![]() Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

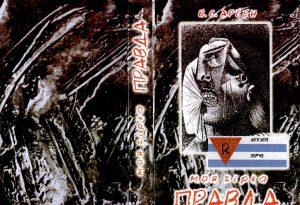

Borys S. Arsen; My Bitter Truth – I and the Holocaust in Prykarpattia; Nadvirnianska Drukarnia; 2004.

Introduction

A strange property of human memory: I can forget what my wife Olena Mykhailivna treated me to yesterday, but the experienced events of sixty years ago, as if they were yesterday, appeared in every detail before my eyes today and begged to be written on these pages of memory.

The memoir of Borys Arsen (born Borys Akselrad) is unusual in several ways among Jewish personal histories of the Holocaust in the Rohatyn area. Arsen grew up on farms in villages near Rohatyn, and he knew both rural and urban life in the district. He survived not only the Rohatyn ghetto, but also the Gestapo prison in Ternopil, the German concentration and extermination camp of Auschwitz II-Birkenau in Poland, and the forced-labor concentration camp of Buchenwald in Germany (see Paul Trepman’s Among Men and Beasts for a parallel story). Like many other survivors, the author owed his life to the actions of a small number of righteous gentiles; Arsen is one of the few Jews from the Rohatyn area who successfully applied for recognition of his savior on Yad Vashem’s Walls of Honor on the Mount of Remembrance, and the only one whose savior was killed in part for his rescue actions. Unlike almost all other Jewish survivors, Arsen remained in western Ukraine after the war ended and to the end of his life; while a few other Jews stayed in the region of “Prykarpattia” (the Ukrainian Carpathian mountains and their foothills in the Ivano-Frankivsk, Lviv, Chernivtsi, and Zakarpattia oblasts today, bridging southeastern Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Romania during the interwar period), we are not aware of any others who published their experiences from before, during, and after the war.

In addition to telling Arsen’s own personal history, the memoir incorporates several chapters which together give an overview of the history of the region and its demographics, including the villages, towns, and cities where he lived as well as other significant places in western Ukraine which he studied. His research was especially thorough on the events, people, and effects of the Holocaust, with particular emphasis on regional causes of the destruction of Galician Jewry, making it one of the first published studies by a local witness and historian not long after Ukraine gained independence.

Because this memoir was written in Ukrainian and published in print form only in western Ukraine, the book is not well-known in the Jewish survivor and diaspora communities in other countries abroad. With this summary we aim to introduce the memoir to more readers, and hopefully to inspire others to use it for their own historical research on the Holocaust in Rohatyn and its region. Rohatyn Jewish Heritage thanks the Rohatyn city library for donating to us the copy of Arsen’s memoir which we read to make this summary.

Organization of the Memoir

The text is divided into 32 chapters plus a preface and an afterword, with photographs and other illustrations inserted throughout, plus 25 pages of color and black and white photos at the end. As noted above, the material is roughly organized into three types of chapters, covering: the author’s life before, during, and after the Holocaust; regional history and demographics; historical information about the Holocaust, especially in what had been southeastern Poland – today western Ukraine. Arsen’s personal history is organized chronologically, with other material interspersed in the text in separate thematic chapters. A number of chapters include some aspects of all three types of history.

The chapters are grouped here by type, with their original numbering:

Arsen’s Personal History

Preface

1. Where Do I Come From?

2. The Village of Chesnyky

3. On an Independent Path of Life

4. That’s How it All Began

8. On the Eve of and in the First Days of the Nazi Occupation

12. Daily Life in the Rohatyn Ghetto

13. Life in the Ghetto After the First Action in Rohatyn

14. I’m at Work

15. Under Another Name

21. Life Goes On

22. Echoes of Stalingrad

23. A Visit from My “Father”

24. In the Ternopil Prison

25. As “Guests” in Birkenau

26. In Buchenwald and its Commands

28. At Will and Freedom

29. On the Soviet Convoy

30. In the Motherland

31. In Ivano-Frankivsk

Regional History and Demographics (Rohatyn District and Beyond)

5. Briefly about Rohatyn and the Rohatyn District

6. The History of Jewish Settlement in the Rohatyn Area

7. What Should Not be Forgotten

Holocaust History (General and Regional)

