![]() Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Toward the end of the 19th century, the Austrian Empire was cracking apart under the pressure of economic inequality and growing national and ethnic conflicts; in Galicia, the pressure was severe. At the same time the minority Jewish community of Galicia was beginning to organize to push for political representation, several different philosophies split the Jewish efforts and worked against the unity needed for progress. The complex and changing Galician story is well documented in academic books and articles [1] [2]; key studies provided most of context for this article. The local situation in Rohatyn is highlighted further in additional sources, which show how bizarre (and unlawful) the situation had become in and around Rohatyn by 1907; those events also featured a joint effort by Jews and Ukrainians (Ruthenians) to improve their standing in the Austrian parliament.

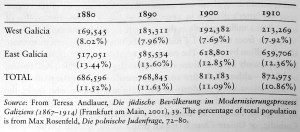

Jewish population of Galicia by census year [from 1: p18].

The majority populations of Galicia as a whole, in roughly equal numbers, were Poles and Ukrainians; Poles dominated in the west and Ukrainians in the east, but with significantly unequal economic and political power which, with the support of the Austrian government, favored the landowning Poles [2: p.149~150]. Polish politicians were able to exercise power in the Austrian Parliament, control the Galician Sejm and the important district councils, thanks to peculiarities of the Austrian electoral system, their use of the Jewish minority, and the influence of eastern landowners who held vast tracts of land on which peasants lived in poverty [2: p.151]. Austrian voting power was significantly disproportional in general, both by wealth and by urban/rural differences; in Galicia, it took almost seven times as many Ukrainian votes as Polish votes to elect a deputy to parliament, and already in 1892, Ukrainian delegates to the Austrian Parliament protested against election fixing and terror tactics at voting stations [2: p.152~153].

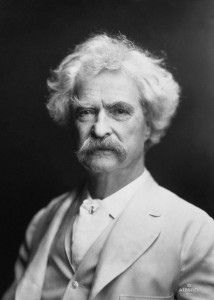

Mark Twain in 1907. Photo by A. F. Bradley. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Things were little better within the parliament house itself. The American author and humorist Mark Twain sat in on a parliamentary session in Vienna in late 1897 and wrote a serious but astonished 11-page article about his experience for Harper’s Magazine, describing scenes of riot, racial slurs and other foul language, and manipulation of parliamentary procedure to favor the majority parties [6]. In a second article published in the same magazine in 1899, “Concerning the Jews“, Twain quotes a reader who writes to him asking why Jews were blamed for much of the ruckus Twain had seen in Vienna:

“The show of military force in the Austrian Parliament, which precipitated the riots, was not introduced by any Jew. No Jew was a member of that body. No Jewish question was involved […]. No Jew was insulting anybody. In short, no Jew was doing any mischief toward anybody whatsoever. In fact, the Jews were the only ones of the nineteen different races of Austria which did not have a party – they are absolutely non-participants.” [7: p.527]

And then Twain reports the reticence of many Jews to participate in the political process at all:

“It was a pathetic tale that was told by a poor Jew in Galicia a fortnight ago during the riots, after he had been raided by the Christian peasantry and despoiled of everything he had. He said his vote was of no value to him, and he wished he could be excused from casting it, for indeed casting it was a sure damage to him, since no matter which party he voted for, the other party would come straight and take its revenge out of him. Nine percent of the population of the empire, these Jews, and apparently they cannot put a plank into any candidate’s platform!” [7: p.534]

But indeed the Jewish vote was becoming a small but important component of imperial elections. Already by the early 1890s, a populist nationalist press began publishing in Yiddish in Galicia, and became a theater for discussion, argument, and propaganda within the Jewish community [1: p.109~112]. A new Jewish National Party formed in 1893, without reference to the Zionist sentiment which had started it but with a call for Jewish non-orthodox education, political equality, and national unity [1: p.96~102]; both unity and nation recognition were slow to develop. Continuing nationalist unrest at the turn of the century and the Russian revolution of 1905 sufficiently frightened the Austrian emperor to concede to the empire’s proletariat their principal demand: universal (male) suffrage [1: p.201]. Implementation was not immediate and fell far short of the intended equality. Jews, still not considered a nationality in the Empire, realized they needed national recognition in order to benefit from wrinkles in the new electoral law [1: p.202]. Others realized this also, and then things got interesting.

