, p.164 & 167; Glotzer, p.127]

The desperate situation in the ghetto led to occasions of panic, hysteria, depression, and worse, but for some it also heightened the will to live and even strengthened resilience:

Despite all the tragedies, pain, and hopelessness, there was only one case of suicide. This was less than in normal times. It looks as if living in dangerous conditions has a therapeutic value. As it is written in the Talmud, “Sakanath Nefesh Doche Hakol.” The danger of life overrides all other problems. […] In between the spurts of danger, young people fell in love, women became pregnant, quarrels erupted between neighbors, and so on. Even parties were given in the ghetto. [Kimel, p.36~37]

Alexander Kimel recorded that only some of the ghetto inmates lost their faith during their ordeal:

Despite the hunger, persecution, and death, many Jews maintained their religious observances. Torah scrolls were distributed among private homes, and people congregated during the day to say Kaddish (prayers for the dead) for those who had died. [USHMM, p.822]

Kimel also noted some lighter aspects of life in the Rohatyn ghetto:

The ghetto was full of rumors. We used to joke that the ghetto was running its own news service, called Jidden Willen Azoj (JIWO, “Jews Wish So”). The Germans confiscated all of the radios, so without newspapers it was easy to float rumors. […] Another favorite pastime in the ghetto was devising a creative punishment for Hitler. The most favorite variant: Hitler would be caught, put into a mobile cage, and transported from town to town so that each Jew could spit into his face. [Kimel, p.36~39]

Ultimately, though, every experience of life in the ghetto turned toward the tragic:

One day I was invited to a violin concert in the ghetto. It was an event I will never forget. In a small dark room, about fifteen teenagers gathered to listen to a violin recital by one of our friends. I looked at those emaciated faces, wrinkled with pain, the downcast eyes revealing the distress of their souls. […] The violinist played cheerful Russian songs […] and suddenly he switched the tune, and the known melody of the “Hatikvah” filled the room: “Od Lo Avda Tikvatenu” – our hopes are still alive. The tune and the words brought me to tears. I stood up, and through tears I looked at the beautiful youth condemned to death and asked myself a question: “Why? Why is this happening to us?” [Kimel, p.39]

Death in the Ghetto

Altman family portrait, about 1938. Seated are Malkah and Max; standing left to right: their children Josie, Clara, and Izie. Malkah and Clara hid with other women and children in a cellar during the December 1942 aktion, but were discovered and died either in Rohatyn or at Bełżec. Source: Glotzer-Barban Family Collection.

Once the Nazis decided not to deport Jews eastward from Distrikt Galizien, the ghettos increasingly became killing machines, relentless in destroying all Jews in the region. The modes and methods of killing were various and fluid, adapting to local conditions and to competition between German authorities for power and prestige. In Rohatyn, the intense 20 March 1942 aktion apparently took place earlier than originally planned because the German district SS-Hauptsturmführer in Stanisławów, Hans Krüger, chose not to wait for deportation trains to the death camp near Bełżec and instead organized a mass murder at a brickyard beyond the train station, less than two weeks before control of Rohatyn was to pass to the Sipo-Aussendienststelle in Tarnopol, headed by SS- Sturmbannführer Hermann Müller. Müller himself was replaced by SS-Hauptsturmführer Wilhelm Krüger in June 1943, just before the Rohatyn ghetto liquidation. [USHMM, p.821; Pohl, p.190]

Both of the mass round-up and killing events in Rohatyn were initiated by hundreds of shootings in the ghetto itself, by deadly beatings and further shootings in the town square, and still more shootings during the forced march of the victims toward the pits which became their graves. In all, between 8,000 and 12,000 Jews died in Rohatyn during the two largest aktions of March 1942 and June 1943. Thousands of Jews also died as a result of Rohatyn ghetto round-ups preceding the carefully-organized district deportations to the death camp near Bełżec. On 21 September 1942, a ghetto roundup under heavy Gestapo control resulted in the death by shooting in Rohatyn of 300 or more Jews, plus the deportation and then lethal gassing of at least 800 more Jews at Bełżec. [Glotzer p.128~129; USHMM p.821] That scene was repeated on 08 December 1942, when 500 Jews were shot to death in Rohatyn and another roughly 1400 were deported and gassed to death at Bełżec. [Glotzer p.130~131; USHMM p.821~822]

In between these major events, there were frequent incidents which resulted in the beating or shooting deaths of individual or smaller groups of Jews. Almost any German order could result in killing: a demand for slave workers or money; the creation of a ghetto hospital or its destruction; the discovery of a Jew working outside the ghetto without an armband – anything, no matter how trivial, to demonstrate Nazi mastery and cruelty. [Kimel, p.36 & p.41; Trepman, p.106; USHMM, p.822] However, these incidents played out against a backdrop of constant, grinding death from intentional starvation and disease, leading to waves of burials in the Jewish cemeteries. All of the survivors’ memoirs reflected on this later:

Jews suffered from hunger in the ghetto starting from the first month. The Germans forbade the peasants to supply food to the Jews in the ghetto. You could see on the streets in the ghetto people swollen from hunger. [Glotzer, p.120~121]

Epidemic typhus, spread in the Rohatyn ghetto by body lice due to severe overcrowding and the lack of adequate sanitation and medications, killed a great many weakened individuals (again, the very young and the elderly), and incapacitated otherwise stronger Jews with fevers, nausea, confusion, unconsciousness, and many other complications. [Glotzer, p.127 and p.130]

Although very few Jews who had survived nearly two years in the Rohatyn ghetto made it through the final destruction and mass killing in June 1943, some of those who perished in the liquidation did not die without a fierce fight in the bunkers, and some may still lie where they fell in the ghetto:

An entrance to a bunker, dug out by the Germans to flush out hiding Jews with fire. Afterward, this place may have served as a grave. Source: Katzmann, p.63 (p.38 in the original).

