![]() Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Introduction

For nine days in May~June 2017, archaeologists from the UK conducted a three-part non-invasive ground-penetrating radar survey at sites of World War II mass killing and burial of Jewish victims in Nazi-occupied Rohatyn (now part of western Ukraine). This physical survey was part of a research project spanning two years, which was intended to establish the physical boundaries of the mass graves, to enhance protection and commemoration of the sites. The results of the pre-survey research, site survey work, and post-survey analysis were detailed and explained in a comprehensive report issued by the archaeologists in late 2017; the full report is linked in the References section below.

At two sites in Rohatyn known to have mass burials, the measurements and analysis located and defined probable graves, as summarized below. Difficulties in ground preparation in advance of the survey, and characteristics of the soil itself at the sites, limited the survey results to less than the proposed target areas, and increased uncertainty in some portions of the collected data. Despite these issues, clear survey results were obtained and supported by supplemental research and site observations by the archaeology team for several important locations at the sites. Further work is recommended in future years to extend the well-studied survey areas, and with additional or different equipment to better address the soil conditions in the region.

The research and results summarized here were commissioned by Rohatyn Jewish Heritage (RJH) as part of our ongoing mass grave memorials project, for the benefit of Jewish descendants of families from Rohatyn and the area, for the office of the City of Rohatyn, for Rohatyn’s residents and landowners, and for historians and students of the events of the 20th century in this region. We thank the many people who donated their time and funds to support this effort.

Purpose

The approximate locations of two WWII-era killing and mass grave sites in Rohatyn are known to Rohatyn residents, City officials, and descendants of Jewish families from Rohatyn and the surrounding towns whose relatives were murdered and buried there. Memorial markers are placed at both sites, by the local Soviet administration (in the 1980s) and by Jewish descendants abroad (in 1998). However, in the decades between the Holocaust and the placement of the commemorative markers, under early Soviet suppression of religion and ethnicity, clear memory of the precise locations of the mass graves was lost, even by those still living who had seen the graves with their own eyes as children during the war. It is assumed by all that the locations of the memorials are near the actual graves, but how close is not known with any confidence.

Although the history of the mass graves is dark, they are cemeteries, and deserve the protection and respect accorded other cemeteries. One of the mass grave sites is surrounded by small farm fields worked by locals, the other is within a City-managed building materials station and quarry. In both locations, an area is set aside and untouched based on the position of the memorial markers and informal assumptions about the grave boundaries. In past decades, excavations outside the assumed grave areas have occasionally unearthed human remains.

As outlined in our original Request for Proposal (RFP, linked in the References section below), the primary goal of this survey was to define the physical boundaries of the graves at the mass burial sites with sufficient accuracy to serve as a reliable and permanent public record. This goal also includes identifying adjacent areas which are without graves, and thus need not be preserved and protected against other uses. Respecting Jewish tradition and religious laws (Halakha), direct investigation of the graves through archaeological digging or other disturbance of the ground over the graves was not permitted.

Methodology

The research process conducted by the Centre of Archaeology at Staffordshire University followed a sequence they have used at other sites of conflict:

- review and compilation of historical documentation about the killing and burial events (much of which was provided by RJH), including Jewish and other witness and second-hand accounts, modern and historical aerial photos and maps, and other media;

- interviews and discussions with Rohatyn locals;

- walkover landscape surveys of each of the target sites;

- topographic surveys of the sites using GPS and total station theodolite (TST) tools integrated with electronic distance measurement (EDM, or rangefinder);

- ground penetrating radar (GPR) scanning by passing radar antennas over the ground within the survey areas, measuring signal reflection and attenuation continuously on a tight parallel pattern (typically at 1m intervals) to detect buried human remains and other subsurface features representative of mass graves;

- post-survey three-dimensional radar data assimilation and analysis, coupled with geographical information system (GIS) tools.

Details about the investigation methodology can be found in the full report and in several other references linked below to this summary page.

Prior to the site work by the archaeology team, permission to work at each site was obtained with the assistance of the City of Rohatyn. The sites were prepared by the City of Rohatyn, the Lviv Volunteer Center of the All Ukrainian Jewish Charitable Foundation “Hesed-Arieh”, RJH, local residents of Rohatyn, and a contract work crew: woody vegetation, hard materials, and garbage were cut and removed to a specified height of 5cm above the ground, with mixed success.

During the nine days of GPR measurements and related work, non-technical support was provided to the archaeology team by RJH, a Rohatyn Jewish descendant visiting from Israel, a US Peace Corps volunteer based in Rohatyn, several Rohatyn residents, and several valued friends of our heritage program.

As requested by RJH and following the Centre’s standard practice at sites of Jewish burial, no digging of any kind was made at any of the sites; shovels and other ground-disturbing tools were not permitted within the perimeter of the survey areas. Where new earth was needed to fill holes encountered within the survey areas, that earth was collected from well outside the survey areas, then transported to the survey areas with buckets, and the holes were filled by hand.

South Mass Grave (20 March 1942)

Review of available historical documentation, including Rohatyn Yizkor book testimonies, Rohatyn Jewish survivor memoirs, and the 1944 Luftwaffe aerial photos, plus testimonies newly researched by the Centre at the USHMM, yielded descriptive information about the south mass grave site, its location, and its size, but with considerable imprecision and some conflict between testimony details. Thus the “known” history of the site, about 1.5km southeast of the town square, “behind” the city train station and “near” the site of a former brickworks, containing the remains of some three thousand local Jews, making up the majority of Rohatyn’s Jewish community at the time, killed on 20 March 1942, and buried over the next days in one or two pits, was confirmed as general information but without new precision.

Careful collection of bones and other remains from the ground surface. Photo © 2017 Marla Raucher Osborn.

The archaeological evidence from the non-invasive radar survey, as detailed in the Centre’s full report (Appendix 1), is considerably clearer:

The forensic survey of the southern mass grave site has proved successful in identifying one probable mass grave which is mainly situated between the two current memorials. The grave, although difficult to ascertain the shape in plan from the GPR data, measures at least 33m by 20m and is generally ovoid in shape. The deepest point clearly identified from the data is 3.5m, although it is possible that the pit is deeper than this. The discovery of human remains in this area also confirms the presence of burials in this location. The survey also concluded that the modern road does not exactly match the contemporary road visible on the aerial images from the 1940s.

The survey also identified the presence of modern [looting] pits within the area of the probable grave.

It is likely that the northern memorial at this site is not directly situated over the grave, but the southern memorial certainly is partially over its location.

