![]() Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Rosette Faust Halpern; A Journey Through Grief – The Autobiography of a Holocaust Survivor; lulu.com; 2013.

Introduction

[T]here would be no words that could adequately describe the indebtedness I owe to the courageous women who were instrumental in my surviving the Holocaust…

Thus begins a memoir written by Rosette Faust Halpern (born Roza Faust, and known as Rozia and Rozka to childhood friends and family), a survivor of the Holocaust in Rohatyn. Rosette was 21 years old when the German military occupied Rohatyn; from that time, while she always needed her own wits and daring to avoid detection and escape death, she was given essential shelter, false identity, food, and information by a large number of non-Jewish friends and strangers over the next three years. Without luck and constant aid, Rosette would have joined the vast majority of Rohatyn’s Jews, who perished in or near the town.

In addition to its harrowing tale of survival, the memoir also provides portraits of family and friends before, during, and after the war, and a survey of Rosette’s life on two continents across almost a century.

The book was released through the on-demand publisher lulu.com and is still available new as hardback or paperback from that source. It is also available in libraries, and good-quality new old stock and used copies are also readily available from independent booksellers.

This page includes an outline of the book’s organization, a brief synopsis of Rosette’s life as described in the memoir, a summary of memoir elements useful to Rohatyn studies and other themes, and a few references to additional materials relating to Rosette’s story.

Organization of the Memoir

Divided into twenty-five chapters, the book begins with an introduction to the town of Rohatyn and its Jewish community. Then eight chapters describe Rosette’s immediate family: her parents and the siblings who preceded her. The memoir then quickly covers Rosette’s birth, her school years with friends and family, and her first love, on the eve of the war.

Time then slows in the story, as the war erupts and engulfs Rohatyn. The middle part of the memoir covers the five grueling years from Soviet occupation through German occupation and ghetto life to hiding and eventual liberation, while Rosette relates what she saw and heard, who she lost, and who she found.

The remainder of the memoir covers her postwar journeys and her efforts to build a new life in Europe and then America. Throughout the book, and especially in this last section, the memoir is augmented with a very large number of photographs of family and friends before, during, and after the war, plus photocopies of documents, maps, and even sheet music relevant to her story, all carefully annotated with names and dates.

A Brief Summary of the Author’s Life

Faust Family Klezmorim. Rosette’s father David Faust stands at right, and her grandfather Moshe Faust sits at left. Source: The Faust-Rothen Photo Collection; image provided by Alex Feller.

Rosette was born in Rohatyn in 1919, into the well-known Faust family which had lived in Rohatyn and worked as musicians for four generations before her. Her father David Faust was one of several professional traditional klezmer musician brothers who played under the leadership of their father – Rosette’s grandfather Moshe – together with the husband of Moshe’s sister and others. David became first violin and leader of the small but popular orchestra when Moshe retired.

The Faust family in 1924. Rosette stands between her parents. Source: Faust-Rothen Family Collection;

image provided by Alex Feller.

David had served in World War I, far away from home and out of communication with the family for three years. Rosette’s birth to David’s wife Deborah (Dvora) followed five other children by eight years; her sister Berta (Beila) was twelve years her senior. Rosette’s parents were in their forties when she was born, making her childhood unusual but creating a strong loving bond, especially between mother and daughter. Life at home concentrated as Rosette’s siblings one by one married and left home (two went to America) during her childhood.

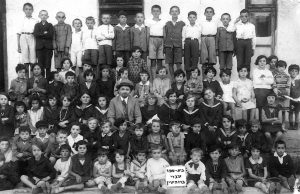

A Rohatyn Hebrew school class in the 1930s; Rosette sits second to the right of her teacher, Mr. Edelstein. Rosette said she was one of only four children in the photo to survive the Holocaust. Source: Rohatyn Yizkor Book.

Rosette attended a Polish elementary school in Rohatyn, but took classes at the Hebrew school as well. Unsuccessful in her first attempt to attend a gymnasium in Rohatyn, she was instead accepted as an apprentice in a local clothing fashion atelier. She also joined a local chapter of the Zionist youth organization HaNoar HaTzioni, which promoted Jewish culture and history as part of social activities and language study.