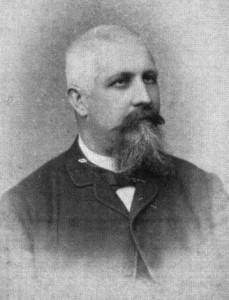

Yulian Romanczhuk. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Yulian Romanchuk, born in the village of Krylos (40km south of Rohatyn), a teacher and journalist and at the time the head of the Ukrainian National Democratic Party (one of several ethnic National Democratic parties) in Vienna, raised the topic of national recognition for Austrian Jews in a speech to Parliament on 1 December 1905, and demanded that Jews be recognized as a Volksstamm (literally tribe, or nationality), independent of language and religion [1: p.201~203]. This act was the first visible evidence of cooperation on election reform and mutual support between Ukrainian and Jewish legislators in Vienna, but it was followed by more action at both imperial and grassroots levels, in towns and cities all over eastern Galicia. In early 1906, Jews and Ukrainians jointly planned and spoke at a cooperative meeting of 5,000 people in Zavaliv (50km from Rohatyn) on the subject of voting reform; in April 1907, a leader of the Jewish National Party editorialized in the Ukrainian daily paper Dilo that Jews who self-identified as Poles and profited from their association with the Polish nobility should be opposed, and that “together with the Ruthenians and the patriotic Polish elements we want to end this oligarchy” [1: p.260~261]. The buildup to the May 1907 parliamentary election was electrically charged.

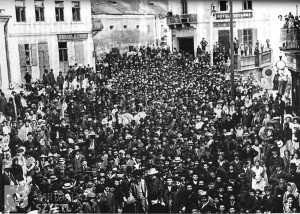

The Jewish political rally in Buczacz, 1907. Source: Virtual Shtetl.

At the same time the tensions were dividing Jews along some political lines, in other areas Jews were modernizing and coming together as never before, uniting with a common sense of national community, at least among Galician Jews [1: p.240]. Political rallies in particular attracted Jews from all classes, men and women, young and old, religious and secular. A remarkable 1907 photograph of a mass rally in Buczacz to support the Jewish national candidate Nathan Birnbaum shows a crowd of unusually mixed people for the period, including women and children standing next to men, and modern women with uncovered heads beside traditional women with wigs [1: p.240~242] [8]. The Jewish writer S. Y. Agnon attended the rally in his home town as a teenager; he would later write about the conflict between traditional Jewish life and the modern world, including in his comic novel The Bridal Canopy (half of which takes place in Rohatyn), and would eventually win the Nobel Prize for Literature.

For the perspective from Rohatyn on the election as it finally played out, we turn to an article written by Dr. N. M. Gelber for the Rohatyn Yizkor book [3: p.62~63]. The language of the article plainly expresses the outrage felt by Rohatyn citizens at overt election manipulation:

“The Jewish community played an important role in the election campaign to the Austrian parliament. In 1907 the Viennese parliament passed a law eliminating the system of constituencies, and suffrage was granted to all citizens of the empire. This act aroused new hopes and possibilities among the Jews in Galicia. In the Zionist camp, preparations on a large scale began for the elections that took place between 17 and 27 May 1907. Election publicity was organized throughout Galicia that was also geared toward realizing Zionist ideals. Wherever there was a Jewish community, candidates were nominated. Gatherings were held, speeches were made; preachers and rabbis and just ordinary Jews aroused the masses from their political lethargy and brought into the darkened streets of Galicia light, national hope, and political clarification.

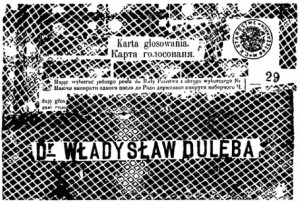

Ballot card in Polish and Ukrainian: “Being entitled to vote for one representative to the state parliament from District 29, I give my vote to Dr. Władysław Dułęba”. Source: Rohatyn Yizkor book, page 62.