Selected figures from the full archaeology report are shown here, used with permission of the Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University:

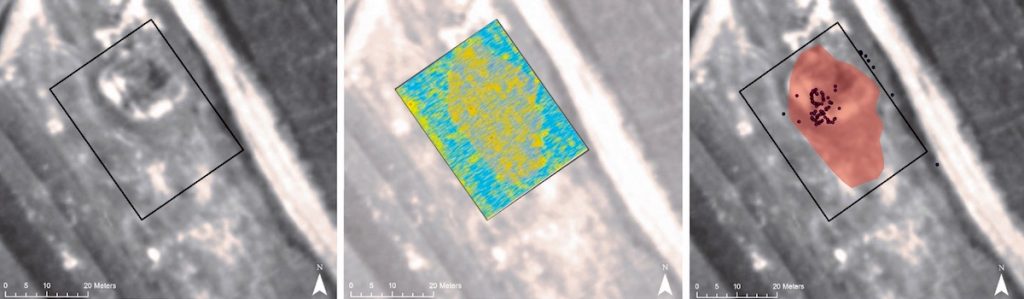

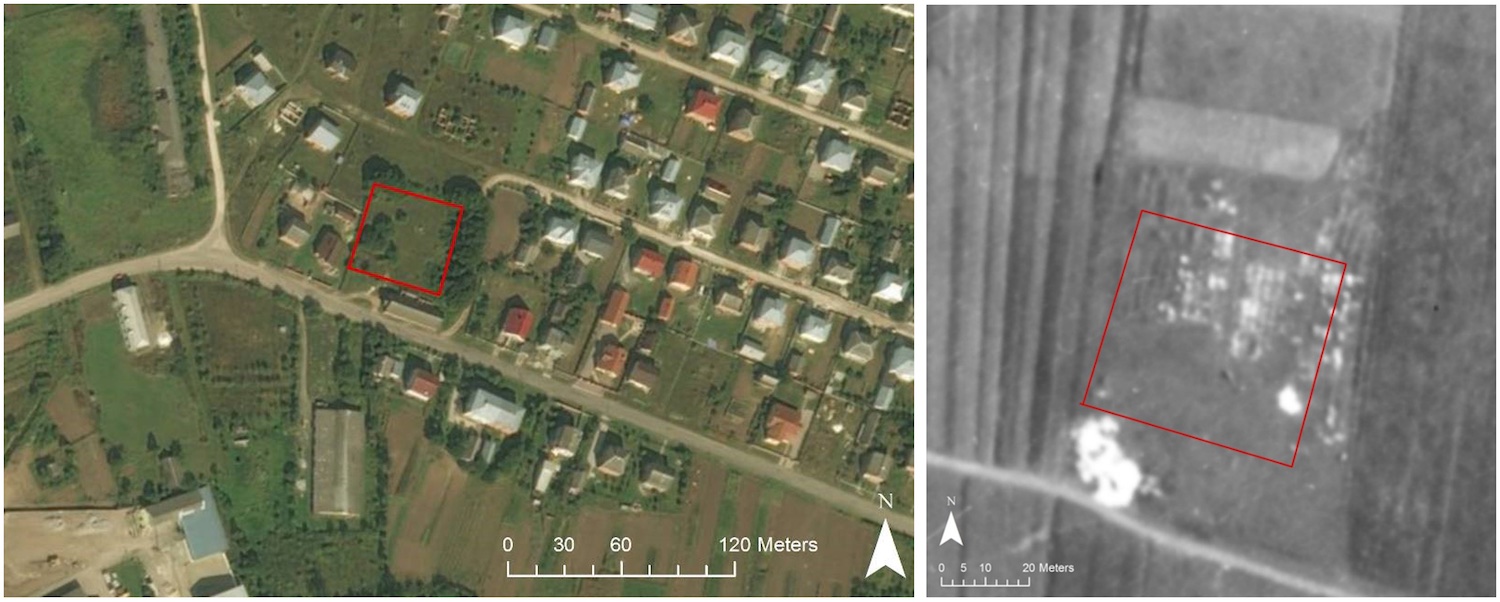

From Fig. 10: The area of investigation at the southern mass grave site (red rectangle) and the current memorials illustrated on a modern Google Earth image (left) and the 1944 Luftwaffe aerial image (right). On both images the black rectangle depicts the location of the smaller 30m by 39m GPR grid surveyed by the GSSI system. Copyright: Google Earth (left), US National Archives (right) and Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University (annotations).

