![]() Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

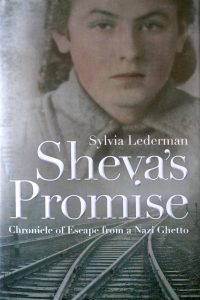

Sylvia Lederman; Sheva’s Promise – Chronicle of Escape from a Nazi Ghetto; Syracuse University Press; New York, 2013.

Introduction

Just one thing I ask of you: do not forget what happened to us and all our people… Don’t ever forget…

Those were the words of Sheva Weiler’s mother Gitel, as Sheva was preparing to leave the Rohatyn ghetto in November 1942; Sheva never returned to Rohatyn, but she never forgot her promise. Her book helps to preserve the memory of her family and the thousands of others who also died in Rohatyn during the war.

This page describes a memoir written by Sylvia Lederman (born Sheva Weiler, and known as Shevele to close friends), who was 24 years old when the German military occupied Rohatyn. The memoir spans only five years, from occupation to liberation and emigration, but during that time Sheva evaded capture and death in the Rohatyn ghetto, then escaped and survived by working under false identity in Lemberg (Lviv) and Germany before the war ended. Her story is a dramatic tale of cunning and luck, and especially of the kindness of others: she names several Jewish, Ukrainian, Polish, and German people who were essential to her survival in Poland and Germany and to her new life in America after the war.

The book is still in print and available from the publisher, as well as in libraries and on Project Muse; good-quality new old stock and used copies are also readily available from independent booksellers.

This page includes a brief summary of Lederman’s life during and after the war, plus several details from the memoir with particular value for researchers of Rohatyn’s history. As noted below, portions of the book also have significant relevance to researchers of other wartime places and issues, including aktions and the ghetto liquidation in Brody, the Janowska labor and transit camp in Lviv, forced labor workers in Austria and Germany, displaced persons camps in Germany after the war, and righteous gentiles who risked their lives to aid Jews during the war.

A Brief Summary of the Author’s Life

Sheva Weiler was born in Rohatyn in November 1916, during the devastation of Galicia caused by World War I; her father Laizor died serving in the war, three months after Sheva was born. She grew up living with her mother Gitel and her older sister Rose among other family and friends in Rohatyn. From the 1930s she worked to help support her family; under Soviet administration from 1939 to 1941, she worked in the only bookstore in town (“Knigokultur”). Through her work she was known to local Poles and Ukrainians, and she could speak Ukrainian fluently.

Within a month after German forces occupied Rohatyn, local Jews were expelled from jobs, the Jewish ghetto was established and Sheva’s family was forced into a single room in a house near a corner of the ghetto. The ghetto operated as a prison, Jews were required to wear an identifying armband; hunger became common. Like her mother and sister, Sheva had facial features which could appear “Aryan”, so despite the danger she frequently removed her armband and exited the ghetto in search of food, trading with Ukrainian townspeople she knew for supplemental bread and potatoes, sometimes for butter or cheese. She mentions in particular the Krupka and Babink families of Rohatyn who aided her and treated her fairly despite the prohibition to interact with Jews. Once she worked for three days picking potatoes in the fields of a friendly farmer outside the nearby village of Zaluzhzhia; the farmer’s family paid her with a hundred-kilogram sack of potatoes, and fed her during her work days, then continued to barter with her family for a while after.

Conditions in the ghetto worsened as more Jews were expelled from towns and villages in the district and were forced into cramped houses in Rohatyn. Crowding and lack of fuel in the winter caused older Jews to take ill and die, including Sheva’s grandmother. When the morning of 20 March 1942 brought Gestapo men into the ghetto for a major aktion, Sheva’s sister ran to hide in their outhouse, immersing herself in excrement to her chin; her mother was taken into a cellar hiding place by a neighbor. Sheva ran blindly out of the ghetto, through the adjacent village of Babintsi, and near to Kuttsi where she slipped and fell, passing out in the cold. A village woman there revived her and took her into her home, and with her husband kept Sheva in hiding as the houses were searched by Ukrainian police and Gestapo. From the village she could hear the shooting near the brick factory, at what is now the southern mass grave site. The next day she returned to the ghetto and was relieved to find her mother and sister alive, but she also learned of the deaths of many of her extended family and friends; only a fraction of the ghetto residents survived.

Following the aktion, many of the survivors and newly-arriving Jews from other towns in the region began to organize for self-help. Sheva helped to set up a hospital in the ghetto, but the patients and staff were repeatedly taken by the Germans for executions. Later she worked to establish a soup kitchen to feed ghetto residents who had no other access to food. She met several Jews from elsewhere in Poland who also had Aryan features, and together they planned means of false identity and escape with the help of a few ethnic Poles. And with other ghetto residents they dug a number of underground shelters beneath their houses.