9. How it Started and What Happened in Stanislaviv

10. The City of Nadvirna

11. How the Jewish Community in Kolomyia was Destroyed

16. How Jewish Rohatyn Died

17. How and When did the Rest of the Jews of Prykarpattia Die?

18. What Do the Numbers Say?

19. The Holocaust and the Ukrainian Police

20. The Holocaust and the Church

27. For the Memory of Future People

32. Only We are Left Alive Here!

Afterword

A Brief Summary of the Author’s Life

Before the War

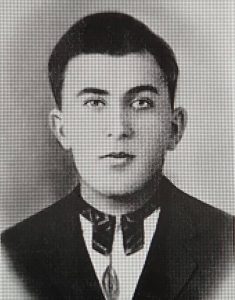

Borys Akselrad was born in late 1921 in the village of Chesnyky, about 10km east of Rohatyn, so that his mother Miriam could be aided in the birth by a midwife from her family there. Borys’s father Shimon-Chaim was from the village of Pidkamin, about 10km northwest of Rohatyn, and the family lived on their own farm there not far from the families of Shimon-Chaim’s siblings, who also farmed. The Akselrads were Orthodox Jews living in good relations with their Polish and Ukrainian farming neighbors; other Jews in Pidkamin engaged in crafts and small trade. In the interwar years, the Jewish community of Pidkamin maintained a synagogue with the functions of rabbi fulfilled by the best-educated members in rotation, and a cheder run by a melamed under contract. The synagogue also served as a community meeting house for public announcements and decisions, sometimes bringing a respected rabbi from Rohatyn to help resolve more complex issues.

The author emphasizes in his memoir that he witnessed no inter-ethnic or inter-faith conflicts at all in Pidkamin until 1939. From age 6 (after studying at the cheder for a year) he attended classes conducted in Polish, with Ukrainian language and literature classes twice per week, at the five-grade school in the village. Jewish children were exempt from catechism classes on Fridays, but Borys often stayed out of curiosity to observe the Greek Catholic classes, and in so doing learned some basic prayers which helped to strengthen his false identity during the later German occupation.

In 1931, his father’s mother died, and with her the management of the family’s farms was divided, leaving Borys’s family with less income. That same year Borys was admitted to first-year classes at the Piotr Skarga gymnasium (the Polish “Red School”) in Rohatyn, and was given room and board in the city. The cost of the school and his housing were steep for the family, but less than if he had attended the Ukrainian gymnasium; the family believed that after investing in Borys at the gymnasium he would take professional employment somewhere, so his future farm inheritance and income was split among Borys’s siblings.

Political changes in Poland under the final years of Piłsudski‘s rule and the “Endek” government which followed made school and life difficult for Jewish and Ukrainian students in Polish-run schools, but Borys avoided much of the trouble by maintaining good grades.

Around 1935, the Akselrads sold their farm in Pidkamin and bought a large parcel of mostly virgin land and forests but without water about 3km from Chesnyky, near Borys’s mother’s family. Slowly the Akselrads, especially 50-year-old Shimon-Chaim, prepared the land for crops, built rough housing, and carried water from a spring for farm and household use. Borys walked via Pukiv to Rohatyn for school on Monday mornings, and sold oil from the farm there during the week; his mother walked to Rohatyn to sell butter and cheese, bringing specialty breads home to the family. The family’s Orthodox religious life partially collapsed under the strain of building a home and farm, but Borys’s father continued to observe shabbat and to attend prayers, and he attached mezuzahs to the door frames and Keren Kayemet charity boxes for Mandatory Palestine. Borys learned to balance heavy physical work on the farm with heavy study at school, even in an environment of rising inter-ethnic and especially political tension.

According to the memoir, the interwar period in Chesnyky was strongly influenced by socialist activism, political self-education, and anti-government peasant organizations, with workers’ strikes and sometimes violent responses; Borys participated in meetings and read the political literature available to him. By 1938 the Akselrad family recognized that changes in Poland and elsewhere in Europe significantly darkened their economic and security future, so they decided to emigrate to Canada, but Canada’s rules at the time required perfect health and Borys had poor hearing due to scarlet fever as a child, so his family was rejected and remained on the farm in Chesnyky.

In the summer of 1939, Borys passed his last exam and graduated from the gymnasium, with no job prospects, but his hands were welcome on the family farm. Although they were aware of the Anschluss and Hitler’s threats against Poland, Arsen writes that few Jews in the Rohatyn area were well-informed about the ideology and practice of National Socialism, and that even the Lviv-based Zionist daily newspaper Chwila “showed considerable ‘modesty’ in these matters”. It seemed to the Akselrads that these concerns were far away, and they did not want to believe the worst. When September 1 and the outbreak of war came, many in the villages, whether socialist or Jewish, hoped for the arrival of Soviet troops instead of German; when in fact the Red Army came, for a short while the landless peasants benefited from distribution of arable land and livestock, but things soon changed for everyone.