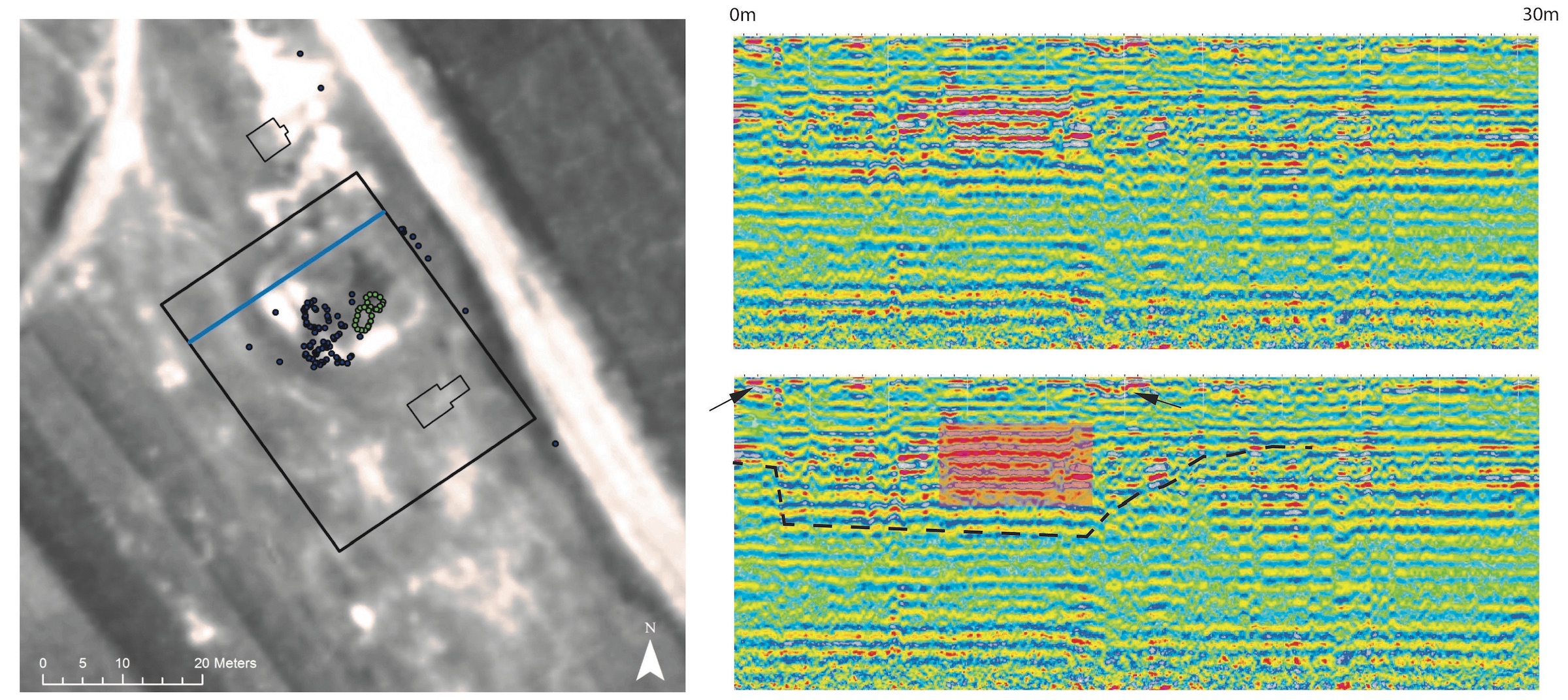

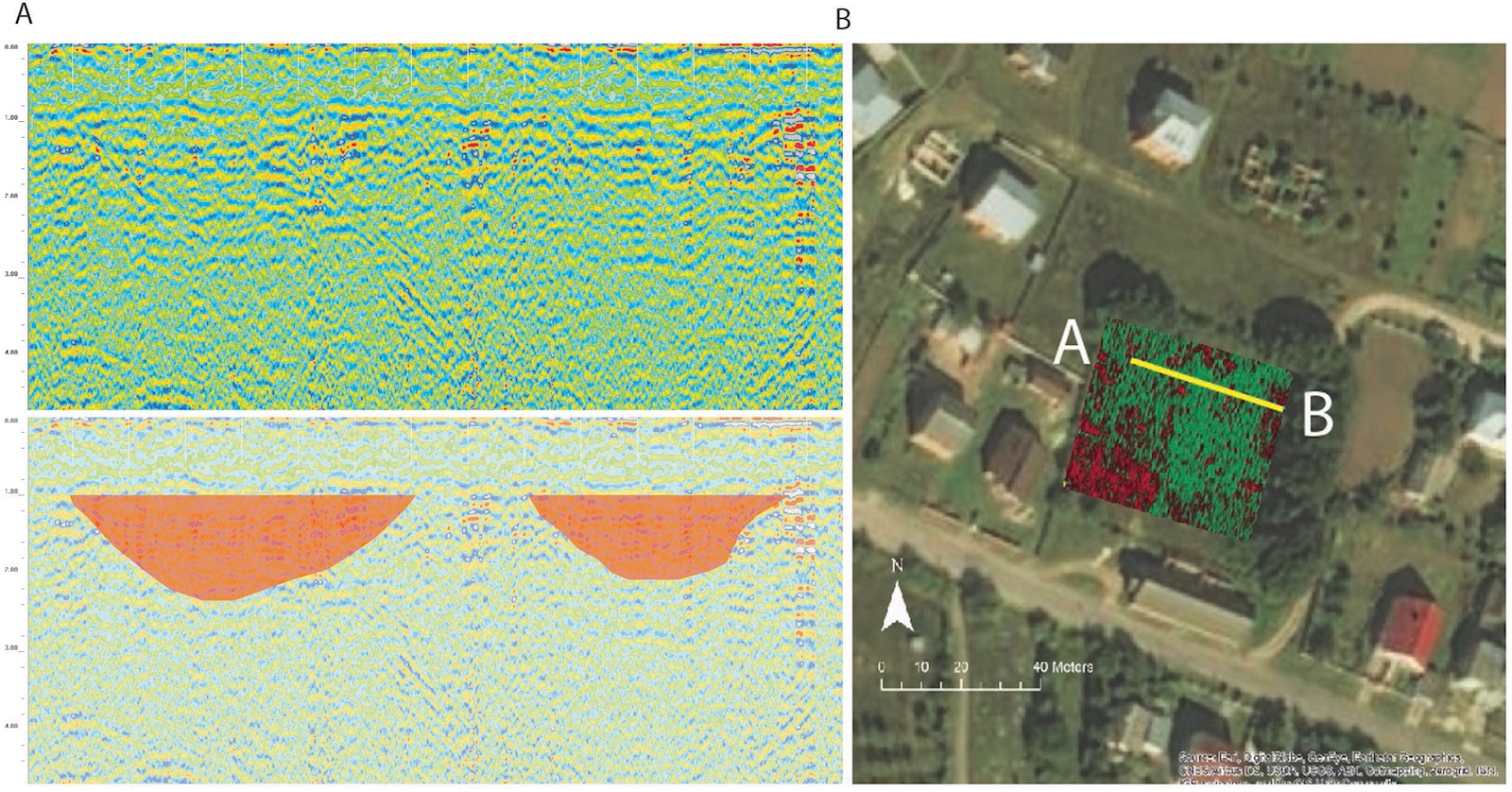

From Fig. 19: Section profile results from survey line 25m. The location of the survey line in relation to the 1944 image and the existing memorials (left), followed by the profile results (top right) and with annotation (bottom right). The two ditches visible at ground level are marked by the black arrows. Subtle signal responses forming a pit or trench was identified (black dash line) with an area of stronger signal response within this feature (red shading). Copyright: The Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University.

From Fig. 20: Section profile results from survey line 35m. The location of the survey line in relation to the 1944 image and the existing memorials (left), followed by the profile results (top right) and with annotation (bottom right). The location of previous looting holes are visible (black and white arrows) as well as the outline of a possible pit (dashed line) containing a layer or layers of compacted material (red shading). Copyright: The Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University.

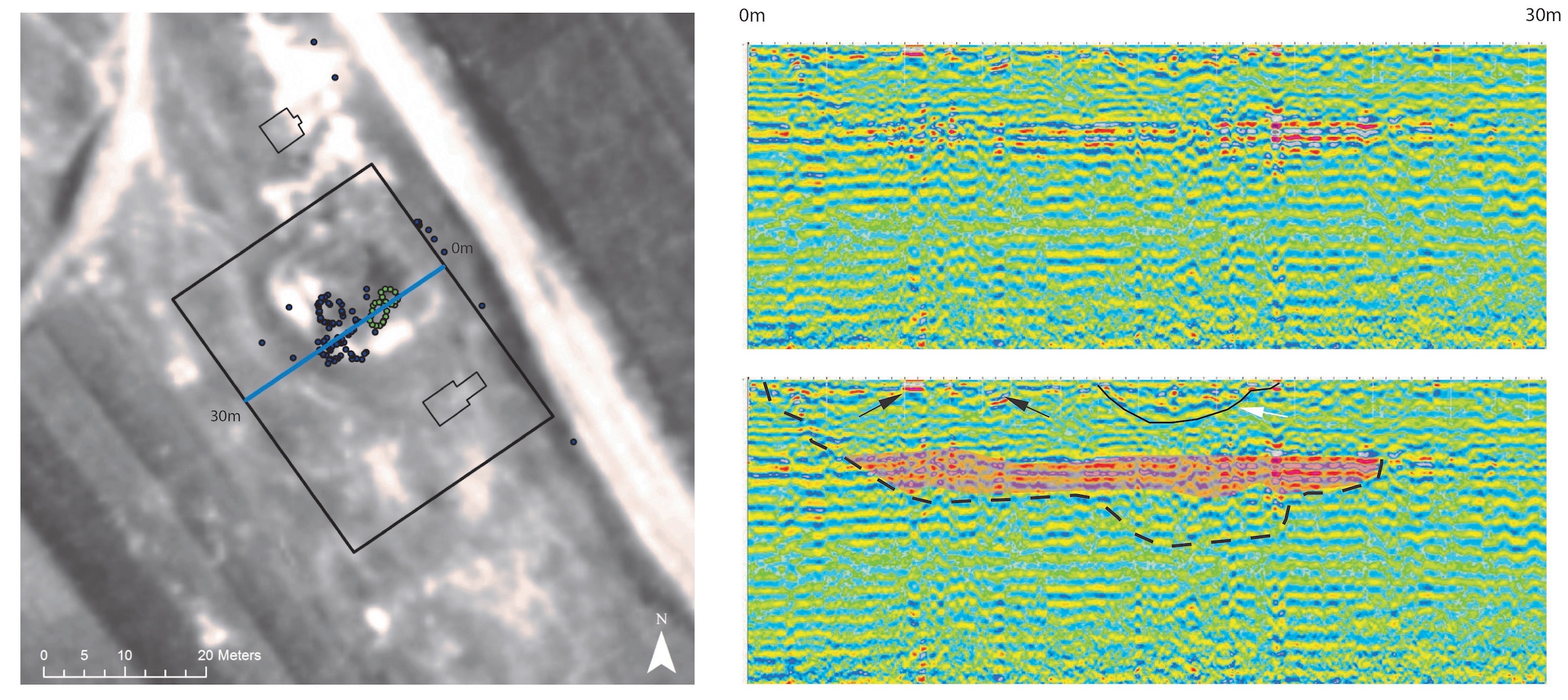

From Fig. 21: The time-slice (bird’s eye view) GPR data for the smaller GPR area at depths of 0.24m, 0.48m, 1.18m and 2.20m (top), repeated with interpretations (bottom). The possible grave is highlighted in light brown on the interpretative image. The red dots on the 0.24m and 0.48m depth slices represent looting holes. The smaller red dots on the 1.18m depth slice represent areas of compacted materials and could signify the beginning of the in situ layers of human remains. Copyright: The Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University and Google Earth (aerial image).