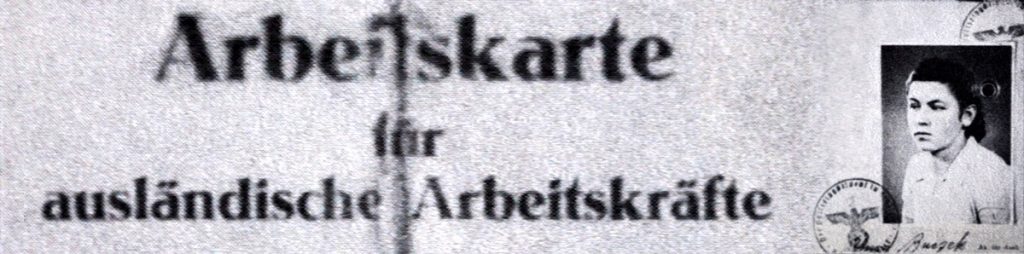

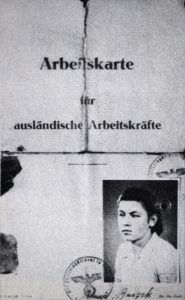

Sheva survived another aktion in September 1942 with a dozen others in their shelter, even though nearby shelters were raided; except for Sheva’s family and a few hundred other Jews in hiding, the ghetto was again emptied and the victims sent to Bełżec. Then Sheva’s plans to escape the ghetto were realized; a Polish woman she had known from from before the war gave Sheva her own birth certificate to serve for a false passport; Sheva would now be known as Hanka Buczek. Then she had an opportunity to travel hidden in the wagon of the Krupka family of Rohatyn, who were moving to Brody. She left on the night of her 26th birthday, with a gift from her mother of her father’s gold watch and a few other precious items. She never saw Rohatyn again.

In Brody she worked for the Krupkas, as their household servant “Hania” (Hanka). At first she was stricken by typhus and the Krupkas had to nurse her through the fever back to health; she also had rashes and swelling in her legs which persisted for the next years. Sheva was aware that her presence in Mr. Krupka’s house was “like having a bomb that could explode any day and wipe out his entire family”. Other members of the Krupka family visiting Brody from Rohatyn knew Sheva and helped her maintain her false identity, but harboring a Jew was a capital crime in the General Government. Then the aktions and liquidation of the Jewish ghetto began in Brody, and it was no longer safe for Sheva to remain there; in May 1943 she left for Lemberg with her false papers in hopes of getting a work card from the German administration.

Sheva’s attempts to find work in Lemberg failed because she lacked the necessary work cards and history. She resolved to leave occupied Poland for work in Germany, still disguised as a Pole; many young Polish and Ukrainian women were captured and forced to work in Germany for low wages. Her problem was how to register for that work voluntarily without being suspected as a Jew, since no Poles or Ukrainians volunteered. Eventually she was sheltered and aided for ten days at the infamous Janowska labor and transit camp adjacent to the ghetto in Lemberg by a Polish doctor there who recognized the danger of her situation. Before departing Lemberg she was stripped of her remaining valuables by guards at the camp.

By train Sheva traveled with other workers to Vienna, where she worked for a brief time in a restaurant kitchen before moving on to Stuttgart. There she found work at an Evangelical religious hospital, the Bethesda Krankenhaus, cleaning the medical wards and assisting patients. She was still in disguise and had to scrupulously guard her true identity, but for the first time she was in relative safety compared to occupied Poland; the primarily German administrators of the hospital were kind to her, and her mostly foreign coworkers provided some companionship. Registered for work as a Pole by the local Gestapo, she had to wear a letter “P” on all of clothing when in public; the registrar explained it was because Poland had resisted German occupation, so her freedoms were restricted in town. In the only package she received from Poland there was a coded letter which revealed that her entire family had died in Rohatyn; later she would learn they were victims of the June 1943 ghetto liquidation.

The war reached Stuttgart, including frequent air raids in 1944. Resistance efforts also swelled, and Sheva was attached to the periphery of a Czech network working to undermine the German war effort through theft and distribution of weapons; the group included one of her co-workers at the hospital and others in the city. A bombing raid destroyed the workers’ residence but left the hospital intact, although without electricity. In a subsequent bombing, Sheva was injured when a portion of the building she hid in was damaged.

During this instability, by chance Sheva met two other young Jewish women who had escaped the Rohatyn ghetto a few weeks before her, now living in Stuttgart as foreign workers like herself. They could not meet often because of the risk of detection as Jews, but the knowledge that there were others in her situation was comforting to her.

The war’s end came quickly; following another bombing, the shelter where the hospital staff and patients went for protection was opened by French soldiers, the first wave of Allied forces to reach their location. The soldiers needed doctors to aid the wounded, and with the German surrender and Allied occupation that came soon after, Sheva could finally reveal her identity to the astonished hospital staff. With no home to return to, Sheva and the other women from Rohatyn each elected to emigrate; one left quickly with a cousin in the French army and then on to America; the other married an American officer in Stuttgart and traveled to the US with him. Sheva received a letter from the Krupkas, and met with them soon after; they had evaded the advancing Soviet army in Brody by traveling to Munich, and were now homeless like most others.