Under Soviet Occupation

Less than a month after the arrival of Soviet administrators in the Rohatyn district, they introduced free seven- and ten-grade education systems for village and city students, respectively. Due to a shortage of teachers, they also opened a teacher’s training institute in Stanislaviv (today Ivano-Frankivsk), to which Borys applied and was accepted to be trained for teaching history, with a monthly stipend. Borys left his family home together with friends and fellow teaching candidates Bohdan Hryvnak of Chesnyky and Ivan Kyk of Pukiv. Intensive daily lectures and self-study followed at the school in Stanislaviv, which had been a monastery until it was closed by the Soviets. One day after a few teaching candidates had disappeared from the classes, two visiting “comrades in civilian clothes” began interviewing Borys and the others about the political views of the missing students and others, and then interviewed them again when another of the students silently disappeared; later Borys heard that the missing students had moved through the Carpathian mountains to Kraków, capital of the Nazi General Government and home to the anti-Soviet collaborationist Ukrainian nationalist organization of Volodymyr Kubiyovych.

In July 1940 Arsen passed his final exams and was assigned to work at a new school in the village of Viktoriv north of Stanislaviv, teaching history and geography, so he became economically self-sufficient even as his family’s fortunes were falling under the Soviets. Arsen was then reassigned to a school in the village of Sapohiv just across the river; during this time he shared half of his salary with his parents while they tried to hang on in Chesnyky.

In late June the German invasion of Soviet-occupied eastern Poland began with bombings of the Stanislaviv airfield and other military targets. Soviet troops retreated east on trains while local collaborators donned German uniforms and ordinary people set off on foot if they had homes elsewhere; Arsen joined the throngs and returned to Chesnyky. After several days at home while many others were traveling east, Arsen was taken captive one night along with other male villagers who had been active in local socialist politics, or had worked in Soviet teaching and other roles, or were Jews; Borys’s brother and father were brought to the same place the next evening. The men were held for a few days, then interrogated and beaten; Borys took a heavy beating for his membership in a Komsomol during his teaching service. He was hidden after the beating and recovered sufficiently from his wounds to walk home two weeks later; he heard from other victims that the beatings were worse and sometimes fatal in places with higher percentages of Jews, such as Stratyn, Kniahynychi, Bukachivtsi, Bilshivtsi, and elsewhere. Arsen notes that these “bloody Bacchanalia” were conducted by local underground OUN units, before the arrival of the Nazis; the leader in Chesnyky later became an officer in the local Ukrainian auxiliary police.

Under German Occupation

Not long after Arsen’s return to his family, and while they were gathering the harvest for distribution to neighbors, the anticipated trouble came: an order from the same people who had beaten Borys, for the family to leave Chesnyky for Rohatyn within three days, so there would remain no Jews in the village. Borys’s mother made arrangements to live with the Reichbach family in Rohatyn, and the entire Akselrad family walked with a loaded cart and plus two cows and two horses to Rohatyn via Pukiv, where they struggled to keep their animals from locals who tried to take them away. The German military arrived soon after, and were met in Rohatyn by crowds with flowers and banners in German and Ukrainian.

Aggression against Jews began on the third day of occupation. As also reported by other survivors of the Rohatyn ghetto, Jews were confined in a limited area, forced to wear an armband with a Star of David, their residences outside the ghetto were confiscated, they were forced to work unpaid in hard labor on roads and military agricultural projects, and they were rounded up, threatened, and beaten. Arsen was put to work as a blacksmith’s assistant in the Babintsi neighborhood of Rohatyn, where his large stature, “Aryan” features, and fluency in Ukrainian allowed him to blend in while outside the ghetto each day. Hunger became a serious problem in the ghetto, and the mistreatment of Jews, especially elderly males, increased.

One day during this period Arsen’s Ukrainian friend and fellow teacher from Chesnyky, Bohdan Hryvnak, went to the blacksmith shop and in a private conversation offered Borys his Greek-Catholic birth certificate to help Borys pass as a gentile; Bohdan said he would get a replacement for himself through his church connections. Arsen agreed; this agreement would save Borys’s life, and cost Bohdan his. Bohdan also gave Borys his prayer book to study, to better take on the role of a devout Ukrainian.

The stresses on the Jewish population in the ghetto worsened, with increasing German demands for hard currency and other valuables, causing strife between Rohatyn Jews and those moved to the ghetto from surrounding villages. Arsen used his false ID and wearing a cross and Ukrainian clothes to take the Reichbach’s daughter Dzunia under cover to her mother’s family in the village of Hrusiatychi near Fraha, but they returned to Rohatyn when they learned that the Jews in Hrusiatychi were soon to be moved to the ghetto in Novi Strilyshcha. Meanwhile, in Rohatyn, only those Jews sent out to work as slaves could get food and shoes; preschool children and the elderly died from cold and starvation in the streets, their bodies stacked and taken on carts by the Jewish police to be buried in mass graves in the “new” Jewish cemetery.