Through activities of the youth organization, in 1934 Rosette met the law student Willy Halpern from Drohobych, six years her senior. Willy helped her with her studies and other activities, and Rosette became infatuated. After some time dating other people, the couple affirmed their feelings for each other and began making plans. Then in 1939, the war came.

Rosette with friends in 1939. Left to right: Rozka Faust, Hannah Weiderker, Lorka Mark, Peppa Bohnen, Malka Kanfer, Babtcha Wachter.

Source: Bohnen Family Collection.

Life in Rohatyn was much disturbed by the Soviet occupation, but the Faust family adapted. Rosette was accepted into a Russian-administered Ukrainian gymnasium, which would give her language skills useful in the coming dark years. She and Willy made wedding and household plans while working at various jobs. But in mid-1941, Germany invaded the Soviet-held parts of Poland; Willy and his brother Izio were recruited into the retreating Soviet army, then assigned to hard labor at a coal mine in Soviet Kyrgyzstan in central Asia, almost 4000km away. Rosette would have no news of Willy for the duration of the war.

The arrival of the German army to Rohatyn brought trouble and terror to the town’s entire Jewish community. Rosette’s father was beaten during anti-Jewish violence in first week of German occupation. Rosette and her parents were moved with all the town’s Jews into cramped quarters in the newly-established ghetto. The ghetto became a prison, and increasing violence culminated in the aktion of 20 March 1942, when most of Rohatyn’s Jews were forced from the ghetto and killed at pits south of town. Rosette and her family escaped by hiding in cellars and bunkers under houses in the ghetto, but many of her school friends and cousins were lost.

In the aftermath of the aktion, the wife of an important local Ukrainian official, Anna Kosmyna Baczynska, who had as a child been a music student of Rosette’s father, came to ask David to teach music to her boys; David agreed and soon arrangements were also made for Rosette to regularly visit the Baczynska family as a dressmaker and as a German-language tutor to the family’s children. Rosette now had a permanent pass out of the ghetto, and food for herself and her family. Still, she slept at home in the ghetto and endured another aktion in September, hiding in a family bunker. Later she was caught smuggling meat into the ghetto, was arrested and then whipped during interrogation.

Mrs. Baczynska and Rosette’s high school teacher Mrs. Savitzka began to look for alternate, more secure shelter for her in their homes, in violation of German orders and at mortal risk to themselves and their families. An opportunity came for Rosette to take the identity of a girl about her age, Darka Wasilkiewitz, who had recently died of pneumonia after her parents had been deported by the Soviets. Under this name but with her true identity known to Oksana Bilej, a Ukrainian friend of Mrs. Baczynska, Rosette went to the village of Skomorokhy about 25km to the south, to help care for Oksana’s mother, where she remained, posing as Ukrainian for about three months. While she was away, in early December Rohatyn’s ghetto was attacked in another aktion; fortunately Rosette’s family was spared, but when she heard news of the attack she resolved to return to her family. Rosette was aided in her return to Rohatyn by Oksana and Mrs. Baczynska.

Although her parents urged her to accept refuge away from Rohatyn, Rosette stayed with them and with Willy’s parents in the ghetto. But by late spring, at the urging of her parents and Mrs. Baczynska, she was spending nights in hiding at the Baczynska home outside the ghetto. Rosette was there on the morning of 6 June 1943, when she was awakened by shooting during the liquidation of the ghetto. Her own parents were beaten to death, along with her youngest brother, and another brother was shot with his wife and three children; all were buried in a mass grave north of town. In all Rosette lost nearly 50 members of her extended family in Rohatyn.

Rosette’s brother Leon Faust and his wife Cyla; they were shot with their children during the ghetto liquidation. Source: Chaya Rosen.