From Fig. 22: The 1944 aerial image with GPR grid (left), the time-slice (bird’s eye view) GPR data for the smaller GPR area at a depth of 2.20m (middle), and the annotated pit feature overlain onto the aerial image with the location of the surface human remains (right). Copyright: The Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University and Google Earth (aerial image).

As noted in the report, the GPR survey outside the central 30 by 39m grid area proved less successful, so the possible location and size of a second grave pit at the south site remains unknown, and an open and unresolved research question to be addressed in the future.

Human remains unearthed by earlier grave looting which were found on the site ground surface during the survey were documented (GPS locations and photographs) and then re-interred the same day in preexisting site holes using earth brought from outside the survey area, after consultation from the site with Rabbi Moyshe Kolesnik of Ivano-Frankivsk.

North Mass Grave (06~08 June 1943)

As for the south site, review of available historical documentation for the north mass grave site yielded no new precision or clarity in the testimony details, and because of the complex history of the site before and after the war, the document review was even more difficult. The “known” history of the site, just under a kilometer due north of the town square, at the large “vodokanal” and “near” the site of a former brickworks, containing the remains of some three thousand Jews (including survivors from Rohatyn but mostly from nearby towns and villages), killed on 06 June 1943 (and possibly over the next days), then buried in one or more pits, was as precise as the memoirs and testimonies allowed. No surviving Jewish witnesses of the killings or burials at this site are known, and due to the extreme danger for Jews in and around the town, none of the few Rohatyn Jews who survived in hiding visited the north site until after the Soviet army pushed the German army out of Rohatyn more than a year later. Thus no new or clearer information resulted from the pre-survey document analysis.

The survey team at work under a canopy of trees at the north site. Photo © 2017 Marla Raucher Osborn.

However, the archaeological evidence from the non-invasive radar survey, as detailed in the Centre’s full report (Appendix 1), is much clearer:

The forensic investigation at this site identified two buried features that most probably represent graves. The first is located behind the greenhouses close to the former quarry slope (Survey Area F). A long, trench-like pit exists at this location which measures 26m long and 4.5m wide. The feature limits goes beyond the survey grid and appears to run beneath the temporary animal shelters, and ends within survey area G. Therefore in total, this feature is potentially c.40m in length.

The second pit was identified beneath the current memorial in survey area G. As this is only visible in the 2D profile data, the dimensions can’t be ascertained at this time.

Further buried pit features were identified in areas A, F and G, but it is more likely that these are modern features.

Selected figures from the full archaeology report are shown here, used with permission of the Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University:

From Figs. 26 & 27: The GPR locations at the northern mass grave site. In order of data collection these are: Area A (blue); Areas B to E – greenhouse grids (black); Area F (yellow); Area G (red). In the close-up, the blue arrow marks the location of the current memorials on the site. Copyright: ESRI and Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University.

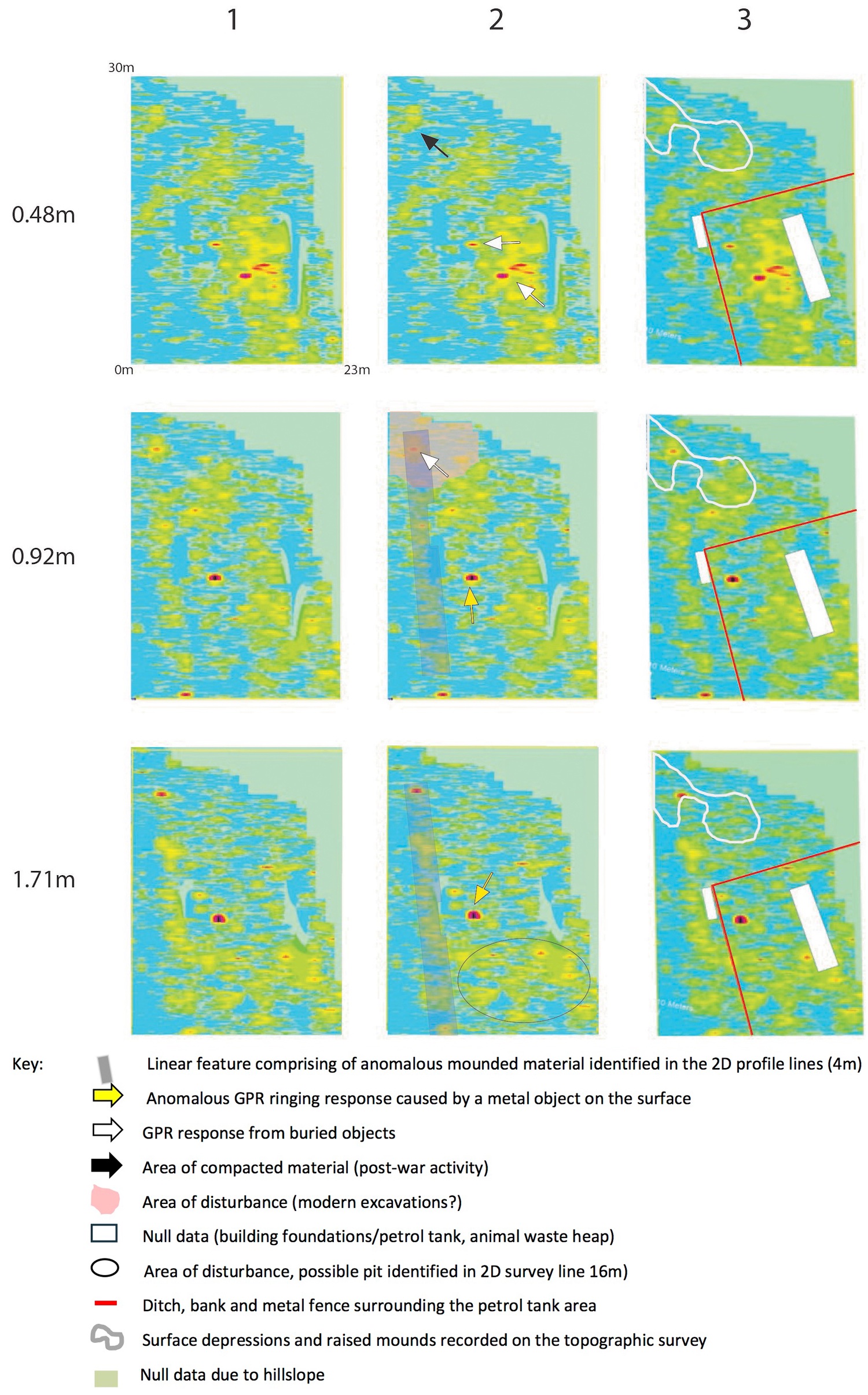

From Fig. 39: Time-slice (bird’s eye view) GPR data for Area F at depths of 0.48m, 0.92m and 1.71m (left column, 1), repeated with interpretations (middle column, 2), and timeslice data overlain by above ground features recorded during the topographic survey (right column, 3). Copyright: The Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University and Google Earth (aerial image).

