![]() Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

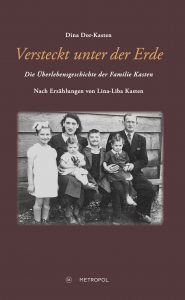

Dina Dor-Kasten; Versteckt unter der Erde – Die Überlebensgeschichte der Familie Kasten (Hidden Under the Earth – The survival story of the Kasten family); translated from Hebrew to German by Eva Tyrell and edited by Ruth Snopkowski for the Gesellschaft zur Förderung jüdischer Kultur und Tradition e.V.; Metropol Verlag; Berlin, 2016.

Introduction

Time and again I asked: How could this happen?

And Mama answered: That’s how it was!

The cover of the book, showing the Kasten family

at the Wegscheid camp in Linz, Austria, in 1947.

This page describes a Holocaust memoir written by Dina Dor-Kasten, who was born in 1940 in Bukaczowce (today Bukachivtsi), a medium-sized town about 25 kilometers (15 miles) southwest of Rohatyn and part of the historical Rohatyn district. After a prologue which explains how the book came about and a brief overview of the political, social, and military processes which drove the World War II genocide in eastern Galicia, the majority of the book presents the story of the Kasten family’s struggle for survival in the voice of Lina-Liba Kasten (née Fuchs), as told to her daughter Dina in letters and in conversations over a period of years after the family had made aliyah to the new state of Israel and Dina had grown to adulthood. A short final section of the book presents Dina Dor-Kasten’s own memories of her early post-war life, beginning just before the family left a DP camp in Austria to travel overland in Europe and then by boat to Israel.

The Rohatyn Yizkor Book and many of the memoirs in our series of reviews include tales of survival during the German occupation of the Rohatyn region, and some such as Jack Glotzer’s memoir I Survived the Holocaust Against All Odds describe extreme difficulties trying to secure shelter against the elements and find food while hiding from potential killers for an entire year. Dor-Kasten’s book tells how the Kastens escaped the Rohatyn ghetto shortly after the first mass-killing aktion to live for more than two years in a deep forest near Bukachivtsi, through their own ingenuity and with the help of a few other Jewish families and individuals in hiding plus a small number of gentiles in nearby villages. No other memoir in the series describes life and death in the forest in such arresting detail.

Working from notes and tape recordings she had made while her mother told her of their family’s early life, Dor-Kasten and her husband further researched the people, places, and events of the time, remembering her mother’s request, “Some time you must write this down.” Together they conducted investigations in archives, reviewed the history in books and other records, and visited and spoke face-to-face with other survivors of the Holocaust in the Rohatyn district now living in Israel and the US. They traveled to Bukachivtsi and Rohatyn in 2001 to speak with residents there, and to stand again in the place where the Kastens had barely survived for more than two years, in the Vytan forest.

Dor-Kasten wrote the original version of the memoir in Hebrew (as כך זה היה, or That’s How it Was), with the names of people outside her family changed for privacy reasons, and she published that version in Israel in 2008; she later revised the memoir to include the real names of others and published that version in 2014. The library at Yad Vashem holds copies of both the 2008 edition and the 2014 edition, and the USHMM also holds copies of the 2008 edition. A friendship between Dor-Kasten’s sister Tonia and Ruth Snopkowski of a Munich-based Jewish culture and tradition society resulted in a translation of the book into German and publication in 2016 (the edition used for this review).

The book in German is still available from the publisher in digital (pdf) format. The paper version of the book is no longer in print but copies are available in libraries in Germany, the United States, and Israel. A few good-quality new old stock and used copies are available from independent booksellers.

This page includes a brief summary of the lives of the Kasten family members before, during, and after the war, plus several details from the memoir with particular value for researchers of the history of the Rohatyn area. As noted below, portions of the book also have significant relevance to researchers of other wartime places and issues, including anti-Jewish aktions, bunkers in ghettos and surrounding forests, and righteous gentiles who risked their lives to aid Jews during the war.