Arsen’s friends Mariika and Ivan Kyk, with who he sheltered in the village of Melna. Image from the memoir.

In January 1942, the Ternopil Gestapo ordered earthworks to be performed by 500 men digging every day; Arsen’s father and brother were assigned to this task, rumored to be for a tile factory on the road from Rohatyn to Putiatyntsi. Not enough able men were available, and in winter weather on an unprotected hill the progress was slow; the men were told their goal was to dig a pit 10x8x4 meters by April. On the morning of 20 March, Borys went to work at the blacksmith shop early as usual, his father and brother were sent early to work at the pit, and the first aktion descended on the Rohatyn Jewish community. Arsen’s father and brother were shot with the rest of the work detail; the rest of his family was taken from their home in the ghetto, and all were killed at the pit. Of the Akselrads and Reichbachs, 23 people in total in one house, only Borys and Dzunia survived, he with the blacksmith’s family and she by hiding in the attic of the house in the ghetto. Arsen believes that other survivors including Rosette Faust Halpern underestimate the number of Jews killed, and that 4,500 from the Rohatyn district died on the hill that day.

At Dzunia’s request, Borys stayed in the Rohatyn ghetto for a while after the aktion. He used his false identity to walk outside the city to see the site of the mass killing and burial, with its deep impression in the soil. Soon it became too dangerous to stay, as Arsen was able-bodied and the Judenrat needed men it could assign to the German work details. So one night he left the ghetto to meet with the Hryvnak family in Chesnyky and confirm his plan to pass as their son Bohdan; he then returned to the ghetto for his last time. Unable to do anything for Dzunia, in April Borys left for the village of Melna not far from Novi Strylishcha, to shelter as Bohdan with the family of his friend and fellow teacher from Pukiv, Ivan Kyk. Borys stayed with them until the middle of May, but learned that his presence in the village was making life dangerous for Ivan and his family. So Borys left by night, and went by train to Ternopil, hoping to find farming employment with his fictional identity.

Living and Working with a False Identity

By luck Arsen encountered an attorney in Ternopil who was curious about his assumed background and his motives but generously helped him find an internship on a folwark in the village of Shliakhtyntsi, about eight kilometers northeast of Ternopil center. The manager of the folwark, a man named Tsyshevych (Czyżewicz) from western Poland, seemed to understand Arsen’s situation but did not discuss it openly. He housed Arsen at the apartment of another worker named Serediuk, where Borys mimicked as best he could the customs and prayers of a devout Greek Catholic, and joined Serediuk in conversation about current affairs; Serediuk still hoped that Ukraine could become an independent state after the Third Reich achieved their military goals.

Arsen’s initial work included oversight of a dairy farm and a garden crew, with both management and training to prepare him for a degree program at the agrarian university in Dubliany, north of Lviv. As part of his dairy work, he sometimes went with milk wagons to Ternopil, and during this time he twice saw columns of Jews being led to trains and on to their murder at Bełżec. When the Jewish New Year came, he thought to visit the Rohatyn ghetto under the guise of visiting his Hryvnak “family” in Chesnyky, and he was granted several days off. Nervous about being recognized on the train at stations near where he had lived, he nonetheless arrived in Rohatyn safely and met Dzunia at her second-floor room in the ghetto. They spent a day together, and Arsen surveyed the situation: famine, illness, and a desperate hope that prepared bunkers would shield those who had survived the March aktion from further danger. But the next morning, on Yom Kippur, loud banging announced another aktion; Dzunia disappeared into a hidden bunker which Arsen considered too small for him, so he hid under his unmade bed and somehow escaped notice; the Germans went upstairs in the house but did not search under the bed. Although he did not witness specific acts of betrayal in these events, Arsen blames the “Jüdischer Ordnungsdienst”, the Jewish ghetto police, for secondary searches which exposed Jews in hiding and enabled the theft of their belongings.

Arsen composed himself, assembled his disguise, and left the ghetto quickly; he was almost immediately stopped by an officer of the Ukrainian auxiliary police. Arsen declared himself to be Bohdan Hryvnak, and asked to see Stepan Sheremeta, the deputy chief of the police, a man who had fought alongside Arsen’s father in Italy during World War I. When the two men were alone in Sheremeta’s office, the policeman told Arsen to hide in the hay in a police stable; two days later, after the aktion was over, Sheremeta silently released Arsen from the stable, and he returned to Ternopil by train. Arsen would not return to Rohatyn until after the war.