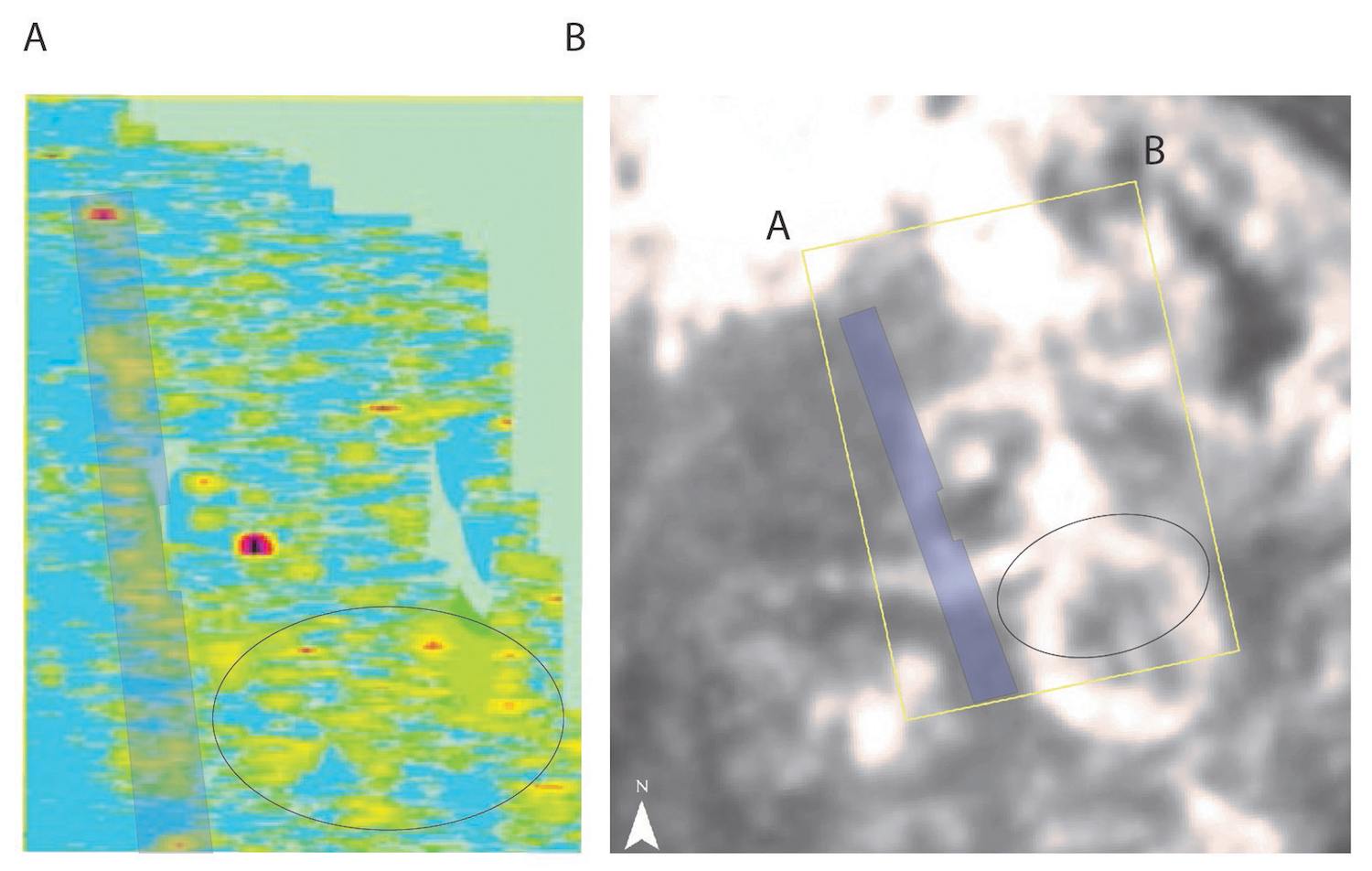

From Fig. 40: Timeslice data from 1.71m depth (left) showing the linear trench feature and an area of anomalous readings, with the location of the GPR grid and the features overlain onto the aerial image (right). Copyright: The Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University and Google Earth (aerial image).