A Brief Summary of the Kasten Family Story

Note: Before World War II the Kasten family lived in multicultural eastern Poland, speaking Yiddish at home but capable of both Polish and Ukrainian as well. Polish spellings of place names were retained in the German edition of the memoir, but are modernized to English-transliterated Ukrainian names on this page for the benefit of modern readers; examples are Bukachivtsi for Bukaczowce, and Vytan for Witan. Yiddish-language personal names, especially pet names for family members, are often rendered in German versions in the book, but several of those are spelled in their English versions here; examples are Shmulik (for Samuel), Yossel (for Josef), and Dudshe (for David).

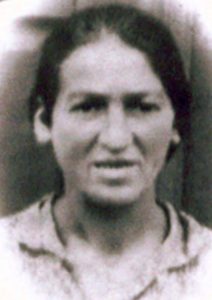

Klara-Chaja Fuchs, Lina-Liba’s mother. Source: Yad Vashem.

Lina-Liba Fuchs was born in 1915 to Klara-Chaja (née Hermann) and Shmuel Fuchs of Perehinske, a town in the Stanisławów voivodeship (Ivano-Frankivsk oblast today) about 70km south of Bukachivtsi and 100km south of Rohatyn. Shmuel died of typhus a few months after Lina was born while serving as a soldier in Albania for Austria-Hungary during World War I. The widowed Klara raised Lina on her own for years, working as a baker for the town’s Jewish community, with help from Lina when she was old enough. When Lina turned 15, Klara remarried and Lina was sent to Stanisławów to get a job, where she enjoyed an independent life for eight years.

Josef Kasten (at #1) with a Jewish youth group in Bukachivtsi, undated. Source: Dina Dor-Kasten via JewishGen.

Josef (Yossel) Kasten was born in Bukachivtsi in 1906 to Etel-Dina (née Mulbegott) and Meir-Hirsch Kasten as the fourth and last child. Yossel’s mother died giving birth to him, and the boy was raised by his grandmother though he remained in close contact with his father and siblings. In the interwar period, more than a third of the population of Bukachivtsi was Jewish; as a young man Yossel proudly joined the Betar movement and dreamed of emigrating to Eretz Yisrael. He became a tailor like his father and in time he established his own independent workshop, employing two others. A serious man, he was respected by the local Ukrainian, Polish, and Jewish communities. Yossel remained a bachelor into his 30s, until his elderly grandmother urged him to marry.

Lina and Yossel met and married in Perehinske in 1938, settling in Bukachivtsi in the house of Yossel’s grandmother where he had grown up. They welcomed a son, Shmuel (named for Lina’s father), in spring 1939, and then a daughter, Etel-Dina (named for Yossel’s mother – she was later the author of the memoir) in 1940, after the German invasion of most of Poland and the Soviet occupation of southeastern Poland (former eastern Galicia).

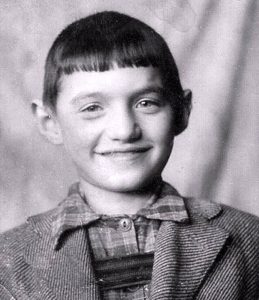

Dina’s brother Shmuel in 1946. Source: Yad Vashem.

Life became difficult and dangerous for the Kastens in July 1941 after the German occupation of Bukachivtsi; here the family’s timeline differs some from the wartime chronology in the “Bukaczowce” chapter of the Pinkas Hakehillot Polin and from testimonies of some other survivors. According to the memoir, the Jewish experience in Bukachivtsi was like a preview of the Rohatyn ghetto, with Jews concentrated in an open ghetto from nearby towns and villages, hunger and disease due to food and medicine shortages, forced labor in farm fields, plus round-ups, deportations, and shootings. Yossel dug a hiding place under the floor in the bedroom of their house, which protected the family from discovery in several small aktions. Some time in the summer of 1941, Yossel and Lina had had a baby boy they called Munyie. In about October 1941, with other Bukachivtsi Jews the Kastens were expelled from their home, which was immediately taken by a Ukrainian neighbor, and they were forced to walk with only a few belongings to the ghetto in Rohatyn; it took a full day and night.

A map from 1930 showing three places in the story: Perehinske, Bukachivtsi, and Rohatyn. Source: Wrocław University via Gesher Galicia.