Gradually Arsen/Hryvnak became an accepted part of the folwark crew and the village of Shliakhtyntsi; he made more trips into Ternopil on business, but worried that he would be recognized. Christmas came and then the spring of 1943. News reports were sketchy, but the German defeat at Stalingrad unsettled those in the area who preferred the Nazis to the Soviets. On Easter, Bohdan Hryvnak’s father Symon came to Shliakhtyntsi pretending to visit his son, giving Arsen invaluable cover and helping him to better understand the Easter liturgy in Galician Greek Catholicism; Borys passed his “test”. The summer began, without Arsen learning of the Rohatyn ghetto liquidation in early June. At the end of summer, again the farm had to give half of everything harvested to the German military.

Arrest and Detention at the Ternopil Prison

In September 1943, Arsen was one of ten men detained at the farm in Shliakhtyntsi by the German Sicherheitsdienst (SD, a branch of the SS) without explanation. When they were taken to the Gestapo prison in Ternopil, based on the many other prisoners held there and on the interrogations which followed, Arsen concluded that he was thought to be a communist sympathizer or a Ukrainian insurgent – either way, a partisan opposed to Nazi rule. After several days a group of about 500 prisoners was transported at night by covered trucks to what they guessed would be their death by shooting in the forest, but instead they were loaded into ten locked freight cars and sent by rail to Lviv and the notorious prison on Łącki (Lonski) Street. Here the prisoners were sorted, and Arsen was grouped with younger people under age 35, loaded onto another closed wagon and taken with many others to an unknown open field where they remained, mostly locked in the wagons, for several days. Arsen remained disguised as Bohdan Hryvnak, alone as a Jew among a few Poles and many Ukrainians.

Transfer to Birkenau

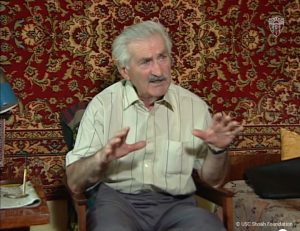

The tattoo number 155103 applied to Arsen’s arm at Birkenau,

seen in 1997. Image © USC Shoah Foundation.

The Poles among the prisoners correctly anticipated the train’s final destination: in early October 1943, they arrived hungry and thirsty at the Auschwitz II-Birkenau Nazi prisoner-of-war camp near Brzezinka, Poland, 400km from Lviv; five of the prisoners did not survive the journey. Arsen and the others were systematically registered, tatooed, disinfected, shaved (the hair on their heads cut in a pattern which would immediately identify them, should they escape), assigned to blocks (barracks), clothed, and issued their “badges of shame”; Arsen’s was a red triangle (for political prisoners) with an “R” (for Russians and other Soviet citizens). The Ukrainians Arsen knew from his region were assigned the letter “P” for Poland. New arrivals were quarantined with monotonous in-camp labor for two weeks; meager meals and strict controls on movement and behavior began immediately. Arsen learned quickly that to survive he needed to bond with other men from his region for mutual help. But in mid-October, before he was assigned to regular labor details inside or outside the camp, Arsen was transported with many other prisoners by rail to the Buchenwald concentration camp near Weimar, German, some 700km away; he arrived with many other living and dead prisoners on 23 October 1943.

Forced Labor at Buchenwald and Düsseldorf

Scenes and situations from Birkenau were now repeated at Buchenwald: electrified barbed wire surrounds, crematoria, disinfection, clothes and triangle badges, meager rations, guard towers, barracks, abuse. As at Birkenau, with poor and slight food, wasting illnesses such as diarrhea were frequently and quickly fatal. One difference, which reflected the camp’s location and the progress of the war: here the guards were younger, as if new recruits.

Two of the men who befriended and protected Arsen at Buchenwald:

Vasyl Stetsiuk and Roman Lehin. Images from the memoir.

Again the new prisoners quickly surveyed the others for “their own”; in Arsen’s case, as Bohdan Hryvnak, he sought and found Galician Ukrainian prisoners from the Ternopil area who were capable and humane. The prisoners also had a scheme for dealing with thieves and informers in their midst: the suspects were “allowed to leave”, typically by knocking them into the latrines and down the chute which fed the sewer; even these dead had to be recovered and burned.

Arsen was assigned to work at a stone quarry, hard work which was considered a death sentence. Normally he joined more than a hundred other prisoners per day walking to and from the work about two kilometers from the camp. Stone was blasted by detonators, after which individual or pairs of prisoners had to carry the blocks to the top of the quarry. This work, nearly beyond Arsen’s strength, continued six and a half days per week for two months. Then he was assigned with about 500 other prisoners to a construction site near Düsseldorf, roughly 400km to the west, where he did more heavy lifting, but now of steel rails and crushed rock for a rail line. Still later he was assigned to craft work, assisting a welder, assembling what he learned after the war were parts for V-1 cruise missiles to be launched against London and the English coast. However, the Allies were aware of the arms factory work and bombed several of the workshops at the facility where Arsen was assigned; apparently afraid the prisoners would escape in one of the bombing raids, in April 1944 they were transferred back to Buchenwald. Arsen was then assigned to a workshop in a nearby Gustloff Werke where he operated metalworking lathes and mills, much easier labor than he had had before.

