![]() Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

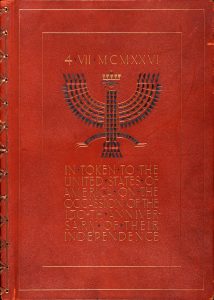

The cover of Volume 1 of the LoC collection.

In 1926, Rohatyn primary and secondary schools participated in a Polish state program modeled on the long-standing Polish custom of students presenting a księga pamiątkowa (a memory book or album) to their teachers, with the pages containing the students’ signatures, and often a poem or other expression of their affection. But this time the custom was expanded and elevated to involve the entire country, and with an extraordinary object: to send a an “emblem of good will” and a message of “admiration and friendship” to the United States of America on the occasion of its 150 years of independence.

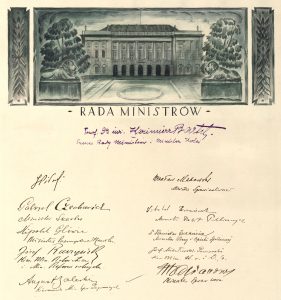

Signatures of the Cabinet of Ministers, from Volume 1 of the LoC collection. Józef Piłsudski is at the top of the left column.

The effort was staggering in scope and accomplishment. Eight months in development, it involved not only schools all over the country, but social and business organizations, religious authorities, plus all branches and administrative departments of regional and national government, all the way up to the Senate, the Sejm, the cabinet of ministers, the prime minister, and the president. More than 5 million Polish citizens (a sixth of the population of Poland at the time) signed the more than 30,000 pages of the declaration, which were collected and bound into more than 100 volumes for delivery to US president Calvin Coolidge on 14 October 1926, to commemorate the US independence sesquicentennial on 04 July of that year. The gift was accompanied by a gold medallion designed and fabricated for the occasion.

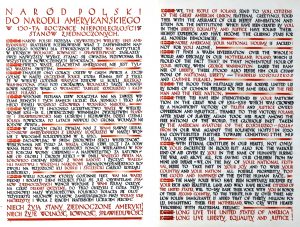

The declaration in Polish and English, from Volume 1 of the LoC collection.

In addition to the millions of signatures, some pages include attractive graphic work, watercolor paintings, even dried flowers. Common artistic themes included symbols of freedom, Polish and American allegorical figures, the buildings which housed the government and business offices of the signatories, and simple or elaborate geometric and floral designs. Apart from educational, religious, and government institutions, the selection criteria for other organizations is not clear; together among pages from the Polish National Organization for Women and the Polish Red Cross are the Intelligentsia Assistance Society, the Municipal Warehouse Authority of Warsaw, the Warsaw Rowing Society, the Institute for Scientific Management, and the Anti-Bolshevik League in Warsaw. All of the volumes of the declaration have been digitized in recent years and made available on the website of the US Library of Congress.

Schools in the Rohatyn district participated as enthusiastically as others in Poland; more than 70 towns and villages in the district are represented on the pages. And on nearly every page are the signatures of students (and often the teachers) at the schools, a singular treasure and a memento of the diversity of the youth of Rohatyn and other settlements in the area during the interwar period.

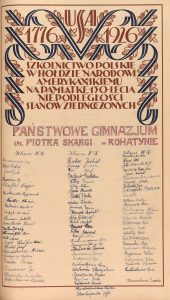

First page of the Piotr Skarga High School in Rohatyn, from Volume 11 of the LoC collection.

Rohatyn’s Piotr Skarga high school (known locally as “the Red School” for its red brick facade, and today as School #2) spans four pages (beginning with image 361) of Volume 11. One can see that the students were a little confused about how to organize their signatures onto the pages; nothing like this had ever been done before. The names will be familiar to anyone researching Jewish Rohatyn: Schumer, Bratspies, Baumrind, Kartin, Weiss, Kreisler, Bussgang, Faust, Teichmann, Liebling, Willig, Reiss, Weissbraun, Rothen, Bohnen, Dub, Halpern, Wald, and many others. There are also many Polish names, including Lewicki. The Polish students seemed to have a particular flair in their signatures; curiously, the names of the Polish teachers are rather difficult to decipher.