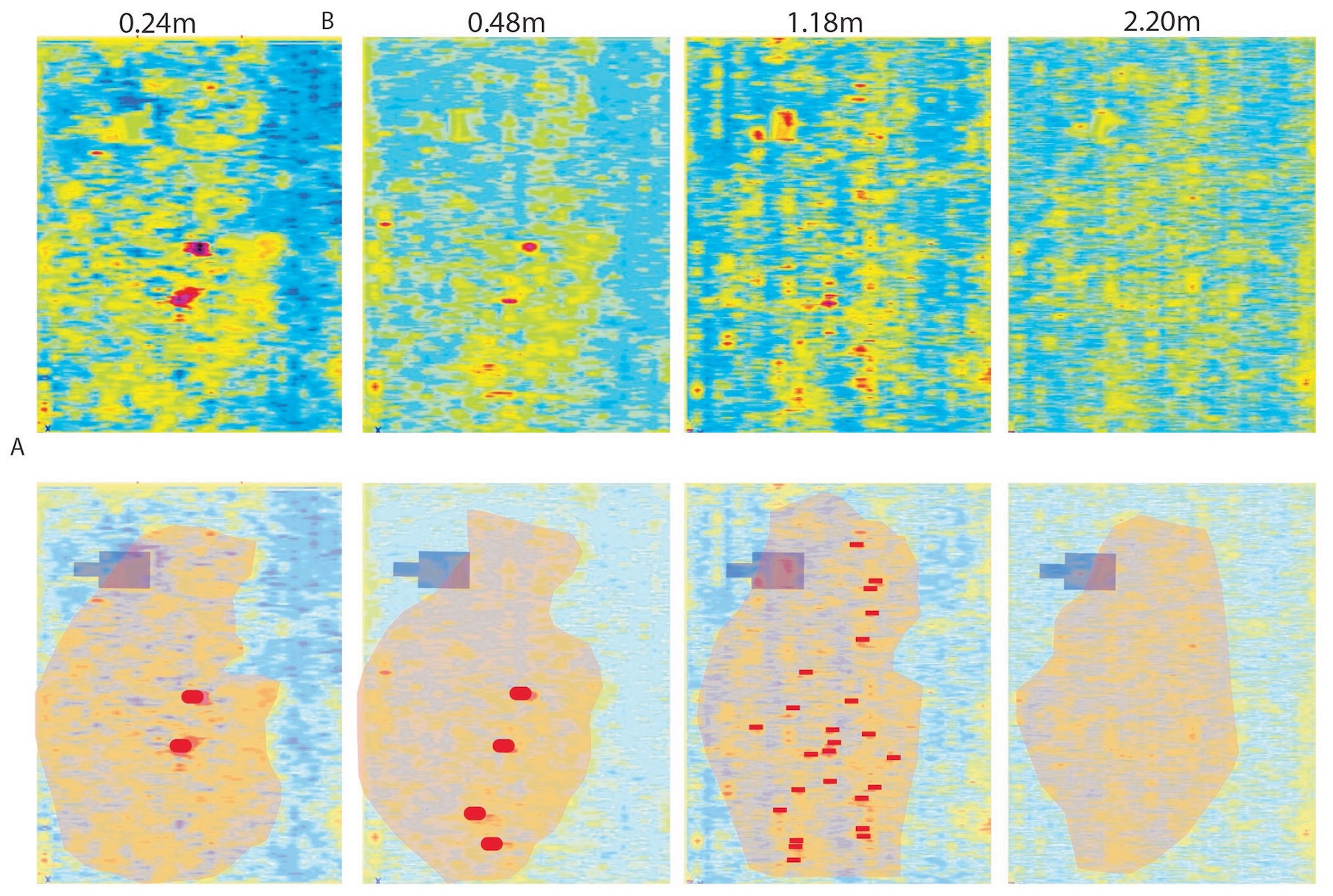

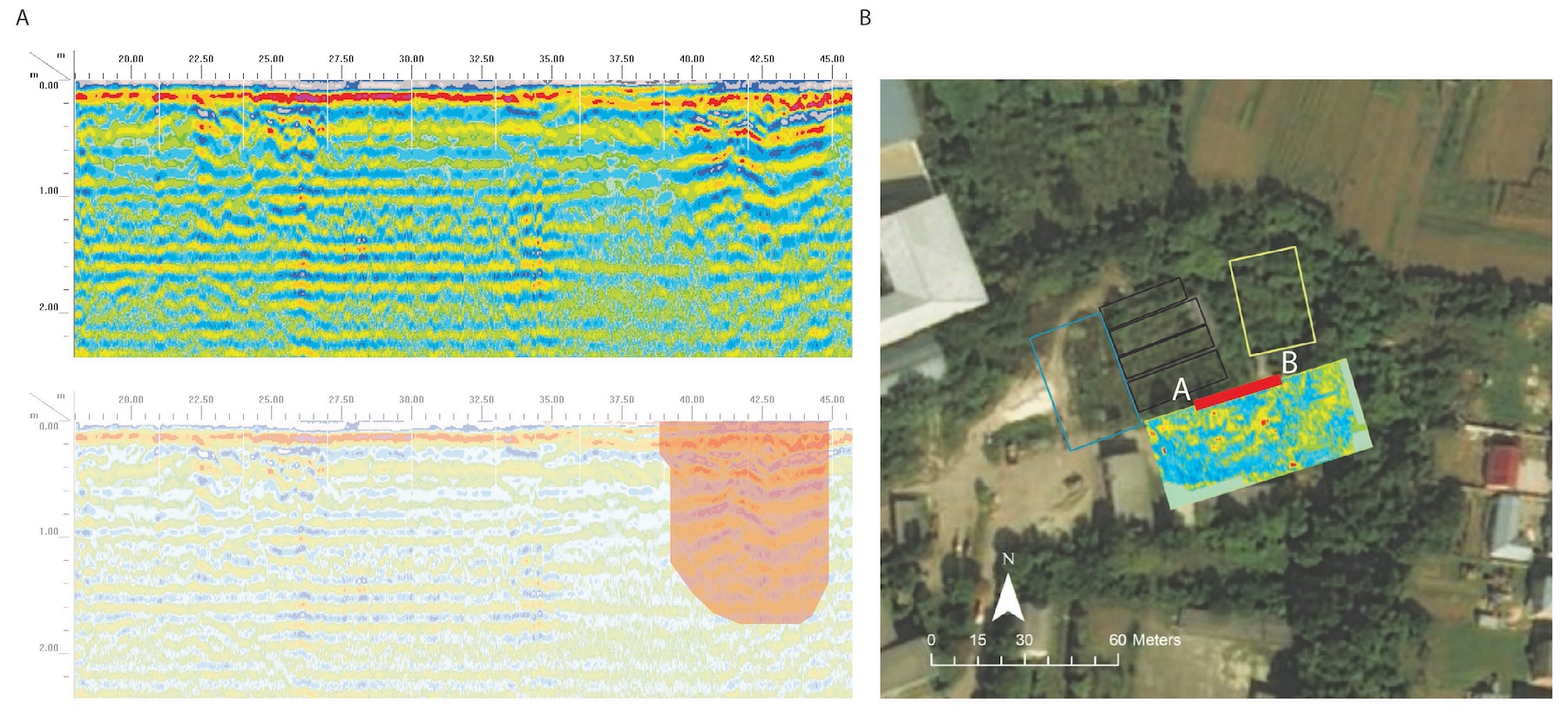

From Fig. 41: Section profile results from survey line 2 (1m) (top left) with annotation (bottom left) and survey line location (right). A profile of a possible pit feature is visible in the section (red). Copyright: The Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University and ESRI GIS base-mapping.