Prisoners working at forced labor in a Gustloff Werke factory in Buchenwald.

Source: USHMM.

British and American bombers began to strike German factories producing war materiel in the summer of 1944, and in late August incendiary and explosive bombs fell on the workshops ringing the Buchenwald camp, but did not strike the camp itself; prisoners working in the factories were killed, but those like Arsen who were off work at the time were spared. A week later Arsen was transferred with others to factories outside the city of Halle, north of Weimar near Leipzig, where aircraft workshops were built underground in the salt mines to protect them from Allied bombs. Now he was assigned to concrete work, in 12-hour work days with no days off. At the beginning of February 1945, the prisoners were again returned to Buchenwald for miscellaneous labor, where by chance Arsen met another Jew from Rohatyn, Heinrich Schnap, also in disguise as a Ukrainian (who also survived the war, and later settled in Frankfurt).

US Air Force documentation of bombing of the Buchenwald munitions factories

and storage in 1944. Source: USHMM.

Three weeks later Arsen was again transferred, this time to the Buchenwald sub-camp of Bad Salzungen, a deep (500m) former salt mine where he and hundreds of others worked in shifts on the assembly of secret German weapons. During this time he met and befriended an Armenian prisoner, with whom he developed a close protective bond. Then on 6 April 1945, all of the prisoners in his detail were assembled above ground and marched in rows of four to an unknown destination. When the convoy was spotted by Allied planes, the guards turned the prisoners toward the forest for cover, but there were too few guards to herd everyone, and as night fell Arsen and the Armenian took a chance to escape and leapt into a ravine; the guards shot at them with automatic weapons but did not follow them, so as not to lose the rest of the prisoners. Arsen was uninjured, but his friend was seriously wounded; later that night he died in Arsen’s arms. Borys Akselrad, masquerading as Bohdan Hryvnak, vowed then that if he should survive he would take the surname of his Armenian friend: Arsen.

Arsen made his way to a clearing and some agricultural buildings, where he tried to sleep in a haystack. Starving, the next day he approached two French prisoners working as farm slaves, and they fed him for the next two days in hiding. When a tank unit of Patton’s American army arrived at the farm, Arsen came out of hiding. He was weighed (48kg), then clothed and put on a medically-supervised diet; the US troops already had experience with former prisoners of concentration camps, some of whom suffered terribly from the change of diet after they were freed. Arsen and other former prisoners contemplated whether, if they had a choice, they should return to their homelands, now under Soviet rule again. After meeting in Weimar with agents of various countries and organizations, including the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC), ultimately Arsen decided with some new friends to return to Soviet Ukraine, where he could at least hope to find old friends and perhaps some family.

Under the Soviets Again, and Return to Rohatyn

In June 1945, Arsen and others were taken by car and accompanied east by two Red Army soldiers to the prewar Polish border. He and ten of his companions then traveled by overloaded train (they rode on the roof of a freight car) to the Warsaw suburb of Praga, across the Vistula River from the destroyed downtown; they remained for a week, observing how the residents were re-making their lives in the ruins. Then they traveled farther east by train to Brest, incorporated into Soviet Belarus during the war, now a major Soviet checkpoint for former camp prisoners and forced laborers aiming to return to eastern lands. Arsen did not feel welcomed by the Soviet authorities, who questioned what he may have done to survive.

Arsen was placed on a train with many others, and sent into the unknown east, with three days’ dry rations and no instructions. In the end he arrived at the town of Yenakiieve near Makiivka in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine, and was put to work in prison-like conditions in the coal mines above and below ground. Despite surviving a year and a half of camp conditions including poor food and sanitation without falling ill, at the coal mines Arsen became quite sick, was hospitalized, and was diagnosed with pleurisy compounded by effusion in his lungs. He was treated for several months and improved, though the condition would recur for the rest of his life. In January 1946 he was granted six months’ leave to return to Rohatyn, and arrived just after Eastern Christmas.