While looking for options to emigrate and start a new life, at a displaced persons camp in Stuttgart Sheva met the man who would later become her husband. Israel Lederman, a native of Łódź, was a survivor of several concentration camps, including Auschwitz and Dachau, and had lost his wife and child along with his brothers and the rest of his family. After a brief courtship the pair married, and with the assistance of the local DP camp, HIAS and the Joint Distribution Committee, they were able to emigrate to New York in June 1946.

Sheva, now going by Sylvia, lived with her husband in Queens and worked in the garment industry for many years after the war. The Ledermans hosted the Krupka family on their visit to the US in 1966. Sylvia maintained correspondence with other émigrés from Rohatyn, and participated in Rohatyn Society functions in the US. In retirement, she continued to work on her memoir; the book was published posthumously, after her passing in 2008. Her photographs, notes, and other items were donated to YIVO in New York.

Elements of the Memoir with Value to Rohatyn Studies

Portions of Sheva’s recollections of her life in Rohatyn during the war have already been summarized above. Many additional details in the memoir will be of interest to researchers studying the history of Rohatyn and of the Holocaust in eastern Poland. A few excerpts will help to illustrate the kinds of details available in the book.

Two paragraphs from the 20 March 1942 aktion:

We could hear shots outside, not far away, though we were far from the ghetto. I wondered why the sounds carried so far… The man said, ‘Perhaps I should not tell you this, but for the past several weeks the Germans have ordered trenches to be dug nearby, behind a brick factory. The Jews themselves had to dig these trenches, never guessing it would be for their graves. All the Jews had been taken there from the ghetto, and they are now being shot and thrown into the trenches.

Now I recalled that for the past several weeks they had rounded up the men from the ghetto to do forced labor, to dig trenches. No one knew for what purpose, but no one thought it would be for themselves. There were many rumors; some said it was to make foundations for a new brick factory; others supposed that the trenches would serve to offset attacks if the Russians returned.

The next day, Sheva heard from a farmer’s wife:

She told me that last night some neighbors had come by and had told them that nearly three thousand people had been shot in the hours from morning until about four in the afternoon. They had heard moans and cries from the pits. The people were first stripped naked and then thrown into the pits, dead or still half-alive.

And from the farmer, after it was confirmed that the Gestapo had left:

He said that in the pits nearby there were nearly three thousand dead bodies, left where they had been shot yesterday. The Gestapo had done its work and had not even bothered to cover the pits.

When Sheva returned to the ghetto, she heard from a neighbor who lived in her same house, Tyla Nemeth:

In a few words she told me that her father had been rounded up with the others in the marketplace, brought to the pits, stripped naked, shot, and thrown into the mass grave. During the night, when all was quiet, he had summoned the last remnants of his strength and had thrown off the corpses that had fallen on top of him in the pit. Then, naked as he was, he had run to the nearest house for shelter. The Gentile owner of that house had taken pity on him. In the morning he had gone to the ghetto to let the Nemeth family know that he was alive and that they should bring him some clothes.

Later in the same chapter:

Our neighbor, Yoyne Nemeth, gave us a clear picture of how the people had been gathered in the marketplace, loaded on trucks, and taken to the common graves to be shot. They had been packed so tightly that many had panicked, lost their senses, and began to laugh hysterically, screaming and tearing their hair. Many perished before they got the place of execution.

For those studying family histories of Rohatyn (Jewish, Ukrainian, and Polish), the memoir provides a large number of names with characteristics and circumstances. Several of the local people who aided Sheva are already named above. In addition, the book names several of her Jewish family and friends in the ghetto and beyond; beyond those already named here, some are: her uncle Hirsch Weiner, his wife Ryfka, son Chaim, and daughter Glickel; the Weiners’ son-in-law Shloma Handschau and his sons Nuchem and Yudah; Sheva’s Aunt Sara; Izio Horn, a student of Sheva’s and who worked in his father’s bakery in Rohatyn; her friend Liba Teichman; the attorney Dr. Freiwald; her uncle Mendel Weiler; Rohatyn’s chief Rabbi Tumin; aktion victims with family names Margulies, Huter, and Felker; her friends from Rohatyn in Stuttgart, Pepa Kleinwaks amd Bluma Wildman; Max (Mayer) Altman (who had left for the US before the war) and his daughter Klara Altman; and Dr. Isaac Lewenter in the US.

Additional References

Most of the information presented here is taken directly from Lederman’s published memoir. Additional biographical details are from research by Dr. Alex Feller for the Rohatyn District Research Group (RDRG).

Two brief excerpts of Lederman’s survival story also appear in the Rohatyn Yizkor Book: “A Jewish Girl’s Road to Hell” [p.239 of the Hebrew/Yiddish section] and “The Death of Chaimke” [p.32 of the English section]. These texts also appear in updated form in Leah Zahav’s “Remembering Rohatyn” [p.311 and p.428]. This latter text includes additional information about other Weiler relatives in the ghetto, including the Blotners.

An additional brief biography of Sylvia Lederman by Leah Zahav was included in “Remembering Rohatyn”, with further information about other family connections including Anna Kornbluh and Dov Schmorak.

This page is part of a series on memoirs of Jewish life in Rohatyn, a component of our history of the Jewish community of Rohatyn.