![]() Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Introduction

On the occasion of the 75th anniversary of the killing of thousands of Rohatyn’s Jewish citizens during the Holocaust under German occupation, following a memorial prayer by the Rabbi of Ivano-Frankivsk and a short commemorative speech by Marla on behalf of Rohatyn Jewish descendants, retired local school teacher Mykhailo Vorobets recalled for the assembled group his own experience as a child at the mass grave site where the group was then standing. We described Mr. Vorobets’ talk briefly in the news article we posted from that day, but on this page we present his words in full, along with additional information and interpretation. Mr. Vorobets has spoken about this topic to us and to others on several occasions; we are fortunate that we have a recording from this event which we can share. This testimony closely relates to a series of interviews with local Ukrainian witnesses to the Holocaust in Rohatyn conducted by Yahad – In Unum the previous year (and which Mr. Vorobets helped to arrange).

Jennifer Dickinson accompanied us that day and made the recording for this page, as well as an artistic interpretation of Mr. Vorobets’ act of remembrance; we include all of this below. Our long-time friends and supporters Ihor Klishch and Iryna Matsevko provided interpretation to English on that day at the site, and helped to interpret questions and answers as Mr. Vorobets spoke. Our dear friend Nataliya Kurishko, who has translated many of the pages on this website into Ukrainian, provided the video transcript from which the English translation below was made. We are grateful to each of these friends, and to all who joined us on that sad day.

The events Mr. Vorobets described took place on 20 March 1942 and through the days which followed, when he was a boy of seven years old. The place where the events and Mr. Vorobets’ experience took place, and where we stood in commemoration of the lost lives (and way of life) exactly 75 years later, is now known as Rohatyn’s south mass grave, near an unpaved road connecting the Babintsi neighborhood of Rohatyn with the village of Putiatyntsi to the southeast. Two memorial markers stand adjacent to the road near the site, but the locations of the mass graves themselves are unmarked. Events at this site formed part of the larger history of Rohatyn’s Jewish community during the Shoah.

Mr. Vorobets’ Remembrance

Mykhailo Vorobets was born in a village called Verbylivtsi (pre-war: Wierzbiłowce), only 2km south of the Rohatyn town center. His father worked in the area, so the family was frequently in Rohatyn, and Mykhailo has spent his adult life working and living in Rohatyn, as a teacher and historian and in several other capacities. He is well known in Rohatyn, in part because he was a teacher to nearly everyone who lives in town, but also because of his decades-long dedication to preserving and communicating the history and heritage of the town and its multicultural past; he also serves as an informal ambassador on behalf of Rohatyn to visitors from around the world.

We first met Mr. Vorobets in April 2011 on our second visit to Rohatyn after taking an apartment in Lviv, and in that meeting we learned from Ihor that Mr. Vorobets had been caring for the Jewish heritage of Rohatyn and serving as a contact for Jewish survivors and descendants in Israel for years, but his connection had been lost because of the passing of those survivors. Mr. Vorobets introduced us to the persistent presence of Jewish headstone fragments buried under streets and yards around town, dating from the time of the German occupation, and our heritage project began with this initial exchange, building on what Mr. Vorobets, Jewish survivors of the Rohatyn ghetto, and others had done in the past.

Mr. Vorobets’ words at the south mass grave on the 75th anniversary of the killing are compelling. An English-language version of his full address, transcribed from the video recorded by Jennifer Dickinson, is provided at the bottom of this page.

An Artistic Interpretation of the Long Reach of Memory

Dr. Jennifer Dickinson is Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Vermont (UVM) and faculty Director of UVM’s Center for Teaching and Learning. She is a specialist in cultural and linguistic anthropology; her research focus has integrated storytelling, the use of language and graphic design in material culture, and the anthropology of work. Among other interests, she studies how personal narratives intersect with social change in the lives of individuals and communities.

At the time of the memorial event in Rohatyn in 2017, Jennifer was teaching and researching in western Ukraine on a Fulbright Scholar grant. This recent work, with sponsorship through Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv, combines ethnographic and oral history studies to explore continuity and change in personal identities in the Deaf community of Ukraine. Her recent work continues more than two decades of research and extended residence in western Ukraine, through which she has also acquired facility in Ukrainian spoken language and dialects, and in Ukrainian Sign Language.