Rosette remained in hiding in the Baczynska home for nearly a year, until the advancing Soviet army threatened the resident Germans and they prepared to destroy utilities in Rohatyn, requisitioning the Baczynska house for their command; the Baczynskas and others had to evacuate the town, and Rosette had to find other shelter. With food and water packed for her by Mrs. Baczynska, Rosette left the house and headed toward the ruined ghetto, but was spotted and forced to hide in a barn, where she remained for days by rationing her food and water. Thirst eventually drove her to the basement of Mrs. Savitzka’s building, which had running water. Mrs. Savitzka found her there, gave her food and access to other rooms. Over the next days, to avoid detection she moved from house to house, basement to attic, desperate to escape detection in the last moments of occupation; she was helped by several Ukrainians who had known her before the war, and one whose husband worked as a driver for the Germans.

Then the Germans left in haste and without blowing up the town; the Soviet army arrived shortly after, announcing liberation to those still in hiding in Rohatyn. Rosette was placed with a family of Jehovah’s Witnesses who cared for her, and in the following days the family helped her and the few other Jews who had survived to find each other in town. She walked to Bukachivtsi, where her sister Berta had lived with her family before the war, and was tearfully reunited with them; Berta described how they had survived in a bunker in the Rohatyn ghetto with their parents, and then Berta and her family escaped into the forests.

Rosette stayed with her sister’s family in Bukachivtsi for a short while, then returned to Rohatyn in the hope of getting word about Willy; she took a job in the post office in order to monitor letters and other communication into town. One day she was notified by a Soviet official that Willy was alive and in Kyrgyzstan, and his letters began to arrive. Rosette resolved to go to him.

Arrangements for the journey during wartime and under Soviet administration were difficult, but after traveling by train across eastern Europe and western Asia for five weeks, she was reunited with Willy on the day before Nazi Germany’s surrender and the end of the war in Europe. They married in a civil ceremony the next day, then stayed in Kyrgyzstan for a year, organizing a school and helping at a local hospital. Rosette miscarried her first child and became quite ill, but recovered.

In June 1946, Rosette and Willy were repatriated to Poland under terms of the Yalta Conference, along with many other Polish Jews. Since the borders of Poland were redrawn at the end of the war, and Rohatyn was now part of Soviet Ukraine, they were settled in Silesia, in the former German town of Reichenbach, called Rychbach after the war and now renamed Dzierżoniów. There, they found several other Rohatyn-area Jewish survivors, including her sister Berta with her family.

They remained in Poland only about a year, for fear of anti-Jewish pogroms which they heard about in several Polish cities; while there, they organized and participated in new Zionist organizations. Rosette’s brother Jack in America arranged for the couple to reach Paris as a gathering point for Jews wanting to emigrate to Palestine; her sister Berta was able to emigrate with her family, but lacking funds and residency, Rosette and Willy remained in Paris.

The couple were treated with kindness by neighbors and strangers in Paris, and with the help of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC, “the Joint”) Willy found work and obtained legal residency in France. Rosette enrolled in a school of fashion design and worked part time in an atelier. In late 1950, their son David was born in Marseille, and the couple put Israel plans on hold when they had an opportunity to join Rosette’s brothers and other family in America; they arrived in America in late 1951. Unable to use his Polish law degree, Willy studied engineering at night, earned his degree and began a career as an engineer. Rosette earned a college degree from the Fashion Institute of Technology, enabling her to work in freelance technical design for America’s ready-to-wear clothing industry. David grew up, attended college, and became a dentist with a family of his own.

Rosette volunteered for several Zionist organizations in the US, becoming president of her local chapter of the Hadassah women’s group, and she participated in community support for the nearby Jewish-sponsored secular university, Brandeis. In 1996, she recorded video testimony for what is now the USC Shoah Foundation. She also participated with the Rohatyn Jewish survivors’ and descendants’ group from Israel and America in planning memorial markers for the mass graves in Rohatyn, and joined the several groups who gathered there in 1998 for commemoration. Overcome with emotion, Rosette was unable to speak at the memorial events, but was comforted by her many family members who traveled with her, and over the two days was able to visit the key sites of her life and her family’s deaths.

