![]() Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Paul Trepman; Among Men and Beasts; translated from the Yiddish by Shoshana Perla and Gertrude Hirschler; A. S. Barnes and Co., Inc.; Cranbury, New Jersey, 1978.

Introduction

This page describes the English translation of a memoir by Paul Trepman (1916 – 1987) about his experiences during World War II in Poland, called “Among Men and Beasts”, published in 1978 from an original Yiddish manuscript based on newspaper articles he had written mostly between 1947 and 1953. The memoir spans the entire European war, from the summer of 1939 until the day of Germany’s surrender in 1945. In those several years, Trepman experienced life under Soviet and German occupation in Galicia and Warsaw, took on a false identity as an ethnic Pole, worked as an intermediary between Jews in the ghettos and others to finance resistance efforts, and struggled to evade capture while moving about the region. For a time he worked in the Rohatyn ghetto; he was present in Rohatyn during the final ghetto liquidation in June 1943. Trepman was arrested as a Pole and held in the Stanisławów Gestapo prison, then transferred to the Majdanek concentration camp, the first of six he survived until liberation – still posing as an ethnic Pole.

The book is out of print now but still available in libraries; good-quality new old stock and used copies are also readily available from independent booksellers.

This page also includes a brief summary of Trepman’s life during and after the war, plus several details from the memoir with particular value for researchers of Rohatyn’s history. These notes include material sourced by Rohatyn Jewish descendant Ruth Erez and Israeli historian Dr. Eran Zohar, as well as other material from the memoir of Trepman’s wife Babey Widutschinsky-Trepman, plus from Yad Vashem and the Jewish Virtual Library. We especially want to thank Elly Trepman (Paul’s son) for his review of this article and his corrections and additions to this material, which add details not available from any other sources; Elly is also currently working to get the original Yiddish version of the book into print.

A Brief Summary of the Author’s Life

Trepman (top row, third from right) with other members of Betar, 1930s.

Source: Trepman Family Collection.

When the first bombs fell on Warsaw on 01 September 1939, Pinkas (Paweł, or Paul) Trepman was a 22-year-old Jewish university student, teacher, and member of the Zionist Revisionist movement in Warsaw. He was living at his mother’s home in Warsaw at the time, on leave from Stefan Batory University in Vilna; a few days later he and several Jewish friends fled east among large crowds of refugees. For the next few weeks he traveled on foot, on a Polish tank, on horse-drawn carts, on major and minor roads, under daily German bombing, to Kovel in what soon became the “Russian sector” of Poland, and then by train via Lwów to Zabolotiv (southeast of Kolomyia), a journey of some 800km.

Trepman spent a year teaching at a Communist-administered Jewish school in Zabolotiv, then was discharged because of his past Zionist associations; he applied to teach at a Ukrainian school in Burshtyn but was sent to Rohatyn and then on to the small Ukrainian village of Klishchivna, 10km north of Rohatyn, where he was forced by the Soviets “to disseminate Communist culture” against his will for six months. He then was granted a transfer to teach in the small Polish weavers’ village of Ludwikówka near Burshtyn, where he stayed for some months before he moved back to Zablotiv, in time to see the departure of the Soviets and the arrival of the first German military engineering unit. In December of 1941, Zablotiv suffered its first major pogrom, and 600 Jews were killed; living conditions became terrible for the remaining Jews, who were also forbidden to travel. Trepman engaged in black market trading of saccharine to earn money. Several weeks later, with the help of a local friend and a priest in a nearby town, he acquired the identity papers of a deceased Polish man and walked to Kolomyia, where he took a train to Warsaw.

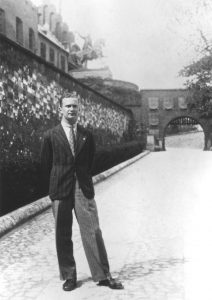

Trepman (with camera at left) photographing Ze’ev Jabotinsky at Warsaw’s Okęcie airport in 1937. Source: Jewish Public Library (Paul Trepman Collection) and Jabotinsky Institute.

From March to July 1942, Trepman smuggled into the Warsaw Jewish ghetto on several occasions to visit his mother. He was trapped in the ghetto when it was sealed at the start of the Grossaktion Warsaw in July 1942, but with the help of a friend was able to exit the ghetto on a work detail to an SS estate at Falenty, about 15km southwest of the ghetto. Through a Polish woman he met there, he escaped from Falenty, made his way back to Warsaw, and accepted an invitation from the Polish “People’s Army” (Armia Ludowa, AL), a Communist-leaning branch of the underground resistance, to join their workers using a new Aryan Polish identity (as “Paweł Kołodziejczyk”). He worked for several months undercover for the AL on a farm in Drzewce, 25km northwest of Lublin. The AL then sent him on to Lwów with the task of buying silver from Jews for use as currency to purchase ammunition to help arm the underground resistance.