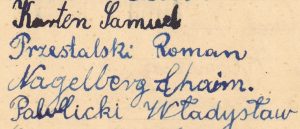

Classmates Samuel Karten, Roman Przestalski, Chaim Nagelberg, and Władysław Pawlicki in Class II at Rohatyn’s boys’ school.

The Library of Congress completed digitization of the many volumes of primary school pages in summer 2017, thanks to funding by the Polish Library in Washington D.C., and all are now available on their website. Volume 70 includes the schools of the Rohatyn district, spanning about 150 pages beginning with the seven classes of Rohatyn’s own girls’ school on image 55. Here, some of the names are written by the head teacher (which helps their clarity on the pages), but most, especially in the smaller villages, are signed by the young students themselves. Many of the same names from the secondary school list appear again in the Rohatyn girls’ and boys’ primary schools, with more names including Allerhand, Schächter, Hammer, Lewenter, Kleinwachs, Hornstein, Glotzer, Reichbach, Goldschlag, Fuchs, Amarant, Kimmel, Nagelberg, Fruchter, Wind, Schnee, Brandwein, Kirschen, Freiwald, and Szkolnik. Spellings of both family and given names vary, among both the Jewish and Polish students. Some of the names are unusual (e.g. Moses Jupiter; another family member’s name, spelled Yupiter, appears elsewhere). A few students with recognizably Ukrainian names appear as well in the Rohatyn school lists (including Worobec, i.e. Vorobets). On the list of teachers for the boy’s school, in addition to Father Michał Struś leading the catechism lessons, there is a Herman Schwarz listed as religion instructor, likely for the school’s Jewish students.

It is no surprise that familiar names also appear on the pages for nearby towns and villages with pre-war Jewish populations, including Żurów (on image 65), Stratyn (image 77), Knihynicze (image 211), Bursztyn (image 167), and Bukaczowce (image 169). Local Ukrainian names are frequent among the student signatures of nearby Czercze (image 165) and Potok (image 97). In Zaluże (image 71), today’s Zaluzhzhia suburb of Rohatyn, one finds more children named Worobec (Vorobets), plus Werbiana/Werbjana (Verbiana); in Wierzbołowce (image 179), today’s Verbylivtsi, one finds many children with the name Skrobacz (Skrobach).

Design from the cover of Volume 70, which includes primary schools in the Rohatyn district.

Despite the huge scope of this endeavor, many Polish schools were not included in the volumes delivered to the United States, for reasons we do not know. Rohatyn’s large Ukrainian high school, which had as students a number of the Jewish children in town, is missing; so is the Hebrew school of Rohatyn and all of its students and teachers.

Librarians at the Library of Congress have written that the volumes in this collection were a “forgotten treasure” until some of them were brought out of storage to celebrate the opening of a new reading room of the European Division of the library in 1997, seventy years after their last public viewing. New interest in the collection prompted the Library to digitize all of the volumes of the collection during the next twenty years, and to make them available for searching and browsing. We agree with the Library that this collection is indeed a gift, even more meaningful now than it was when the American president received it in 1926.

Note: The illustrations on this page are all taken from the Library of Congress digital collections website, linked below. For presentation here, the images have been reduced in resolution, and in some cases cropped. To browse the collection beyond these few images, and to see and/or download images at full resolution, please follow the links in the text and image captions above or the sources below.

Sources:

- “Emblem of Good Will”: A Polish Declaration of Admiration and Friendship for the United States of America; catalog of an exhibition celebrating Poland’s Constitution Day and the opening of the new European Reading Room; Library of Congress; 1997.

- Polish Declarations of Admiration and Friendship for the United States: Finding Aids; United States Library of Congress. See also the valuable description and context in the “About this Collection” summary by the Library and this 2017 Library news article, as well as this index to the volumes, and this complete inventory of place names in the primary schools volumes.

- Polish Declarations of Admiration and Friendship for the United States: Secondary schools; Volume 11; 1926; United States Library of Congress, MSS36483.

- Polish Declarations of Admiration and Friendship for the United States: Grammar and elementary schools; Rawa Ruska ~ Rudki; Volume 70; 1926; United States Library of Congress, MSS36483.

- Polska 1926: Portret Zbiorowy II RP (Poland 1926: A Group Portrait of the Second Republic of Poland) [in Polish]. Offers additional search criteria for investigating the collection, including surnames, a map, and more.