Rohatyn belonged to the 29th election district, which encompassed the municipal areas of Brzeżany, Rohatyn, Chodórow, and Brzozdowce. The Zionist organization of the district nominated the well-known Zionist leader Rabbi Dr. Shmuel Rappaport. The Polish choice for nominee to the Austrian parliament was Dr. Wladyslaw Dulemba [Władysław Dułęba], who was nominated by dint of terror, bribery, and fraud. He had been the representative for the district in 1902. Dulemba was backed by assimilationists but also received aid from the court of the Admor (rabbi and spiritual leader) of Belz. The Admor ordered his Hasidim [pious followers] not to vote for the Zionist, Rabbi Dr. Shmuel Rappaport, but to vote for the Pole Dr. Dulemba who, as it was known, was one of the leaders of the [Polish] National Democrats [Endecja].

The Jewish national election committee of Rohatyn was headed by Dr. Katz, Dr. Moritz Fichmann, Marcus Weiler, A. H. Holder, and Dr. Oswald Klugman. Right from the beginning, the Poles, with the backing of the Austrian government, waged a tyrannical election campaign that became worse on Election Day. The campaigners for Dr. Dulemba paid five crowns for each vote. The Jews were not given ballot slips, and the head of the district, as well as the mayor, distributed ballots with the name of Dr. Dulemba – all this with the backing of the Austrian government. On Election Day the police stood in front of the election hall, and anyone who did not present a ballot with the name of Dr. Dulemba was not permitted to enter.

Despite the terror, stealing of ballots, and bribe money, Dulemba was unable to obtain a majority in the first round and was forced to run again, against Dr. Rappaport. In the second round, which took place 31 May, the Ruthenians decided to vote for Dr. Rappaport. On Election Day the terror was increased even more. Contrary to election laws, government officials together with the head of the district and the mayor openly carried out acts of bribery and deceit with threats of pogroms against the Jews. Ballots marked Dr. Rappaport were stolen out of the ballot box, and in this way, Dr. Rappaport lost, and Dulemba was elected.

The election committees of the Zionists and Ruthenians presented an appeal to the parliament contesting the election – however, to no avail.”

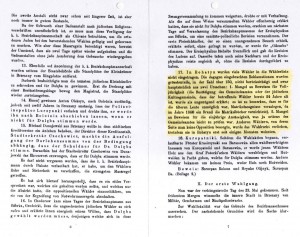

Protest filed with Austrian authorities against election violations in Rohatyn. Source: Bavarian State Archives.

The RDRG located a copy of that protest, probably authored by Nathan Birnbaum, preserved in the Bavarian State Archives [4]. The text of the protest filed with the Austrian authorities includes this damning paragraph 17, translated from German for the RDRG by Edgar Hauster:

“In Rohatyn many voters were not endorsed in the voters listing. The complaints against this procedure, more than 150, were not considered, mainly on these reasons:

1. Lack of evidence for the legal age (confirmation by the Town Hall or the Jewish Religious Community, stating that the respective voter is aged at least 24 years, was declared as being insufficient; the point has to be made that elder people could not present metrical certificates, as the metrical books were destroyed in the year 1860 by fire).

2. Lack of evidence for the residence for one year, which could be proved easily by the Town Hall.

Other voters, not suspected as being oppositional, got the voting rights, although they had lived in Rohatyn for just a few months.”

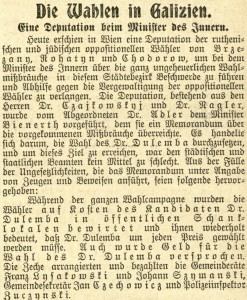

Arbeiter-Zeitung of 29 May 1907. Source: ANNO – Austrian Newspapers Online.

