![]() Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Roman Korytko; “У горнилі боїв” (“In the Crucible of Battle”); from the book Діти війни – Життя і долі (Children of War – Lives and Destinies); compiled and coordinated by Vasyl Petriv for the Lviv Regional Public Organization “Protection of Children of War”; Spolom; Lviv, 2013.

Introduction

I remember the day when my father was traveling to Rohatyn in a cart and took me with him. Before entering the city, near a clay field above which a high yellow wall protruded, we were stopped by the Gestapo, and we saw their guards herding a large group of Jews of all ages: old, young, and small children. There were also mothers carrying their babies. As soon as the Jews were brought to the Clay Mountain, the road was opened for us. We had traveled perhaps two or three hundred meters when a machine gun started firing…

This page describes a brief (8-page) memoir by Roman Korytko, a Ukrainian literary writer born in 1935, covering his recollections of his life in Cherche near Rohatyn from the start of the German invasion of Soviet-occupied eastern Poland in 1941 under Operation Barbarossa until the Red Army drove the German military westward out of the region in 1944, ending the active phase of World War II in what is now western Ukraine. Korytko’s memoir, called “У горнилі боїв” (“In the Crucible of Battle”) is one of 88 individual personal histories of wartime by Ukrainian men and women legally classified as “children of war”, having been born between 1927 and 1945. The book is a product of a Lviv regional public charity organization formed of and by children of war to promote the unique issues of people whose early lives were affected by the war and to work for protection of their social benefits.

Korytko is a novelist and short-story writer, member of the National Union of Writers of Ukraine, and winner of literary prizes named for the Lepkyi brothers (in 2000) and for Iryna Wilde (in 2008). His novel Брати Рогатинці from 1999 is a historical fiction about the brothers Yuri and Ivan Rohatynets, born in Rohatyn in the 16th century. Since 1997 he has produced a series of historical essays on villages of the Rohatyn Opillya region, including Cherche, Stratyn, Dobryniv, Danylche, Chesnyky, Putiatyntsi, Pukiv, Klishchivna, Lipivka, Kryvnia, and Voroniv, as well as a separate essay about the sanitorium at Cherche. Korytko was trained at the Stanislav Pedagogical Institute, now the Vasyl Stefanyk Precarpathian National University in Ivano-Frankivsk, and later moved to Lviv.

The book which features this memoir is no longer in print, but good-quality new old stock and used copies are available from independent booksellers and online auction sites in Ukraine.

A Brief Summary of the Memoir

Roman Korytko calls his memoir “In the Crucible of Battle” because Cherche where he was born in 1935 saw strong military action twice as the German-Soviet battle front passed eastward on the main road through the village in 1941 and then again in the opposite direction in 1944. Korytko grew up in a poor family with only Ukrainian neighbors; an estimate of the village population at the start of World War II was 1765 ethnic Ukrainians and 5 Jews, with no resident ethnic Poles. Cherche was at least 500 years old when Korytko was born, and since the 1930s has been home to a popular spa and sanitorium which included a pavilion and kosher kitchen specifically built to serve wealthy visiting Jews seeking health treatments at the local mineral springs which had been discovered early in the 20th century.

Korytko begins his story at age 6, with a parade of Soviet tanks and trucks with Red Army soldiers passing through Cherche one day in 1941, some of them returning the next day on horseback to feed their horses and themselves. When a German fighter plane roared overhead, the Soviets scattered on foot, leaving their horses (which had been taken from Cherche a few days earlier) and disappearing. Not long after, German soldiers appeared in cars and on motorcycles, smiling and asking the elder villagers (who spoke some German from the time of the Austrian imperial presence in Galicia before World War I) about the retreat of the Soviets, and about their weapons. After the Germans continued on to Rohatyn, Korytko watched as a Soviet soldier who had been hiding with a village girl apparently decided he was doomed, so he threw his rifle away and blew off his own head with a grenade. Village men collected the soldier’s corpse and buried him in the local cemetery.

At the beginning of the German occupation, lacking administrative resources, Korytko says that the military was unable to control the villages and towns smaller than Rohatyn, leaving room for the OUN to elevate Ukrainian national spirit with community theater, choral groups, and poetry; in Cherche, Korytko and a friend were invited to recite Taras Shevchenko’s poems “A Dream” and “I Was Thirteen (N. N.)”. This revival was crushed when Germany created Distrikt Galizien as an administrative unit of the German zone of occupation and installed their headman in the Rohatyn district, Hans-Adolf Asbach. Later in 1941, as the Jewish ghetto in Rohatyn was being formally established, young Ukrainians were taken for local forced labor and others were deported for forced labor in Germany, as was done in many villages in the district.

Although merely six years old when the Rohatyn Jewish ghetto was established, and eight when it was liquidated, Korytko was aware from others what was happening there on the orders of the Germans. One day his father took the boy with him by cart to Rohatyn; en route to the city by the main road they were stopped by Gestapo and forced to wait while Jews were herded off the road to what soon became the site of their murder and burial, the north mass grave of the ghetto liquidation in June 1943. Witnesses’ descriptions of the killings spread through Cherche, marking even the very young with lasting impressions. It was also known directly and through rumors that a small number of Jews survived in the forests after the liquidation; Korytko relates that one evening two bearded Jewish itinerant tinkers or petty merchants who were known in the area from their dealings with the villagers appeared at the door of his family’s home in Cherche while his grandmother was cooking, to beg for food.