In Rohatyn the Kasten family lived in a single room with three other families, including the Drach couple Zale and Manja from Bukachivtsi with their two small sons and Zale’s father. Later they learned that Yossel’s older brother Dudshe was also in the ghetto with his two daughters; his wife and Yossel’s sister Rivke had been shot in a field with Rivke’s two children. During the winter of 1941, Yossel and Lina’s infant son was shot to death in front of them during a “children’s aktion” in the Rohatyn ghetto.

Over many nights, Yossel and his brother dug a large pit in the ground adjacent to a latrine and covered it with wooden planks; although the smell was terrible, the pit served as an effective bunker during aktions for both Kasten families. They stayed together there for two nights during the March 20, 1942 aktion, when most of the Jews in the Rohatyn ghetto were rounded up and shot at prepared pits south of the town center. With rumors of another children’s aktion circulating among the Jews, despite Lina’s fears Yossel Kasten resolved that the family should escape the ghetto and take shelter in a forest near Bukachivtsi, where he had heard other Jews were surviving; others they knew, including Dudshe, had heard rumors of Jews dying in the woods and decided to stay.

Yossel prepared and memorized their path through the ghetto and its barbed-wire boundary, but beyond that the route and the villages were unknown to him. They crept out into a dark midnight, and carrying their very young children tied onto their backs with torn sheets, Yossel and Lina made their way to the ghetto fence, where dogs heard them and their barking alerted the guards; Lina was shot in the leg as she passed through the fence, but was able to keep moving. They paused in the old Jewish cemetery on a hill above the town center, then passed through the Christian cemetery below, where they heard others in hiding. From here they continued on roads and paths during the night, hungry, thirsty, and confused about the best direction to take. During daylight they tried to sleep and avoid discovery. Expecting to need several nights to travel the roughly 30km to the forest, in fact the journey took close to two weeks, much of the time spent lost, hiding, running to evade capture, and foraging for food. In addition to frequent threats, a few people aided the Kastens, some grudgingly and some willingly; once, a child gave them her bread to eat. One man who encountered them was initially aggressive, but eventually agreed to help them in exchange for some tailoring work by Yossel.

A map from 1930 showing the Kastens’ escape goal: a forest surrounding the village of Vytan (Witan) northeast of Bukachivtsi. Source: WIG Archive, composite by RJH.

This man directed the family to a road Yossel recognized, near to Bukachivtsi and one more night’s walk to their forest destination. They crept to the farm of a Polish woman Yossel had befriended before the war, a poor widow with two young daughters. The woman, named Szostakowa, gave Yossel food and a knife to remove the bullet from Lina’s leg, but urged the Kastens to move away quickly because of the threat to her and her daughters; there had been frequent police and German raids, so the family trudged off in the dark and then lay down in dense bushes and mud for shelter for another long day.

The next night the Kastens finally reached their destination: the forest which surrounded the tiny village of Vytan, only five kilometers from Bukachivtsi but nearly isolated from the settlements in the area. Rumors that other Jews were surviving there were encouraging, but it wasn’t clear how they got by, and immediately Yossel realized they needed shelter against the elements and access to food. At least there were none of the immediate threats of the ghetto, and from their prewar life the Kastens already knew they could forage for mushrooms and berries in the forest. For more substantial and varied provisions, they would have to leave the forest at night to steal beets, cabbages, potatoes, and anything else they could find from fields and barns of nearby farms.

The forest was very dense, which helped to hide the family, but there were frequent raids by Ukrainian militias and occasionally by Germans. The Kastens believed there were other Jewish individuals and families in the forest, and possibly Polish and Jewish partisans as well, but they did not encounter any for a long time. Leaving the deep forest to look for food took all night, with the risk that Yossel would be captured or become lost in the dark on his return. Very rarely he would venture further from the forest to beg for food or other items from the widow Szostakowa, again endangering both himself and the poor woman’s family. Once both Lina and Yossel left their children alone in the forest to try together to bring back animal feed for the family; while gathering food in a barn they were discovered by the farmer, but recognizing their plight he loaded potatoes into a sack for them, and gave Lina another sack to serve as a dress. The man in the nearby village who had earlier helped them find the road to Bukachivtsi continued to give them bread in exchange for mending his old clothes, when Yossel was willing to risk the long journey to work for him.