The Rohatyn city leaders welcomed Arsen and helped him find both lodging and work, which he began with the city council. Borys sensed significant ethnic tension in Rohatyn as a result of the shifting power centers during the war, and heard about ongoing armed struggles between the Soviet security forces and the old and new Ukrainian national organizations. The situation was even worse in the villages, as Arsen discovered on an escorted visit to his native Chesnyky. He learned that his younger brother Natan had survived the aktion of 20 March 1942 by jumping into the pit alive and covering himself with corpses, then crawling out at the end of the killing and passing by night to a village 12km away, where he was temporarily sheltered on a farm. Natan made himself a hiding place outside a nearby village, but a year later was discovered and murdered by members of the security service of the OUN (SB, or “Esbists”), according to two elderly Ukrainians Arsen knew well from before the war in Chesnyky. Overall Arsen learned the names of 54 people from Chesnyky and the area who were killed, nearly all the “wrong” kind of Ukrainians according to their executioners; he also learned about Poles killed in Pidkamin and other villages in the district.

A few months after his arrival, Arsen was offered the post of director of the electrical works in Rohatyn, which was left in disarray after the German occupiers stole the diesel power generator when they retreated in 1944. Arsen was astonished at the offer, since he had no prior electrical experience, but among the team of ten were several veteran electrical workers who had worked with Mocie Stryer, the Jewish former power plant manager who had emigrated west in early 1946. Arsen accepted the job offer, and with his team was able to raise funds through a subscription campaign for future service, purchase a 150kW generator in Lviv, install and connect it to the existing network, and add new lines for subscribers and others – all under the eyes of local representatives of the Soviet NKVD, and largely without formal documentation. After everything was working well, in February 1947 Arsen was suddenly replaced as plant director by a Communist Party member, and he left Rohatyn for temporary work in the region.

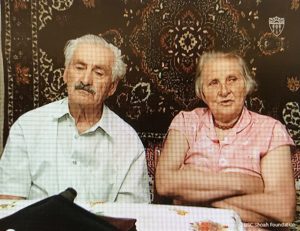

Marriage and Moving to Ivano-Frankivsk

Arsen held a variety of jobs in the economy and labor organizations of the grain and meat/dairy industries of Prykarpattia, traveling often to learn and to develop mills and other processing plants of the Soviet planned economy system; he also studied and graduated from two technical and financial institutes based in Kyiv, to further his career. He married a woman, Olena, from Poltava, and with her raised two sons; after living mostly in temporary housing in Lviv and the region, in 1971 he moved with his family to Ivano-Frankivsk. Here he became the manager of a collective furniture factory with 2,000 employees, and worked a 6-day, 12-hour schedule like his team.

In 1987 Arsen was joined by the then head of the Rohatyn city council, Roman Stehniy, to select a location to place a memorial at the site of the killings which followed the ghetto liquidation. Machinery which was preparing land at the first proposed location unexpectedly opened a mass grave of human remains, so the grave was closed again and the memorial was instead sited nearby.

After 18 years at the furniture collective, and at the age of 68, Arsen surprised those who knew him by joining the Communist Party, and he retired after his last years of work, as a machine operator in a cooperative. In 1989 he at last received his concentration camp records as Bohdan Hryvnak via the Arolsen Archives (formerly the International Tracing Service), and with that documentation in 1991 he was able to record his camp experience as Borys Arsen in the city court of Ivano-Frankivsk.

As a Representative for Regional Jews

From 1991 Arsen participated in local elections and socialist organizations of the newly-independent and democratic Ukraine, but was disillusioned at everyday infighting and left politics some years later. In 1994 he was elected head of the local Jewish community, leading an association of Jewish former prisoners of ghettos and Nazi concentration camps, a total of 34 survivors in and around Ivano-Frankivsk. In 1996 his group began to receive “mutual understanding and reconciliation” payments from Germany and Switzerland as well as the treasury of the Ukrainian National Rada (UNR). As a regional leader, he also met with representatives from the Steven Spielberg Foundation and Yad Vashem; Arsen made trips to Israel in 1997, 1998, and 2000. In 1997 he received from Yad Vashem on behalf of Bohdan Hryvnak a Certificate of Honor and a posthumous award of the medal for Righteous Among the Nations, presenting those to Hryvnak’s sister Mykhailyna in a ceremony in Chesnyky. In June 1998, Arsen met with Rohatyn Jewish survivors from Israel and the US, and joined them in commemoration of the destroyed Jewish communities of the Rohatyn district, and the dedication of a series of memorials funded by the group with the support the Rohatyn city leadership. In 2002 to 2004, Arsen recovered from a debilitating recurrence of his lung illness, finally completing and publishing his memoir at a printer in Nadvirna.

Elements of the Memoir with Value to Rohatyn Studies

Arsen testifying with Mykhailo Vorobets at Rohatyn’s south mass grave site in 1998. Image © USC Shoah Foundation.