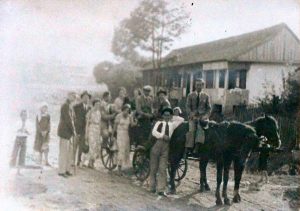

A jazz band in Cherche for performances at the sanatorium in 1931.

From an exhibition at the Lviv Ethnographic Museum.

Korytko then describes the ongoing struggle between armed UPA partisans and the German occupation forces, including a mass arrest and execution in 1943 of 250 Ukrainian nationalists near the UGC church on the Rohatyn central square. In a longer passage, he relates how Cherche was under threat of complete destruction due to the kidnapping by UPA fighters of two German doctors from the regional headquarters at the sanatorium in the village. A tense day passed, as nobody in the village knew what had happened to the doctors, but in the end they were released without harm in Rohatyn after performing surgery on an insurgent commander who was seriously wounded in a battle with the German army two nights earlier. Korytko quotes from the 1955 memoirs of one of the captive doctors to confirm that he was treated humanely and respectfully while he did his work.

As the Soviet military regained ground in the region, Cherche suffered artillery fire and there were air battles between German and Soviet fighters. On the ground, the Ukrainian insurgent army now had two enemies to contend with. When the front line reached Rohatyn, villagers fled into the forests to escape gunfire and exploding shells; Korytko and his family became trapped in the forest without sufficient food while the Germans fled west through Cherche with the Soviets close behind. Running into the village in search of food, Korytko narrowly escaped injury when a bomb exploded near him, damaging a villa in front of the sanatorium where he had been sheltering. After lying still in a trench for most of the day, Korytko searched for his family and waited for the front to pass them by in a neighbor’s cellar.

Elements of the Memoir with Value to Rohatyn Studies

This memoir confirms again that even young children, even in villages, recognized that something terrible was happening during the Holocaust, both as direct eyewitnesses and from hearing the adults around them discussing the situation. Roman Korytko was eight years old when he saw the column of Jews being assembled for the killings and then heard the shooting at what became the north mass grave in Rohatyn; about his recollection of the horrors of war, he writes that they are “still imprinted in my childhood memory, as if on a screen… [a]nd they were captured not in a generalized, selective way, but with details, as if everything happened yesterday, from which it is impossible to recover.” Growing up in the village of Verbylivtsi, Mykhailo Vorobets was seven years old when his father took him to Rohatyn on business, and the pair was talked into going to the south mass grave there a few days after the killing of three thousand Jews on March 20, 1942; 75 years later Vorobets said during a commemoration at the site, “I will never forget it, no matter how long I live.” Of the nine Ukrainian witnesses to the Holocaust interviewed by the French NGO Yahad – In Unum in 2016, seven were classified “children of war”, aged eight to fourteen and most living in villages around Rohatyn when the first mass killing was perpetrated there; their recollections of the sights and experiences brought back feelings ranging from extreme sadness to bewilderment to fury, and several cried during their testimonies, many decades after the events.

The experience of Yahad – In Unum witness YIU/2100U compares closely to that of Roman Korytko. He was born in 1930 in the village of Koniushky about 10km south of Rohatyn; his family was subject to oppression by Germans and especially by Soviets during and after the war. The witness was about thirteen years old when he joined his father to collect wood in a forest near Zalaniv, close to Cherche. On their return home by cart, they saw a crowd of perhaps a thousand Jews near the clay pits and brickworks north of Rohatyn, and saw Germans shoot five at a time over the pits, surrounded by a large number of armed soldiers for security. In the video, the witness’s eyes flash with anger at the recollection: “That was so horrible, you can’t even imagine. Just to think… To tell you the truth, I don’t even want to remember that… That’s it, [now] there’s nobody there, oy.”

Additional References

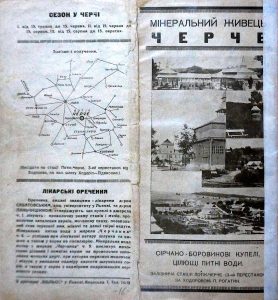

A brochure for the Cherche sanatorium from the 1930s.

From an exhibition at the Lviv Ethnographic Museum.

Much of the information presented here is summarized directly from the memoir in an informal English translation made by Rohatyn Jewish Heritage with the assistance of team member Vasyl Yuzyshyn. Other references include:

- Коритко Роман Федорович (Roman Fedorovych Korytko), the author’s biography from the online Encyclopedia of Modern Ukraine

- Черче (Івано-Франківський район), Ukrainian Wikipedia article on the village of Cherche

- Donia Gold Shwarzstein’s Remembering Rohatyn and Its Environs

- the same original material in the Yizkor Book for Rohatyn: The Community of Rohatyn and Environs, which is available online in an English translation as part of the JewishGen Yizkor Book Project

- Yahad – In Unum Interviews with Rohatyn Holocaust Witnesses, an article on this website

- the Yahad – In Unum Map of the Holocaust by Bullets, especially the page of data and testimonies for Rohatyn

- The Shoah in Rohatyn, a historical timeline on this website

For recommending the memoir as a component of local memory of the fate of Jews of the Rohatyn district, Rohatyn Jewish Heritage thanks our colleague and friend Andre Usach.

This page is part of a series on memoirs of Jewish life in Rohatyn, a component of our history of the Jewish community of Rohatyn.