Willy became ill in late 1998 and died in spring 1999; a few years later, Rosette moved close to the home of her son David, who helped her in the last decades of her life. During this time, as Rosette assembled the notes and details that would become her memoir, she struggled with the dark memories which her diary, photos and documents brought back to the present. At times she had to set the work aside to stop the nightmares from returning. But she continued to meet, speak, and work with other survivors and descendants to keep the memory of the lost Jewish community of Rohatyn alive.

Roza/Rozia/Rozka/Rosette Faust Halpern passed away in 2017; she is survived by her son, his wife and two daughters, plus many others in the extended Faust family and in the Rohatyn Jewish descendant community who knew her.

Elements of the Memoir with Value to Rohatyn Studies

As in any personal memoir, Rosette’s early life experiences cover only a fraction of the breadth of history at her place and time, but Rosette’s memoir is filled with names and characterizations of a great many people in pre-war and wartime Rohatyn – not only of Jewish families but also Ukrainians and others she encountered in her struggle to persevere. With so few survivors of the Rohatyn ghetto, the people she names and events she describes can provide much-needed data to help link stories from other Jewish survivors and local witnesses to each other and to the events of the time.

One aspect of this is naming the victims, an important need in Holocaust studies. Rosette lists almost fifty members of her family who were killed, along with many other Jews she knew before and during the war (and at least one killed after the Soviet army returned to Rohatyn). Details about the people and specific events help provide much-needed texture to the glimpses of victims’ lives, and deaths. For many relatives, these glimpses may be the only info they have for some of their lost family. Some of the stories cross over to other testimonies, as of local Ukrainians who recently recorded their reminiscences for Yahad – In Unum.

Another aspect is naming the righteous gentiles who aided Jews at their own peril during the German occupation. Rosette was repeatedly given shelter, food, clothing, and more, and over extended periods of time by two families in particular. She gives full names and other details in her memoir, to aid further research to identify the families of people who helped her and others. In addition to Anna Kosmyna Baczynska from Cherche (who sheltered not only Rosette but also her friend Klara Wald Weisbraun) and her daughters Lydia and Marta, plus Oksana Bilej of Skomorokhy, Rosette names Michael Bilan, Katriusia Mosora, and her high school teacher Mrs. Savitzka of Rohatyn who provided her with support; another woman known to her only as Kasia helped not only Rosette but also the Horn family, despite the concern of her husband for their own family’s safety.

Rosette’s memoir also names perpetrators – German military leaders and local people who supported them – where she knew the identity of those who led the killings or betrayed Jews in hiding.

Besides the names, valuable information is available in the memoir to aid research on themes of pre-war Jewish society in east-Galician Poland, wartime eastward deportations under Soviet rule, ghetto bunkers, life in early post-war Poland, and the Jewish survivors’ and descendants’ organizations which formed in Israel and elsewhere from the 1950s.

Additional References

Most of the information presented here is summarized directly from Rosette’s published memoir. Additional biographical and historical details are from Rosette’s grand-nephew Dr. Alex Feller and niece Chaya Rosen, and from Rosette’s Yad Vashem testimony.

Rosette also gave a video-recorded interview with the USC Shoah Foundation in 1996; the VHA interview code is 21684. The interview includes several important details not present in her written memoir.

A brief excerpt of the early ghetto period of Rosette’s survival story also appears in the Rohatyn Yizkor Book as “A Diary of the Rohatyn Ghetto” [p.27 of the English section]. This text also appears in updated form in Leah Zahav’s “Remembering Rohatyn” [p.423].

An additional summary autobiography by Rosette is also included in Leah Zahav’s “Remembering Rohatyn” [p.536].

Rosette kept a handwritten diary during the wartime occupation years in Rohatyn, and she referred to that diary while writing her memoir “A Journey Through Grief”. To date, the diary itself remains unpublished.

This page is part of a series on memoirs of Jewish life in Rohatyn, a component of our history of the Jewish community of Rohatyn.