The dispute was covered in the press as well, even at the imperial level. Vienna’s Social Democratic Arbeiter-Zeitung workers’ daily newspaper gave more than two-thirds of a page to detail the complaint in their edition of 29 May 1907. The headline said “Election in Galicia” but the news was all about Dr. Dulemba and the protest filed with Austrian ministers. The newspaper tells that a combined Ruthenian/Jewish delegation formed by Dr. Szajkowskyj and Dr. Nagler, representing the opposition movement from Brzeżany, Rohatyn and Chodorów, was received in in Vienna in audience by minister Bienerth and representative Dr. Adler. The delegation handed to the minister a protest memorandum, comprehensively substantiated by witnesses and evidence; most of the newspaper article is composed of selections from the many problems itemized in the protest. At the end of the audience, the delegation presented the following demand note of 5 points:

1. Replacement of the election commission by a new one formed by representatives of all electable parties.

2. Participation of the representatives at the election process.

3. Exclusion of unathorized persons from the vote count.

4. Delivery of the BLANK ballots 48 hours prior the election.

5. Implementation of the elections at at least two different locations.

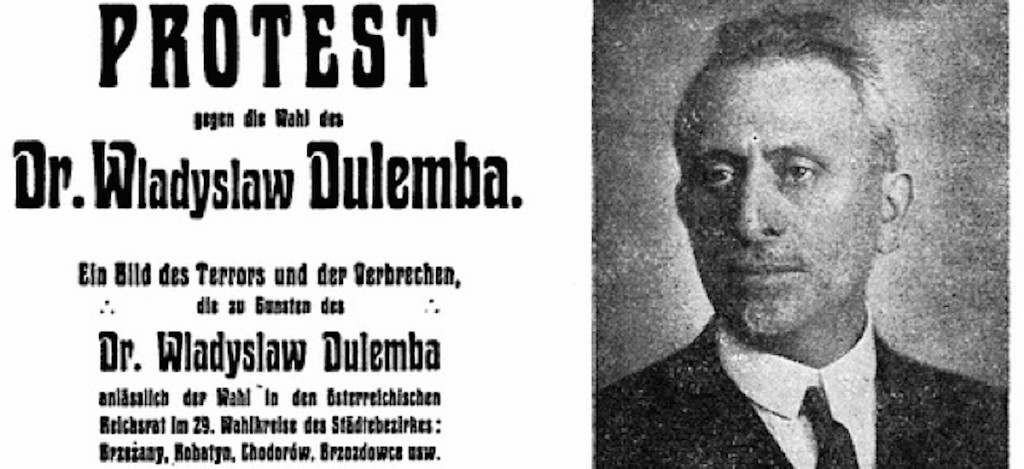

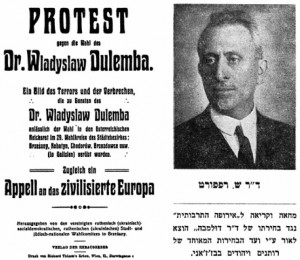

Protest against the election of Dr. Władysław Dułęba, with a photo of opposition candidate Dr. Shmuel Rappaport. Source: Rohatyn Yizkor book, page 63.

Protests were also publicized locally, as in this poster in both German and Yiddish with a picture of Dr. Rappaport, translated as:

“Protest against the election of Dr. Wladyslaw Dulemba. A picture of the terrorism and crimes committed in favor of Dr. Wladyslaw Dulemba in connection with the elections to the Austrian parliament from the 29th Electoral Circuit in the district towns of Brzeżany, Rohatyn, Chodórow, Brzozdowce, etc. At the same time we appeal to civilized Europe. Issued by the United Ruthenian Social Democrats, Ruthenian town and Jewish-National Election Committees in Brzeżany. Publisher – Richard Timm’s Family Press, Vienna II, Darwin Street.” [3: p.63]

The Yizkor book history continues:

“The Polish club, backers of the members of the national government, saw to it that the election of their candidate, Dr. Dulemba, would be accepted.