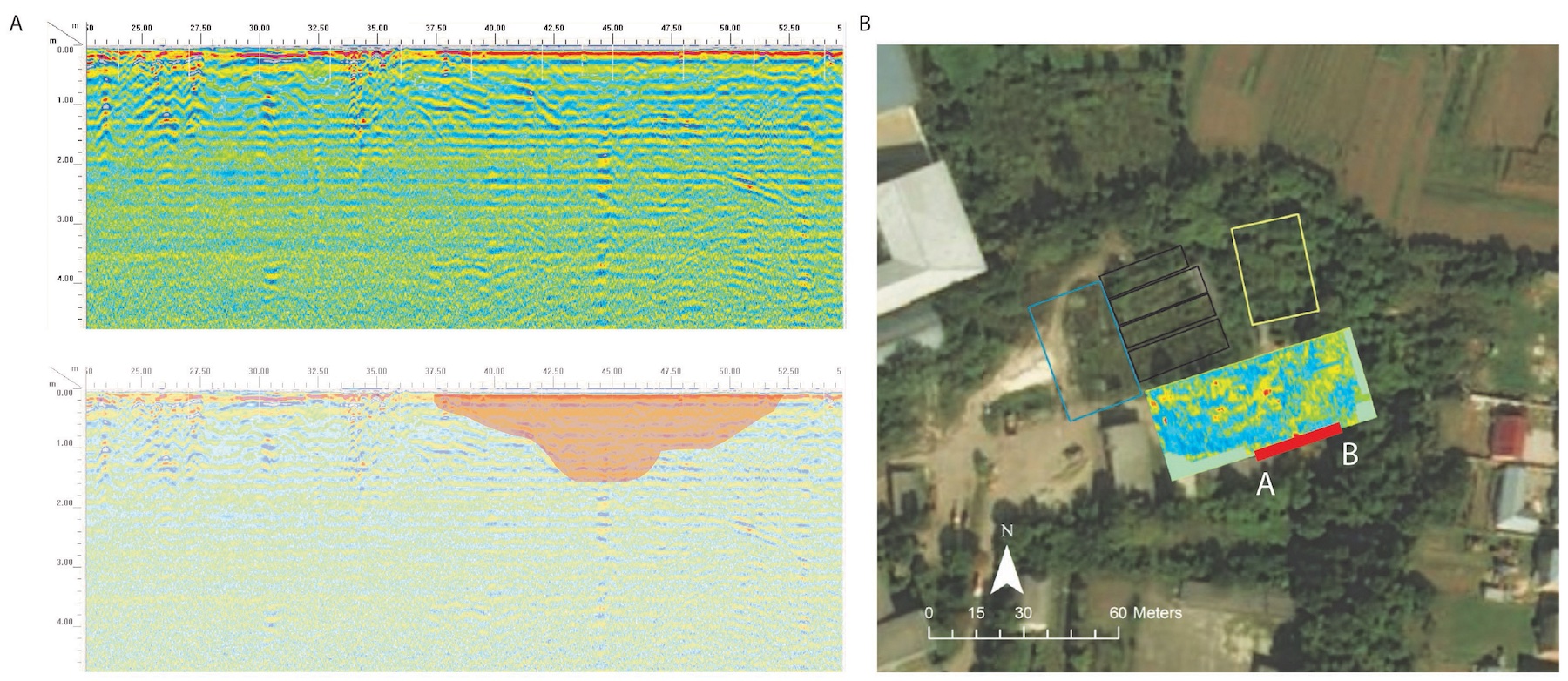

From Fig. 42: Section profile results from survey line @ 25m (top left) with annotation (bottom left) and survey line location (right). A profile of a possible pit feature is visible in the section (red). Copyright: The Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University and ESRI GIS base-mapping.

From Fig. 43: Timeslice (birds eye view) GPR data for Area G at depths of 0.5m and 2m (top), repeated with interpretations (bottom), and an area photograph and grid location (right). Copyright: The Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University and Google Earth (aerial image).

Combining the timeslice data from Areas F and G enables a visual bridging of the probable grave feature which connects both areas:

From Figs. 27, 28, 39, and 43: Composite image of timeslice (bird’s eye) GPR data for Area F at 1.71m depth plus Area G at 2m, showing continuity of the feature across the areas. Copyright: The Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University and Google Earth (aerial image).

In addition to the findings of probable grave features in Areas F and G, the archaeological evidence significantly suggests there are no probable wartime graves in Area A (the rubbish transfer area) and in Areas B~E (the greenhouses); although caution is always warranted in development around known mass graves, this finding effectively clears those areas for further development by the City of Rohatyn.

As for the south site, the results of the radar survey at the north site are limited to the areas actually scanned, which are smaller in scope than the original survey plan due to ground preparation issues ahead of the site work. Given the scarcity of historical documentation of events at this location and the uncertainty about the number of grave pits in the area, caution should be exercised in any development work where no archaeological data yet exists.

New Jewish Cemetery

Both Jewish cemeteries in Rohatyn were desecrated during the German occupation, by removal of nearly all of the gravestones for use as building material. No clear witness accounts testify to wartime mass killings at either of the Jewish cemeteries, and few historical or recent testimonies suggest the cemeteries were used for mass burials following any of the major aktions. However, after Rohatyn’s Jews were confined to the ghetto, many witnesses tell of their rapidly rising death rate due to hunger, typhus and other diseases, and shooting by police and military. These large numbers of dead required burial; several memoirs and testimonies tell of burial “in the Jewish cemetery” without specifying which cemetery, but because the old cemetery had closed in the 1920s due to overcrowding, we presume the ghetto burials were primarily in the new Jewish cemetery. Given the death rate and living constraints, many of those burials may have been in one or more mass graves.

The Jewish cemeteries in Rohatyn are fenced and remain protected by the City, so the non-invasive survey at the new cemetery was commissioned only in an effort to improve the historical record about that site for possible future memorial markers or signage. Several of the Jewish memoirs of life in Rohatyn described deaths of family members in the ghetto; it may help to provide closure if their likely resting place is known.

By agreement with the Centre of Archaeology at Staffordshire University, the survey at Rohatyn’s new Jewish cemetery forms part of a PhD project led by one of the archaeology team members, and the research data for this site will be included in her thesis in about a year. Thus no conclusions about the site are included in the current full report, but several features of interest are illustrated and interpreted from provisional analysis of the GPR data, comparison to the 1944 aerial photo, and walkover survey observations.

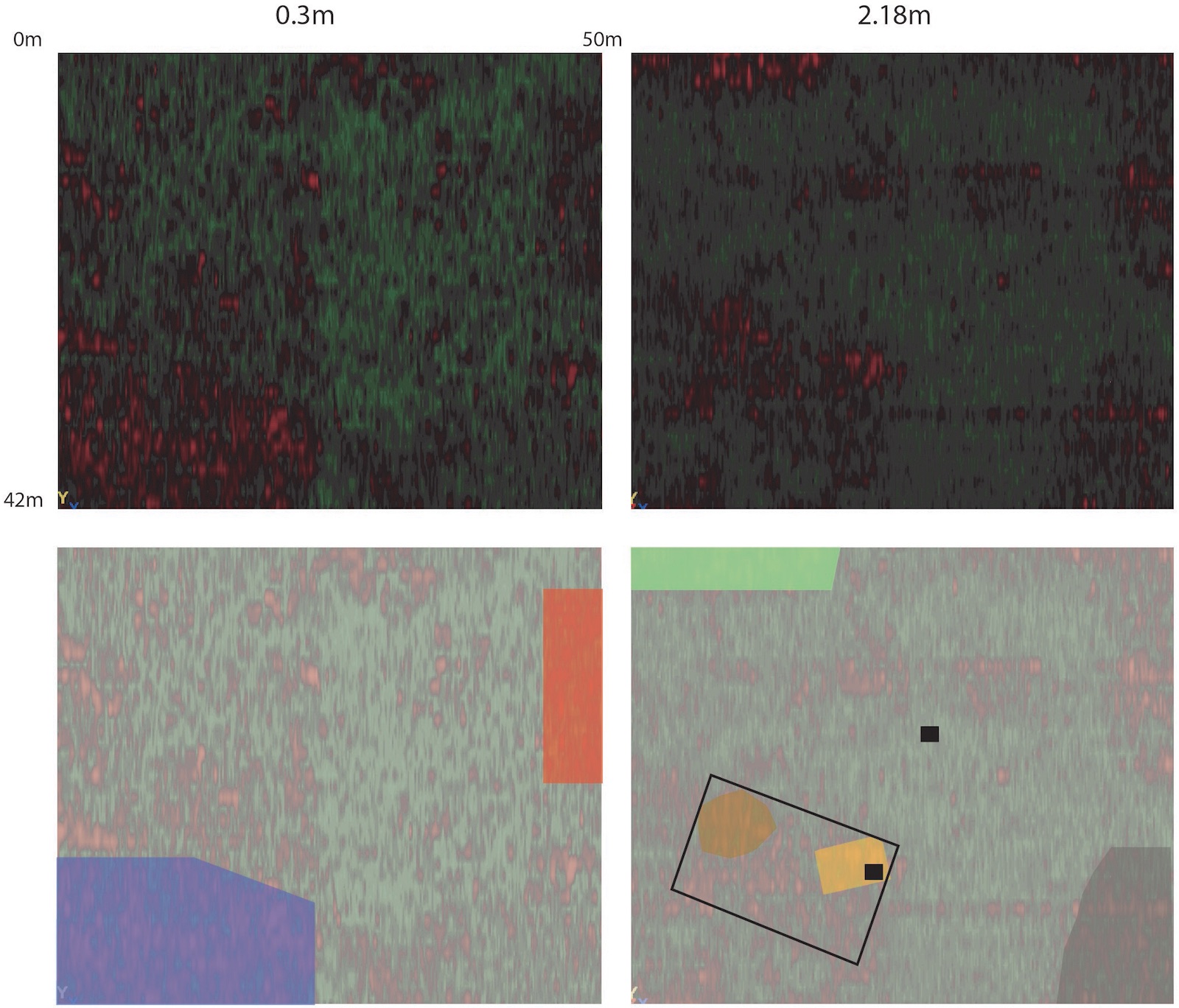

Included in the tentative results are two possible pits; additional features needing further study include an area of vegetation change (which suggests different subsurface materials) and a rectangular anomaly in the GPR data enclosing one of the possible pits. Selected figures from the archaeology report are shown here, used with permission of the Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University:

From Figs. 47 & 49: The GPR grid location at the New Jewish Cemetery site (red rectangle) illustrated over the current Google Earth image (left) and over the 1944 aerial image (right). Copyright: The Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University and Google.