At the beginning of 1943, Trepman traveled from Lwów to Burshtyn, where he was still too well known to protect his true identity, so he quickly moved to Rohatyn. Because of earlier aktions there, the majority of Rohatyn’s Jews had already been killed; by then three quarters of the ghetto residents were from neighboring towns and villages, so his odds of being recognized were low. Through a few old friends he solidified his new identity and met with local Jewish leaders, including the chief of the Jewish police, Meir Weisbrojn, and his wife Clara. The ghetto was still closed only by regulation, not by physical fencing.

Clara Weisbrojn’s Slavic features and her ability to speak Polish and Ukrainian with a native accent prompted her husband to try to send her to Warsaw to live as an Aryan, as he did not expect to survive the war himself. In mid-February, Trepman escorted Clara by train via Lwów to Warsaw, but they were recognized as Jews by local authorities and were blackmailed to prevent arrest; both had to return to Rohatyn shortly after.

Trepman continued his silver-smuggling activity for the AL, climbing the ghetto fence with purchased items, storing them at a local Polish man’s house, then forwarding the pieces to a contact in Lwów; sometimes Trepman carried the pieces himself to the contact, who also gave him news and instructions from the Polish underground in Warsaw. In the meantime, Jews in the Rohatyn ghetto had heard news of the Warsaw ghetto uprising, and under leadership of Meir Weisbrojn, began to prepare a huge underground bunker for 300 people in the forest some 10km outside of Rohatyn, a treacherous affair of logistics and hard labor that ultimately went unused because the bunker was discovered by an outsider.

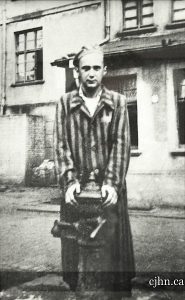

Trepman two to three weeks after the liberation of

Bergen-Belsen. Source: CJHN.

In time Trepman was entrusted with leadership of a second Jewish partisan unit in Rohatyn, and he traveled the district to exchange gold, silver, or cash for weapons, while both partisan units prepared to leave the ghetto to join larger underground forces. In the midst of this preparation came the violent Rohatyn ghetto liquidation of June 1943, which Trepman survived within the ghetto by hiding, crammed into a cellar with seven other Jews. After more than a dozen hours barely breathing, German officers broke open the cellar trapdoor and pulled the people out. Trepman was saved from the other Jews’ fate by his Polish ID and a Russian compass in his pocket; he did not see the others’ deaths on the following days.

Trepman was held as a Polish political enemy of the Nazi regime and forced to work for three months in the Stanisławów Gestapo prison, suspected of having Communist sympathies; during this time he was also interrogated by the Gestapo under torture, and was placed in solitary confinement. In August he was transported via Lwów to the Majdanek concentration camp outside Lublin, and became a slave laborer. There he witnessed the segregation of around 20,000 imprisoned Jews for execution on a single day, part of the SS-directed “Operation Harvest Festival” in the General Government; for a while after he was one of the few Jews in the camp (still under cover as an Aryan Pole).

Trepman (second from right in the front row) with fellow members of the Central Committee of the Liberated Jews in the British Zone at

the Bergen-Belsen DP camp after the war.

Source: Yad Vashem.

As the Red Army pushed the Wehrmacht further west toward the end of the war, prison camps were evacuated and obscured by the Germans, and prisoners were killed or transferred again and again. Trepman himself was transferred from Majdanek to Gross-Rosen, Sachsenhausen, Retzow, Ellrich, and finally Bergen-Belsen. He endured relentless starvation, dehydration, lice, filth, disease, and mental and physical abuse, while thousands of others around him died slowly or brutally. After more than a year and a half of his nightmarish camp life, in April 1945 most of the German guards at Bergen-Belsen destroyed administrative files and left, and days later the British army liberated the camp where several tens of thousands of prisoners barely clung to life, Trepman among them.

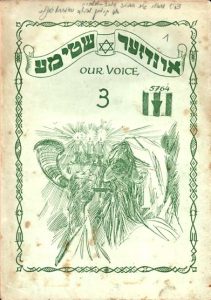

Issue 3 of Unzer Sztyme. Source: Yad Vashem.