Eventually Yossel encountered partisans in the forest, who advised him to take his family deeper into the forest to a swampy area rarely visited by local villagers; they told him other Jews were also there. The Kastens met some others, including a few they knew from before the war, but none were willing to risk sheltering together with the Kastens’ young children. Most of the time when Yossel and Lina saw shadowy figures in the forest, they kept quiet out of fear, even when they guessed the others were Jews. Unable to dig a shelter by themselves with their bare hands, they stole a few tools from barns around the forest, but were too weak to make any progress. In a shallow depression and covered by the branches of a large bush, the family endured their first months in the forest.

Then one early morning on his way back through the forest after scavenging for food, Yossel saw a couple with two small children; when he called to them softly “amchu” (your people) to indicate he was Jewish, they returned the call. A joyful meeting followed, as the other couple were Yossel’s childhood friend Josef Blitz, his wife Berta (née Faust) from Rohatyn, and their children Cipora and Abraham, one and five years old. A few days later, they encountered another family: the Drachs with whom they had shared a room in the Rohatyn ghetto, now six in total including two young boys.

The three families resolved to work together to create a shelter which could hide them and give better protection against the next winter. Sender Drach, Zale’s father, had worked as a carpenter and led the excavation and construction work. The men dug deep for weeks; the women carried the soil away and spread it to disguise its origin. They cut small trees to reinforce the pit walls, and covered the opening with branches and soil to mask it; over time grasses and other plants grew on top, camouflaging the bunker. Openings for entry and for air were covered with cut shrubs, which they replaced from time to time as they dried. On the floor of the pit they laid sacks and straw taken from village barns. Sender cut steps into a tree trunk to serve as a ladder.

Tonia Kasten in a portrait from 1948.

Source: Dina Dor-Kasten via JewishGen.

With fourteen people in the bunker, the space was very cramped, but safer than living openly on the forest floor. For over two years the three families shared this space, leaving it only when apparently safe to do so, and for food or other needs. Privacy was non-existent; the families lived as one, sharing child-caring and group tasks so others could forage or work with the partisans. Sanitation was difficult; buckets were used when necessary, sometimes with no opportunity to empty them for days. In the close quarters, lice proliferated; Lina cut off her hair for the first time in her life to minimize that breeding ground. When any in the bunker fell sick with sanitation-related illnesses, inevitably the others did also. Meanwhile, nearby villagers evolved their defenses against food thefts, and followed some Jews into the forest to discover their bunkers, which they reported to the Germans for rewards. Once, a Polish forester warned the Jews that a forest siege was planned; the Kastens and their friends were prepared for that, but still had to remain in their bunker for four full days without food or water. Many Jews were killed in the forest during the siege.

Despite all of these difficulties, some traces of life stubbornly persisted. Lina Kasten, a naturally timid woman, found courage within herself to venture out to locate Yossel and bring him to the bunker when he was lost in the forest in snowy winter, and when he was ill she went in Yossel’s place with another man to plead for food from an elderly couple in Vytan – which they gave generously. Lina and Yossel even brought new life into their troubled world, a son who lived only an hour in the bunker, and then a daughter Tonia in 1944 while Germany still occupied the region; Tonia’s birth served as a kind of good luck sign for the Kastens, and she survived the war with her family. The women tried to maintain a semblance of traditions, pretending to light shabbat candles on Fridays and reciting the prayers. Despite exhaustion and sickness, Josef Blitz made a kind of school for the young children, teaching them the Hebrew letters, numbers, and simple arithmetic. And more: when a troublesome villager repeatedly entered the forest to harass the Jews in hiding, beating them and trying to capture them for reward from the Germans, Yossel and some of the partisans went to his house at night and killed him.

The white dress given by Szostakowa to Yossel for Dina.

Source: Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection.