As for all of the Jewish personal memoirs of wartime Rohatyn, Arsen’s story includes vivid descriptions of the people and circumstances of his experiences, such as his difficult time in the Rohatyn ghetto, his evasion and employment with a false identity, his capture and incarceration as a “Russian”, and his eventual escape and freedom in Soviet Ukraine. Parts of his story are unusual for Rohatyn-area Jews and are thus valuable for the broader picture, including his prewar life on family farms in villages, his participation with Ukrainian friends and neighbors in prewar political activity, the mixed benefit for himself and his family of the initial Soviet occupation, his desperate survival in German prisons, transports, and concentration camps, and his postwar career in administrative and industrial functions under Soviet and independent Ukrainian governments. Throughout his memoir, Arsen is clear and specific with the names of people, places, and organizations, both good and bad. His voice is strong, and at times understandably angry.

Arsen pointing to features of Rohatyn’s town square as he testified in 1998. Image © USC Shoah Foundation.

In his effort to tell the larger story of the Holocaust in Carpathian Ukraine, Arsen includes the prewar histories of Rohatyn and a number of other significant regional cities and villages (Ivano-Frankivsk, Nadvirna, Kolomyia, plus his own Pidkamin and Chesnyky); he details the wartime destruction of the Jewish communities of these places as well. In many of the chapters, he quantifies the changing populations over time of the several religious and ethnic groups, not only in the major cities of the region but also in each of the key settlements in the Rohatyn district. Through his own historical research in newly-independent Ukraine, he also documents the demographic and economic impacts of the Nazi-led Holocaust: in the camps, on the transports, and through the requisition and theft of property, money, and other valuables. Thus his memoir presents his personal story within a kind of handbook on the Holocaust centered on today’s western Ukraine.

Embittered by the apparent willingness of some people to destroy others’ lives for their personal political and/or economic gain, at several points in the book Arsen pauses to consider and present evidence of the manipulation of events, acts, laws, and speeches to first exploit the “new order” when power changed hands and then later to cover up former allegiances when power changed hands again. Arsen quotes from recorded proclamations and includes historical newspaper clippings and pamphlets to force remembrance of who said and did what during times which those people helped to darken. His memoir includes examples of false and dangerous speech from before the German occupation, then during the Holocaust period, the later Soviet period, and even from post-Soviet independent Ukraine. His Afterword surveys residual covert and overt antisemitism in the Prykarpattia region, as a warning to neighbors, other citizens, and political figures.

The Rohatyn Jewish survivor Dzunia Reiss (known as Maria Tsapar after the war) during an interview with RJH in 2012, together with Mykhailo Vorobets. Photo © 2012 RJH.

Arsen recognized his gifts as a historian, a writer, and a witness, and his role as a Jewish community organizer and leader in the postwar period. He was clearly motivated to speak for the great many Jews who were forever silenced and for the few regional survivors, most of whom did not leave public testimony. Noting that the majority of survivors from regional Jewish ghettos emigrated abroad after the war, and that many of those found each other in foreign self-help and social organizations, he used the final chapter of his book to briefly document and give voice to those who stayed behind in the greater Ivano-Frankivsk area (including the Jewish survivor in Rohatyn known as Maria Tsapar, born Dzunia Reiss) through their circumstances and their stories. More than a dozen survivors are documented, most with photos from their later lives, and Arsen is careful to tabulate the names and addresses of the righteous gentiles who aided these people and himself.

Arsen used as sources for the broader history of the Holocaust a variety of historical newspapers, the works of other local and academic historians, evidence from the Nuremburg trials including the Katzmann Report, the published and unpublished memoirs of other Jewish survivors and witnesses from today’s western Ukraine, as well as Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, and the holdings of several other archives, especially in Ivano-Frankivsk. In the two decades since Arsen wrote his memoir, global historical research on the Holocaust has brought many more facts and resources into public view, all of it now accessible (with translation) in independent Ukraine; Arsen’s own historical research, strong as it was at the time, is no longer a primary source. But the people- and place-specific information he provides about the Holocaust as a witness in and around Rohatyn is much more detailed than what is available in any other resource we know of, and could provide a starting point for further research by Ukrainian gymnasium or university students from the area, for other local historians and journalists, and for Jewish family historians and others.

Additional References

Nearly all of the information presented here is summarized directly from Arsen’s published memoir. A small number of additional biographical and historical details are from other survivors’ memoirs and published academic histories.

Arsen also gave a video-recorded interview with the USC Shoah Foundation in 1996; the VHA interview code is 31757. A related interview was also given by Bohdan Hryvnak’s sister Mykhailyna Hryvnak; the VHA interview code for her testimony is 44311.

This page is part of a series on memoirs of Jewish life in Rohatyn, a component of our history of the Jewish community of Rohatyn.