Finally, after liberation, Trepman resumed his Jewish identity. He began to contribute to cultural activities in the Bergen-Belsen Displaced Persons camp, and in July 1945 he became a founding coeditor (with Rafael Olewsky and David Rosenthal) of Unzer Sztyme, the first regularly published Jewish newspaper in the British Zone of Occupation. Working as a journalist, he covered the Nürnberg military war crimes trials. In March 1946, he married a Lithuanian Jewish survivor of the Bergen-Belsen camp, and in 1948 the couple emigrated to Montreal, Canada, where they raised a family and taught in Yiddish and Hebrew schools; Trepman also served as executive director of the Jewish Public Library there.

Trepman with microphone at the dedication of the DP camp memorial at Bergen-Belsen. Source: USHMM.

Trepman was active in the survivor community, both in Germany and in Montreal; he organized and attended memorial events at the camp site in the immediate post-war years. He also established a Montreal chapter of Bergen-Belsen survivors, and served as its president. He was a prominent Yiddish writer in Canada, producing newspaper articles for the Keneder Adler under his own name and under pen names, plus several books about his personal experiences and on a variety of other topics. He died in 1987.

As noted, Trepman’s memoir was originally completed in Yiddish around 1978, from earlier newspaper articles. A Hebrew version with some slight differences in the text is archived at the Jabotinsky Institute in Tel Aviv, among other papers relating to the Warsaw ghetto. Along with a chronology of Trepman’s life during the war, the memoir includes numerous character sketches of people he met through those years, including officials and ordinary people of all ethnic groups, and both adults and children. The book ends with a written “gallery” of what he calls “Holocaust portraits”, an additional eleven studies of people he had met or had heard about and whose lives were upended by the war, including Janusz Korczak and Mordechai Anielewicz, respectively the head teacher and the leader of the Jewish resistance in the Warsaw ghetto. The book closes with entries in a diary he began two days before the liberation of Bergen-Belsen, and his reflections on his life as a Jew masquerading as an Aryan Pole.

Elements of the Memoir with Significant Value to Rohatyn Studies

Warsaw understandably occupies a significant part of Trepman’s memoir: the Polish capital had been his home before the war, and he entered the Jewish ghetto there under German occupation several times in 1942; many of the character sketches in the memoir highlight the effects of ghetto conditions on the people of Warsaw, ranging from militancy to madness. Likewise, the intense stress of prison and camp life which he endured for almost two years during the war also makes up a significant portion of the memoir.

Trepman’s decision to move to Rohatyn in early 1943 for what would be only a few months coincided with a determined shift on the part of some in the ghetto there to active defense, and he observed or participated in many aspects of the last days of the local Jewish community. In addition, his singular position as a Jew in Polish disguise gave him a perspective on ghetto conditions from both sides of its perimeter. Thus his relatively brief time in Rohatyn produced some important memories of people and events, many of which are unique in the survivor literature from the town.

In particular, the detail he provides about the development of Jewish armed resistance and defensive bunkers both in and outside the ghetto is rare, and was apparently unknown to most other Rohatyn survivors (who were aware of household hiding places but not organized and armed group bunkers). To the personal stories of betrayal and salvation told by other Rohatyn memoirists, Trepman adds new instances of German, Polish, and Ukrainian torment (including individual names), as well as reliable Polish and Ukrainian helpers, described though not often named. Researchers studying the histories of Rohatyn Jewish families will recognize many names, including Weissbraun (Weisbrojn in the memoir), Wald, Feld, and others. In the “gallery of Holocaust portraits” which concludes the book is a story Trepman must have heard from ghetto inhabitants about a Jewish man from near Burshtyn who wound up in the Rohatyn ghetto, and the Ukrainian girl who followed him there out of love, ultimately ending in a mass grave with him and his family among the Jews of Rohatyn.

Additional References

Howard Roiter with Paul Trepman; Paul Trepman interviewed by Howard Roiter on his experiences during the Holocaust (audio); Montreal, May 1975; Internet Archive, segments 464B and 465.

“Maidanek – The Chimney is Your Destruction”; in: Voices From the Holocaust; Howard Roiter; William-Frederick Press; New York, 1975; p. 181-213.

Paul Trepman; Interviews (audio and video); Paul Trepman Collection; Jewish Public Library Archives; Montreal, 1986 and 1987.

This page is part of a series on memoirs of Jewish life in Rohatyn, a component of our history of the Jewish community of Rohatyn.