In the bunker in early 1944 the families endured another winter, wearing down with malnutrition, illnesses, and exhaustion. A lucky chance to steal a horse for food brought much-needed protein to their diets for a while, but also problems as their bodies struggled to digest the unfamiliar nourishment. The Kastens continued to rely from time to time on the widow Szostakowa in Bukachivtsi; the Blitzes likewise were aided by a woman named Chana Warwanka who had worked for Josef Blitz’s parents in town before the war. Finally summer came, bringing a lot of movement of German troops even at the edge of the Vytan forest. Then one early morning in August, Lina pushed aside the bush covering the bunker opening and stood on the ladder to peer around; her eyes fell on a man’s boots nearby, belonging to a Soviet soldier: for the Kastens and their companions, the war was over.

For another two months, the families remained in the forest, in terrible physical condition and without means to improve their health and appearance. Yossel visited Szostakowa at her home, bringing back worn clothes including an old white dress from her daughters for Dina. He also visited the village man who had helped them in exchange for tailoring, bringing back items including a shirt for Shmulik. Then they attended to their hygiene, washing their bodies with water and a rag for the first time in three years. Gradually the children began to explore the forest as place for play rather than danger.

Lina estimated that about 30 Jews survived the war in the Vytan forest (other sources suggest only 20), of perhaps 200 who had hidden there; their bunker thus made up a third or more of the forest survivors. The Blitzes and the Kastens decided to return to Bukachivtsi in October, but found the town unwelcoming; the Ukrainian neighbor who had taken the Kasten house would not let them back in, but allowed them to sleep in a shed behind the house. The town’s synagogue had been stripped and burned, and the gravestones in the Jewish cemetery had been shattered. Finding few opportunities for work or life in Soviet Bukachivtsi, when the ethnic “resettlement” campaign organized by Polish authorities and the NKVD accelerated in autumn of 1945, the Kastens decided to join other Jews and Poles who boarded trains and traveled to the refugee facility at the former German concentration subcamp in Reichenbach, later called Dzierżoniów. Another daughter, Klara-Chaja, was born there.

Dina Kasten with Cipora Blitz in Poland, 1946. Source: Dina Dor-Kasten via JewishGen.

Yossel now pressed his hope to emigrate to Eretz Yisrael, still administered as British Mandatory Palestine, and made contact with members of the Bricha underground movement to prepare a path. This required that they move clandestinely to another country, as refugees in central and eastern Europe were forbidden by the British to settle in Palestine. Bricha leaders allowed them to join a secret transit group only when Klara-Chaja was a year old, so in late summer 1946 they moved on foot at night across the Polish-Czechoslovak border and from there to Linz, Austria where they settled at the Wegscheid refugee transit camp to wait their chance to make aliyah. Among other Jews with similar wartime experiences, the Kastens began to create their new life. Lina met by chance a cousin from her Fuchs family at the camp, the only other known survivor of their extended clan. Another child was born to the Kastens in 1947, a boy, named David (Dudshe) after Yossel’s brother who died in Rohatyn. Then in September 1948, the Kasten family at last left by train and then ship to become citizens of the new state of Israel.

Lina-Liba and Josef Kasten in Tel Aviv in 1949. Source: Dina Dor-Kasten via JewishGen.

In the final short section of the memoir, the first-person voice of the narrator shifts from Lina-Liba Kasten to that of her daughter Dina, to present her memories as a girl of eight years in the Wegscheid DP camp through the train trip to Italy and then the ship passage to Israel. Once landed, the family stayed for six weeks in a transition camp in Ra’anana, then found housing in Jaffa. Working with an integration office, the family learned Hebrew, Lina and Yossel found jobs, and the children entered schools. A few years later, another daughter was born, Rivka, named for Yossel’s murdered sister. Dina notes that at each station of their journey, the Kastens brought forth a child: Shmulik and Dina in Bukaczowce, Tonia in the bunker in the Vytan forest, Klara-Chaja in Dzierżoniów, Dudshe in the Wegscheid camp, and Rivka in the young state of Israel – a sabra.

