![]() Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

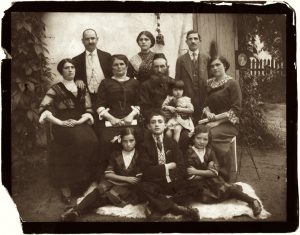

Studio portrait of a Jewish family in Drohobych, ca. 1910~1920. From the USHMM collection.

Jews are an ethno-religious group, with strong interrelationships between their ethnicity, nationhood and religion. Although a very small percentage of the global population, Jews are widespread as a minority in many countries on most continents. Terms for others to identify and communicate with Jews are needed in more than a hundred languages. Because of the link many Jews make between their religion and their ethnicity, terms in many languages blur the distinction as well.

In English, an ethnonym is a name used to identify an ethnic group. Names for ethic groups may be created and used by others (exonym) or may be self-designations used by the ethnic group itself (autonym or endonym). As an exonym example, in English, members of the largest ethnic group in the state of Germany are called Germans, and in Ukrainian they are called Німці (Nimtsi); ethnically-German people refer to themselves with the endonym Deutsche.

The English term Jew is preferred by Jews in its use as a noun to identify themselves, but it is considered offensive when used as an adjective (“a Jew banker”). Instead, the term Jewish is preferred for adjectives. To keep the distinction clear, English-speaking Jews usually avoid the constructions “a Jewish person” or “a woman of the Jewish faith”. Context usually makes clear whether others intend Jew and Jewish in a neutral sense.

Hebrew-speaking Jews refer to themselves by a number of terms; a common set is יהודי (Yehudi, masculine singular), יהודיה (Yehudia, feminine singular), יהודים (Yehudim, plural). The German-language word Juden is derived from the Hebrew.

In Ukraine, there are regional differences in terminology for Jews which can lead to misunderstanding. Today the preferred terms in the Ukrainian language are Єврей (Yevrey, singular) and Євреї (Yevreyi, plural). In Russian, the terms are Еврей (Yevrey, singular) and Евреи (Yevrei, plural).

A still image of Jews in Rohatyn, from a 1930s holiday film by Fanny Holtzmann. Free access courtesy Edward M. Holtzmann and YIVO Archives and Library Collections.

Click the image to see the video.

In western Ukraine, especially in the former Austrian imperial crownland of Galicia where Rohatyn is located, “Єврей” may sound foreign to some older people, as an import from the former Russian Empire and a term imposed through Russification of Ukraine, especially during the Soviet period. Traditionally the Ukrainian language had only the terms Жид (Zhyd, singular) and Жиди (Zhydy, plural) to describe Jews; the words were normal and neutral in Ukrainian under the Austrian Empire in Galicia and in the same areas in the interwar period under Polish rule. Influential writers in the modern literary Ukrainian language (Taras Shevchenko, Lesia Ukrainka, and others) used the terms in their works.

The historical tradition in Ukrainian is phonetically similar to words in other Slavic languages in countries bordering western Ukraine. In Polish, Żyd (singular) and Żydzi/Żydowie (plural) are neutral or respectful. The same term in Czech and Slovak is Žid. Even in Hungary, another border country but with a much different language history, the neutral term is Zsidó.

Friction arises when traditional Ukrainian encounters Russian in speech and in print; this conflict has been active since the mid-19th century when the Ukrainian language was being revived and modernized among the ethnic identity movements across Europe. In Russian, the word жид (zhid) is spelled the same as the Ukrainian word, but Russian speakers consider the term pejorative in any context. The word was shunned in Ukraine under the Russian Empire, and outlawed in Ukraine in the 1930s under the Soviet Union. Decades of Russian language dominance in Ukraine have left a very strong connotation that жид is a harsh slur, regardless of the language tradition and intent of the speaker. Misunderstandings over the word continue to spark public conflicts in regional and international news.

Although Єврей and Євреї are imported words in Ukrainian, they are now in very common usage in Ukraine as neutral terms for Jews. Importantly, these terms are not prone to misinterpretation and misunderstanding of intent. Thus, today the recommendation by Jews and others working on Ukrainian-Jewish relations across Ukraine is to use only Єврей and Євреї going forward.

Researchers using older books and records may encounter a variety of other terms for Jews. In English, the terms Hebrews and Israelites are archaic now as broad labels for Jews, but both were once common; today the terms often refer to early or biblical Jews, but there are other uses as well. In western Ukraine, historical administrative and vital records from the Austrian period may use the terms Mosaische (for the religion), or Israelitische (for a community), but the Polish term żydowski was also used then and continued to WWII. Of course one will also find the terms Жид and Жиди in Ukrainian literature of the recent to distant past; on most cases context will be required to understand whether neutral or negative value was intended.

The Jewish musicians “Pushkin Klezmer Band” perform at Euromaidan in Kyiv, 23Dec2013. See also the article on Jews at Maidan in Tablet Magazine, 25Feb2014.

Issues of and conflict over the neutrality of terms for people and places are common everywhere, and acceptable/preferred terms can change over time. An example is the English word for the state of Ukraine; for most of the 20th century, English-language sources typically referred to the country as “the Ukraine”, but since independence in 1991, Ukrainian government publications in English have used “Ukraine” without the article (unlike “the Netherlands”, another state with a name derived from a descriptive land term); English-language sources elsewhere now follow their lead. Where the transition lags, residual use of the article can be perceived by some as insulting, even where no offense is intended.

In an article listing Jewish ethnonyms on English Wikipedia accessed on 07Jan2017, which itemizes terms used by language without reference to regional variations, the preferred Russian terms are correctly listed. The same article currently gives only two terms in Ukrainian (Жид and Жиди), which reflects only the traditional/archaic usage, and could be offensive to Jews and others from all of Ukraine. The same page on Ukrainian Wikipedia includes both Єврей/євреї and жид as neutral terms in the Ukrainian language, as does the page on Russian Wikipedia. More than for most of the languages listed in those articles, the Ukrainian terms need footnoting to provide the language and political history, and the opposed meanings of some of the terms in modern Ukraine. Context like this is difficult to include in a tabulated article of this type; other articles on Wikipedia are probably needed to adequately develop the topic.

Sources

Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-existence; Paul Robert Magocsi and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern; University of Toronto Press; Toronto, 2016; p. 7.

Rabbi Moyshe Leib Kolesnik; personal communication, 04Jan2017.

The Sion-Osnova Controversy of 1861-1862; Roman Serbyn; in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective (Third Edition); Peter J. Potichnyi and Howard Aster, eds.; Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies (CIUS) Press; Edmonton-Toronto, 2010. Available on the Internet Archive.

Wikipedia in English: articles on Ethnonym; Exonym and endonym; Jews; Jew (word); Jewish ethnonyms; Ukraine; Russification of Ukraine; Zhydovka

Wikipedia in Ukrainian: articles on Євреї; Етноніми євреїв; Україна; Русифікація України

Jewish Encyclopedia; Isadore Singer, ed.; Funk & Wagnalls Co.; New York, 1901-1906; online edition: article on Jew (the Word)

Reclaiming ‘Jew’; Mark Oppenheimer; in The New York Times; New York, 22Apr2017.