Overall, the resistance of the Jews in Eastern Galicia was comparatively weak. The Jews of eastern Poland had the Nazi mass murders in mind from the very beginning. Since autumn 1942 at the latest, it was clear to them that the total extermination of all Jews was imminent. Nevertheless, it took until April 1943 – 18 months after the beginning of the massacres – before armed resistance flared up. During the liquidation of the ghettos in Brody, Lviv, Jaworow, Brzezany, Buczacz, Borszczow, Horodenka and Rohatyn, there were minor battles. [Pohl, p.369]

Now that the ghetto was destroyed, through Katzmann the Germans and their accomplices had orders to kill any Jew found alive, including those pulled from underground bunkers where the ghetto had been. In one contemporary German report:

A few days after the last action in Rohatyn, I saw 6 – 8 Jews – there was also a small child of about 4 years among them – shot by two gendarmes. Two other gendarmes who were standing by handed the two shooters either the rifles or the ammunition. I heard the little child say to his mother before the shooting: “Mommy, mommy, give them money.” The bodies of these 6 – 8 Jews were not buried, but simply thrown into bunker holes. [Pohl, p.365]

Sources

Arsen: Borys S. Arsen; My Bitter Truth – I and the Holocaust in Prykarpattia; Nadvirnianska Drukarnia; 2004.

Glotzer: Jack Glotzer; I Survived the Holocaust Against All Odds: A Unique and Unforgettable Story of a Struggle for Life; bilingual edition; Kyiv: Ukrainian Center for Holocaust Studies, Library of Holocaust Memoirs, 2022.

Halpern: Rosette Faust Halpern; A Journey Through Grief – The Autobiography of a Holocaust Survivor; lulu.com; 2013.

Katzmann: Friedrich Katzmann, Rozwiązanie kwestii żydowskiej w Galicji (Lösung Der Judenfrage Im Distrikt Galizien); Seria „Dokumenty”: tom 5; Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, Warszawa; 2001.

Kimel: Alexander Kimel; “Autobiographical Notes”; in: Eric J. Sterling, ed., Life in the Ghettos During the Holocaust; Syracuse University Press; New York, 2005.

Lederman: Sylvia Lederman; Sheva’s Promise – Chronicle of Escape from a Nazi Ghetto; Syracuse University Press; New York, 2013.

Luftwaffe: Image series GX-1404, exposure 5; NARA Records Group 373, archive number 306065, German Flown Aerial Photography, 1939~1945; image accessed by Dr. Alexander Feller, 2009.

Pinkas: Encyclopedia of the Jewish Communities of Poland (Pinkas ha-kehillot Polin), Volume II (Eastern Galicia); eds. Danuta Dabrowska, Abraham Wein, Aharon Weiss; by Zvi Avital, Danuta Dabrowska, Abraham Wein, Aharon Weiss, Aharon Jakubowicz; Yad Vashem, Jerusalem 1980 (in Hebrew). Online English version hosted by JewishGen. Pages 506~510 on Rohatyn coordinated by Alex Feller, English translation by Ruth Yoseffa Erez.

Pohl: Dieter Pohl; Nationalsozialistische Judenverfolgung in Ostgalizien 1941-1944: Organisation und Durchführung eines staatlichen Massenverbrechens; 2. Auflage; Studien zur Zeitgeschichte, Herausgegeben vom Institut für Zeitgeschichte Band 50; München; 1997.

Slovo: Рогатинське слово (Rohatyn Word); periodical (mostly weekly) in Ukrainian language published in Rohatyn under German occupation; 23Jul1941~03Dec1941; sourced from Libraria Ukrainian Online Periodicals Archive.

Soviet_ESC: Soviet Extraordinary State Commission Report; Investigation of Atrocities by the German Fascists and Their Accomplices in the Rohatyn District of Stanislaviv Oblast; State Archive of the Russian Federation R-7021- 73-13; 1945.

Trepman: Paul Trepman; Among Men and Beasts; translated from the Yiddish by Shoshana Perla and Gertrude Hirschler; A. S. Barnes and Co., Inc.; Cranbury, New Jersey, 1978.

USHMM: Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945; Vol. II: Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe; Martin Dean and Mel Hecker, eds.; United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and Indiana University Press; Bloomington, 2012.

Yahad: Yahad – In Unum Interviews with Rohatyn Holocaust Witnesses; transcription and translation by Rohatyn Jewish Heritage; 2016/2018.

Yizkor Book: Donia Gold Shwarzstein; Remembering Rohatyn and Its Environs; Meyer Shwarzstein, publisher; 2019. See also two online versions: an earlier English translation in text form, and images of the original book with Hebrew, Yiddish, and English sections.