The Central Database of Shoah Victims’ Names at Yad Vashem contains pages of testimony for many murdered members of the Kasten family of Bukachivtsi and the Fuchs family of Perehinske, including the siblings of Josef Kasten, the mother of Lina-Liba (Fuchs) Kasten, and a daughter of Josef and Lina-Liba; these testimonies were left by Dina-Dor Kasten and other survivors. Elsewhere in the Yad Vashem documents archive, survivor lists and records name several members of the Kasten family in the memoir; the database entries for Dina and for her elder brother Shmuel both name them as “Victims Recorded in Righteous among the Nations Files” with a file in record group M.31, sub-group M.31.2, file number 13612. That file is not online in the Yad Vashem Righteous Among the Nations Database, apparently because the research has not been successful.

Elements of the Memoir with Value to Rohatyn Studies

During the Holocaust, the forest was one of the few options Jews had to try to escape the murderous pursuit of the Nazi Germans and their collaborators. Even though it was fraught with danger – exposure to the elements, hunger and disease, and a local population who were often not any kinder than the fate they faced from Nazi soldiers – taking their chances in the forest was thought by some to be better than being incarcerated in ghettos, concentration or forced labor camps. Jewish men, women and children sought ways to survive both as individuals and as family units among the leaves and trees. Survival in these inhospitable locations was difficult, even for the fittest of adults. For young children it was nearly impossible, and their presence often risked the safety of the entire group.

– from “Survival of the Smallest Children in the Forest During the Holocaust”; Simmy Allen for Yad Vashem; Memoria Magazine (publication of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum); vol. 20 (May 2019), p.16~19

An aerial view in 2023 of the forest surrounding the village of Vytan; Bukachivtsi is at lower left in this view. Bing Maps image © Microsoft and Maxar.

Although there were many stressful events for the Kasten family throughout their Holocaust experience, two scenes in Dina Dor-Kasten’s documentary tale of her parents’ survival with very young children in the ghettos of Bukachivtsi and Rohatyn, during their escape, and in the forest, are particularly pitiful. At one point during the journey on foot at night from Rohatyn, exhausted and starving, despondent at not being able to feed or even give water to Shmulik and Dina for several days, Lina and Yossel considered leaving their children in a barn where they hid in the hope that the farmer might be compassionate and give them a chance to survive; the couple did in fact leave the barn when the children were asleep, but then turned back, deciding that if they must perish they would do so together. Later in the forest, Yossel met a dejected Jewish couple who had abandoned their children with bread and water, unable to bear their suffering and wishing a better fate for them; the Kastens heard later that the couple had been captured and killed in a raid on a cemetery hiding place outside the forest. These scenes remind of others in the Rohatyn-area memoir collection in which parents were forced to silence young children in hiding to avoid detection, resulting in suffocation.

There are other memoirs of the region which feature extended periods in forest shelters, including Jack Glotzer’s survival with some of his cousins and his overlapping story with Tzvi and Bertha Wohl of Burshtyn, as told by their daughter Marta in a speech included in an addendum to the Rohatyn Yizkor Book. The story related by Lina Kasten to her daughter Dina is no less terrible and much more vivid, giving details not only of the practical challenges of survival but also the gradual physical and emotional degradation which forest life forced on the family. This story is especially valuable as a rare record which also represents the lives of a few hundred anonymous Jews who entered the Vytan forest hoping for safety, but were unable to last through the war to tell their own story.

Most memoirs and testimonies of Jewish life during the Holocaust include some information which conflicts with other recorded histories and the recollections of other survivors, especially those which were written or spoken several decades after the events. As noted above, the Kastens were forcibly expelled from Bukachivtsi to the Rohatyn ghetto in 1941, a year before the Pinkas ha-kehillot Polin records the event, but the Blitz family also testified to the expulsion in 1941. About their escape from the Rohatyn ghetto to the Vytan forest, the Drach family confirmed that they joined the Kastens in the forest in 1942, but Josef Blitz testified that his family did not leave Rohatyn until just before the ghetto liquidation in June 1943. These differences cannot be resolved today.

Hidden Under the Earth also relates a unique event not recorded in other memoirs of the Rohatyn ghetto (to our knowledge), of the “children’s aktion” in which Lina and Yossel as well as other parents were forced to choose one of their children for sacrifice and then watch while the murder was committed. This scene, reminiscent of William Styron’s novel Sophie’s Choice, is shocking, so much so that Dor-Kasten says she never even heard from her parents that they had had a third child in Bukachivtsi; the information came to Dor-Kasten from a surviving cousin of Lina’s in whom she had confided, after both Yossel and Lina had passed away.