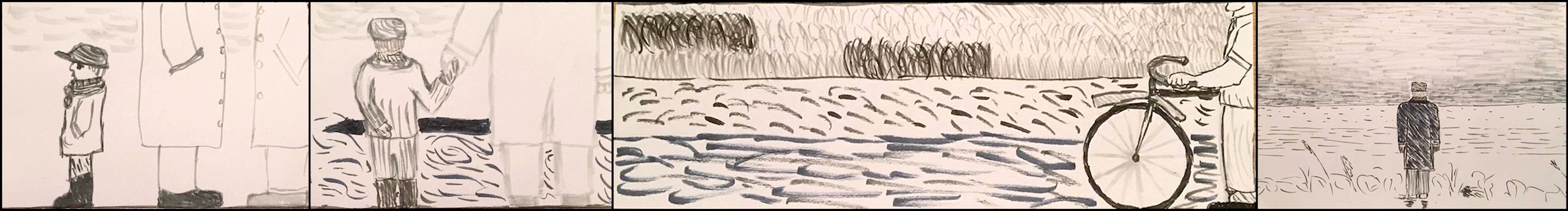

Jennifer is thus proficient and knowledgeable in the transformation of experience into personal history and identity through a variety of communication means and media. She also experiments with the distillation of her own and others’ experiences through the medium of comics of her own design, often silent (without text). After participating in the Rohatyn memorial event, she drew a four-panel comic strip of her impressions of Mr. Vorobets’ speech at the mass grave site, shown here below.

Although frequently associated with humor and light topics, the medium of comics expanded and adapted in the 20th century into a variety of genres for entertainment, social commentary, and complex story-telling, including in graphic novels adapted from earlier conventional fiction or from original plots; Will Eisner was a well-known cartoonist who worked in many themes and styles. Although the medium of comics once seemed antagonistic to themes of the Holocaust, Art Spiegelman’s Maus helped to soften that apprehension in the public’s eye, and comics are now recognized among the many different art forms which have the ability to articulate and testify to experiences which are difficult to express in words, or only in words. In 2017, coincident with the commemorative event in Rohatyn, France’s Holocaust museum in Paris (the Mémorial de la Shoah), presented a multimedia exhibition on The Holocaust and Comics, illustrating the history and development of comics as an art form capable of reaching beyond common boundaries of experience.

In the strip below, Jennifer interpreted Mr. Vorobets’ story about his experience as a young boy standing on the edge of horror, and the lasting impact that day 75 years before has had on him. Jennifer’s summary of the scene follows the graphic.

Mykhailo Vorobets at the Rohatyn south mass grave site, in 1942 and 2017. Graphic © 2017 Jennifer Dickinson. Click on the image to enlarge it.

1. On March 20th, Jews were marched out of Rohatyn and taken to two locations, where they were killed and thrown into large pits. Mykhailo recalls that his father, who had many ties with the Jewish community, was told by an acquaintance about the killings. His father, at first scared and reluctant to go when he had his seven-year-old son with him, decided in the end to see what had happened.

2. The two walked out of town and up the road to an open field, where two giant pits had been dug a ways off the road, one closer, and the other farther away, at a diagonal from the first. Mykhailo, holding his father’s hand, wanted to look away from the horror of the thousands of slaughtered Jews, already lying in the open graves for several days.

3. Later, grain was planted in the fields, and there were two spaces, large rectangles, one positioned diagonally behind the other, where the barley grew higher than everywhere else, as if the roots were nourished with some unusual richness in the soil.

4. “This was my one mistake” he says now, “that I never fixed in my mind, or measured where those two rectangles were. If only I had, we would know the location of those graves.” It is this regret that Mykhailo, now in his 80’s, returns to again and again, as if picturing those tall barley stalks in his mind could make the ground speak.

Translation of Mr. Vorobets’ Remembrance

We thank Nataliya Kurishko for the transcript from which this translation was made:

[00:10]: I have said this many times… When I was only seven years old, my father left the village for the city. My father was in very close contact with the Jewish community, because he was a good driver, he had horses and transported things to here from Kalush, and from Lviv. [00:38]: And so, when we went to town that day, we met people from the village of Babyntsi, and from the town of Rohatyn – Ukrainians – and they said to my father: “Come, Vasyl, let’s go to this place where the Jewish people were shot by the Germans.” [00:55]: At first my father did not give his consent, saying: “I am here with my child, the Gestapo could come and beat us.” [01:04]: But the others convinced my father. And my father went with me, he held my hand, and we went to this place together, we left the city. Those pits … [01:19]: … they were not closed yet. It was only now, as an adult, that I realize that a pit of about twelve by twelve and five meters deep had been dug there. There were two such pits. [01:37]: The pits had not been closed yet, only covered by some chemical compounds: lime and chemical compounds were sprinkled. And that was … they were shot on the twentieth, so I guess it could have been two … or on the third day … somewhere around two days after. [01:59]: Of course, I admit one uncertainty about where [the pits were located]. It seems to me that the first grave we approached was here, where this valley is, here is the pit. [02:15]: And then the second grave – by then I was already a little separated from my father, a couple of meters – and it was somewhere around here. [02:29]: That’s about it. I should say, if there were specialists and they knew how to search – and there are such specialists – they would definitely find the pits. When there was a collective farm … [02:41]: I believe that I made a mistake in my life. Why exactly? When the collective farm system was here, … [02:54]: … and they sowed grain crops in this place – barley, wheat, and so on – then in the place where the burial was, the crops rose vigorously. You see, obviously, the root system created such conditions that those crops grew better than others. And it was visible clearly from the road – one square and the second square, but I did not record anything at that time. If I had recorded it, I could specify the dimensions: here, there, I could draw a diagram. I made a mistake by not recording it. [03:38]: So to it find exactly, you must call specialists. And they will definitely tell you. [03:57]: And now that plot … (Here, Rabbi Kolesnyk speaks about his own attempt to define the grave locations, with an instrument in the early 1990s; he agrees with Mr. Vorobets now about the general location.) [04:37]: I may be wrong about the dimensions – five, even ten meters. [04:57]: They were about 40 meters apart. 35 to 40 meters. [05:05]: It’s a pity that I didn’t measure the dimensions during the Soviet times, and that I didn’t record where the plants grew better. [05:25]: One citizen, Ferschleiser, escaped from here. Academician Liubomyr Pyrih, who now lives in Kyiv, wrote about this. It was his neighbor and he, to tell the truth, was also in that column and was waiting for his death. As they were shooting, he jumped first into the pit and rolled over. Because not every person was killed there – some were only pressed against others [in the pit]. He managed then, when the action ended, to rise to the surface. And then he came to his neighbors, to the parents of Liubomyr Antonovych Pyrih, and said: “Look, I miraculously escaped.” And he escaped twice. And what is even more ironic, his mistake is that after Rohatyn’s liberation he went to the [Soviet] Security Service, to serve in the police. And he was killed, because there were various raids. He didn’t have to deal with that at all. He should instead have stood for any kind of physical work, and not go there. [06:49]: Well, who killed him? At that time there were collective farms, there were partisans, then the UPA, those KGB people, the Security Service, the internal troops; they hunted for people, and he agreed to work with them. He may not have done harm to anyone, but why did he go there? And Liubomyr Pyrih wrote in his memoirs, under the heading “Once Upon a Time”: “He did not have to go there. We would have respected him, his experience alone would have served our history a lot.” [07:29]: It was really a big tragedy. How many worlds there are, obviously, in such a small town, where there were at most seven thousand people, half of them Jews, and in one day they all were destroyed. This is a tragedy! This tragedy was terrible. When I saw all this, I said, “Dad, let’s run away because I’m scared.” There the mass of the people lies. Blood flows, the river flows. I must say it’s unpleasant for a child to watch. So I will never forget it, no matter how long I live. [08:17]: I have collected four such episodes, events where our local people saved. And I will tell this to the students at school. Even today there will be a lecture, and I will tell them how everything happened here. [08:37]: One woman, Maria Vasylivna Tsaper, still lives here; she escaped. Her mother actually saved her. Her father was shot, then her mother gathered up this child at night and said: “Go, daughter, along the river Hnyla Lypa. Go to where people are. Because sooner or later we will be killed.” And the child gained courage – a seven-year-old child – and she went to find people. And so she wandered from one village to another; everyone was afraid to take the child in. They fed her, washed her, and then sent her toward the Lviv oblast. So the child wandered, wandered around the region. And then she went back to the village of Lypivka, sat down near the church; there was a holy service taking place in the church. She, poor thing, began to cry. The church sexton approached her and asked: “Why are you crying, child? To whom do you belong?” And she said: “I am of the Jewish nation, my mother was destroyed, the shootings took place here on the ground in Rohatyn, and I want to live.” Imagine – a seven-year-old child. And he actually saved her. [10:18]: She still lives. I interviewed her. She lives in Rohatyn. And plainly she told me all about it, how she escaped, how the priest was called to baptize her – so that she would not be killed. He gave her a certificate which said that she was a Christian, so that she could live. She married, but her husband has died. Her child is disabled. But she told me all this very conscientiously, with a feeling of love for her Ukrainian rescuers. [11:06]: I was a member of the executive committee of the city council. There was a request to return her house, 109 Halytska Street, to her ownership. This question was heard, and the house was returned to her. Her daughter got married here, they live well, they repaired some rooms, they completed things. In short, she remembers her rescuers. [11:43]: There was also a second case. It is about Sebastian Nekhai – he saved a doctor and his wife. This story is also quite interesting.(Then the interpreter asks if Mr. Vorobets will be telling the story during the lecture; the answer is yes, and this story is long and complicated.)

This page is part of a series on memoirs of Jewish life in Rohatyn, a component of our history of the Jewish community of Rohatyn.