In the elections of 1911 the Jewish nominee for Rohatyn was the lawyer Dr. Horowitz of Stanisławów, and his campaign was waged by the Austrian member of parliament Ernest Breiter, a gentile who was pro-Zionist, and again, the Jews lost.”

In 1907, the experience in Rohatyn’s District 29 was not unique. In Buczacz, Birnbaum lost the election in part because Ukrainians who wished to vote for him were ejected from the polls [2: p.175]. In Stanisławów, 156 votes for the Jewish candidate Mordechai Braude were disqualified because voters spelled his first name “Marcus” instead of the “Markus” he had registered under; Braude lost the runoff by 123 votes [1: p.270]. In Kolomea, a city where more than half the population was Jewish, thousands of Jews were unable to vote because voter registration was held on a Saturday, and many Jews were unwilling to violate the Sabbath by signing their names that day [1: p.268].

Dr. Dulemba in uniform in 1909. Source: ANNO – Austrian Newspapers Online.

Excerpt from the Wiener Salonblatt 03Apr1909. Source: ANNO – Austrian Newspapers Online.

Despite the threats, violence, and other crimes, some progress was made in the lead-up to the 1907 elections in Galicia, and through the vote: universal male suffrage, the beginnings of a Jewish bloc vote, and cooperation between Jewish and Ukrainian political elements for mutual benefit [2: p.177]. While four to six Jewish legislators had seats in the Austrian Parliament between 1873 and 1906, none represented a Jewish party (most were members of the Polish Club); in 1907, there were candidates representing four different Jewish parties, and three Jewish candidates were elected to the Parliament in the new Jewish Club (along with one Independent, two Social Democrats, and four in the Polish Club) [1: p.287~292]. The Austrian Empire would fall apart just a few years later, but the social and political evolution of Jews in Rohatyn and the region had changed for good.

And Dr. Dulemba? He seems to have survived not only the election runoff, but also the post-election protest, the lurid news coverage, and the local agitation against him and his methods. In fact his career seemed to blossom: in the 03 April 1909 edition of the Wiener Salonblatt, a kind of cultural newspaper covering the social and cultural scene in the Empire’s capital, we find a photo of Dr. Dulemba and a short note that he has been appointed Austrian minister without portfolio, an honorary post with few or no responsibilities. The newspaper congratulates this “gifted politician” and lawyer for his strong and steady rise in politics, and in particular for his contributions to election reform in 1906…

Sources

[1] Diaspora Nationalism and Jewish Identity in Habsburg Galicia; Joshua Shanes; Cambridge University Press; 2014. ISBN: 978-1-10-767489-9.

[2] The Rise of Jewish National Politics in Galicia, 1905~1907; Leila P. Everett; in Nationbuilding and the Politics of Nationalism: Essays on Austrian Galicia; Andrei S. Markovits and Frank E Sysyn, eds.; Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA, USA; 1982. ISBN 0-674-603-12-5.

[3] Yizkor Book for Rohatyn: The Community of Rohatyn and Environs (Kehilat Rohatyn v’hasviva); eds. M. Amitai, David Stockfish, and Shmuel Bari; Rohatyn Association of Israel, 1962 (in Hebrew). Online image version hosted by the New York Public Library. Online English version hosted by JewishGen, coordinated by Michael J. Bohnen and Donia Gold Shwarzstein.

[4] Bavarian State Archives: record Austr.5363.m

[5] Special Orts-Repertorium von Galizien; Verlag der K. K. Statistischen Central-Commission; Vienna, 1886 [the Galician census of 1880, organized by place].

[6] Stirring Times in Austria; Mark Twain; in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine; March, 1898; p.530~540.

[7] Concerning the Jews; Mark Twain; in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine; September, 1899; p.527~535.

[8] Between Austria and Galicia: Jewish Nationalism and Diversity; Joshua Shanes; in Tradition and its Discontents: Jewish History and Culture in Eastern Europe; An Online Exhibition from the Center for Advanced Judaic Studies 2002-2003 Fellows at the University of Pennsylvania.

We thank Edgar Hauster and Dr. Joshua Shanes for their assistance with this article.