Finally, the memoir is important for describing, and in one case partially naming, individual Polish and Ukrainian people who aided the Kastens at various points of their escape from the Rohatyn ghetto and during their years hiding in the forest. Not all of these people provided food, clothing, tools, or other support readily or kindly, but all of them did so at great risk to themselves and their families, given the German law against aiding Jews – a prohibition which carried the death penalty. These people also stand out in contrast to others who, as described in the memoir, actively attempted to reveal, harm, or kill the Kasten family and others during the German occupation. After the siege in the forest, during which the families in the bunker had no food for four days, Yossel Kasten and Zale Drach went together to visit the widow Szostakowa near Bukachivtsi; Lina said that she gave the men bread, cooked potatoes with fat, beets, and two bottles of milk: “The two men stood at the door, amazed, thanked her warmly, and hugged the generous woman who gave them all this – more than was actually possible for her and at the risk of her family… As long as we stayed in the forest, the Polish peasant woman risked her life and that of her daughters by feeding us when Papa turned to her.”

Additional References

Much of the information presented here is summarized directly from the memoir in an informal English translation made by Rohatyn Jewish Heritage. Other references include:

- Yad Vashem archive record “Documentation regarding the experiences of the Kasten family, 1941-1948“, submitted by Dina Dor-Kasten; Item ID 10857224, Record Group O.6 – Poland Collection, File Number 1470

- Yad Vashem Central Database of Shoah Victims’ Names, including search results for Kasten in Bukaczowce and for Fuchs in Perehinsko

- Yad Vashem Shoah Names Database, including search results for Kasten in Bukaczowce

- Yad Vashem file from the Collection of the Righteous Among the Nations Department, record M.31.2/13612 (RJH correspondence)

- Yad Vashem project Gathering the Artifacts

- Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection, Dress worn by Dina Kasten while in hiding in a forest in Ukraine

- “Survival of the Smallest Children in the Forest During the Holocaust”; Simmy Allen for Yad Vashem; Memoria Magazine (publication of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum); vol. 20 (May 2019), p.16~19

- Donia Gold Shwarzstein’s Remembering Rohatyn and Its Environs, including three short histories of Bukachivtsi during wartime by survivors Chedveh Weisman, Leon Gewanter, and Leon Schreier (pgs. 360~367)

- the same original material in the Yizkor Book for Rohatyn: The Community of Rohatyn and Environs, which is available online in an English translation as part of the JewishGen Yizkor Book Project

- USC Shoah Foundation Interviews with Rohatyn Survivors and Others, an article on this website

- the JewishGen Kehilalinks pages on Bukaczowce, including especially the Kasten Family page and the Blitz Family page

- the Bezalel Narkiss Index of Jewish Art of the Center for Jewish Art at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, their photographic documentation of surviving Jewish heritage objects in Bukachivtsi, including two synagogue buildings, the historic cemetery, and gathered Jewish headstone fragments

- the chapter “Bukaczowce” in the Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities in Poland (Pinkas ha-kehillot Polin) Volume II, p.89~91, in English translation provided by JewishGen

- the Yahad – In Unum Map of the Holocaust by Bullets, especially the page of data and testimonies for Bukachivtsi

- The Shoah in Rohatyn, a historical timeline on this website

- Rohatyn’s Wartime Righteous Gentiles, an article on this website

For their input and advice with additional information, contacts, and more about this memoir and related history, Rohatyn Jewish Heritage thanks our long-time colleagues and friends Dr. Alexander Feller, founder of the Rohatyn District Research Group; Edgar Hauster, researcher and blogger on Rohatyn, Chernivtsi, Moldova, Romania, and more; and Cipora Blitz, a Holocaust survivor and member of the Blitz family who hid with the Kastens in the Vytan forest. We especially thank the author of this memoir, Dina Dor-Kasten, and her husband and the book’s editor, Lior Dor, for their careful review of this article and for their helpful input, comments, and corrections.

This page is part of a series on memoirs of Jewish life in Rohatyn, a component of our history of the Jewish community of Rohatyn.