From Fig. 51: 0.3m and 2.18m timeslice plot of the new cemetery site (top), with feature annotation (bottom). The feature interpretations are: concrete (blue), vegetation change (red), area of general disturbance (grey), area of ringing from modern fence (green), memorials (black squares) two possible pits (brown and yellow) and a rectangular anomaly (black outline). Copyright: Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University.

From Fig. 52: Section profile results from survey line 9m (left top) with annotation (left bottom) and survey line location (right). The profile of 2 possible pit features are visible in the section (red) Copyright: The Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University and ESRI GIS base-mapping.

As noted in the report, from analysis still in progress, early indications are that individual graves are identifiable within the data, some located beneath visible matzevot, others with no marker stones. Thus, from the 1944 aerial photo and the recent GPR work, in the future it may be possible to create a partial reconstruction of the new Jewish cemetery grave map.

Survey Issues

Working around debris, vegetation, and other obstacles at the north site.

Photo © 2017 Marla Raucher Osborn.

The non-invasive archaeology survey was hampered by several issues before and during the GPR work, which impacted both the quantity and the quality of the measurement data. Despite best efforts in preparing the three sites for the survey, none of the sites was adequately cleared of vegetation and debris; ground surface materials, especially metals, interfered with clear radar signal reception. In many areas, the rough terrain and stumps of woody shrubs caused the antenna to pitch and jump during sweeps, disrupting coherent association of signals with locations. Some intended survey areas were not cleared at all of agricultural crops, wild vegetation, construction debris, or other obstructions, and were inaccessible to the radar. Each of these issues will need to be addressed and mitigated in site preparation for any future surveys.

One other GPR issue will require a different approach in future surveys: The archaeology team has indicated that the high clay content of the soil in the region is very reflective of radar signals and causes significant “background noise” in the measurement data, which both masks subterranean features and blurs the detection of subsurface feature edges and depths. The team suggests that GPR may not be suitable for future research at the sites, with ground resistance survey tools and methods perhaps being the best alternative; see sec. 7.2.2 of Holocaust Archaeology in the References below.

Other Issues

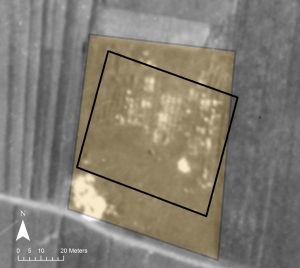

From Fig. 46: The present boundary of the new Jewish cemetery (black outline) overlain onto the 1944 aerial image showing the original limits of the cemetery boundary (yellow shading). Copyright: The Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University.

Two important issues independent of the radar work were exposed by pre-survey GIS analysis and by site walkover surveys performed by the archaeology team. The first pertains to the dimensions of the new Jewish cemetery in Rohatyn. During their GIS analysis of the cemetery using the 1944 aerial photo, the archaeology team concluded that the current fenced perimeter of the cemetery does not align with the visible cemetery boundaries in 1944, and the current area of the cemetery is smaller than it was in 1944. Although the reduction in cemetery area is not necessarily a heritage problem, as there may have been no pre-war or wartime burials outside the current perimeter, the City of Rohatyn should exercise caution before any development is permitted within the original boundaries of the Jewish cemetery (e.g. non-invasive survey of proposed areas outside the current cemetery fence should be performed before permits are granted). RJH will provide a copy of the 1944 aerial photo to the City for their own GIS analysis of this issue.

Evidence of looting at the south site in 2012, and collapse of the hole cover in late 2017. Photos © 2012 and 2017 Jay Osborn.

The second issue is the presence of ongoing looting of the south mass grave site by unknown perpetrators. Evidence of this criminal activity was first noticed by RJH and colleagues in 2012, but at the time we believed the grave pit(s) were located in a different direction from the memorials, and there were no visible spoils; the open hole was filled or covered soon after, and the site seemed secure for the next years.

However, during their walkover survey in May 2017, the archaeologists found the site had been disturbed again: loose soil and human remains (bones) plus clothing fragments and a bullet casing were strewn on the ground surface on and around the same hole, which had been lightly covered by thin material (cardboard or similar) and earth. In all, nearly one hundred bones or fragments were recovered from the ground surface, documented, and re-interred by the archaeology team and RJH, under the guidance of Rabbi Kolesnyk of Ivano-Frankivsk; bones which were partially embedded in the soil were left untouched and covered with fresh soil. These remains provide stark proof of the mass grave underneath, but their removal represents a desecration of the wartime burial place.

Even after the site survey, evidence of continued looting at the site was found later in 2017, and by December 2017 the cover over the looting hole had collapsed, leaving the hole exposed to animals and further looting. Because of the remote location of the south mass grave, it is vulnerable to covert criminal activity. We need to open a discussion with the City of Rohatyn about how best to strengthen the legal protection of the site, how to enhance monitoring of the site by police, and perhaps how to enhance the physical protection of the graves.

Future Work

Observing the 75th anniversary of the 20 March 1942 aktion at the site. Photo © 2017 Jay Osborn.

The Rohatyn Jewish mass graves archaeological research in 2017 fell short of the original goals, for a variety of reasons described above. In particular, the geographic extent of the survey areas was significantly smaller than originally intended, and it is possible or probable that additional grave pits exist outside of the survey grids at both known mass grave sites; one or more further grave pits may also exist outside the fenced perimeter of the new Jewish cemetery. The high cost of non-invasive archaeological research and the significant preparation time and logistical demands associated with the work together mean that RJH cannot easily organize a return to this research in the near future. Further work of this type will be considered and, if feasible, reported in the coming years; these sites will forever be essential elements of Rohatyn’s Jewish heritage.

Related work, for example to enhance protection of the south mass site, and to mark and commemorate the mass grave boundaries identified in this year’s research, will likely begin sooner, and will also be reported as part of our mass grave memorials project.

References

Final Survey Report (Centre of Archaeology, Nov 2017): English / Ukrainian

Survey Proposal (Centre of Archaeology, Jul 2016): English / Ukrainian

Request for Proposal (RFP) (Rohatyn Jewish Heritage, Jun 2016): English / Ukrainian

Initial site survey planning maps (Centre of Archaeology and Rohatyn Jewish Heritage, Apr 2017)

Holocaust Archaeology: Archaeological Approaches to Landscapes of Nazi Genocide and Persecution, Caroline Sturdy Colls, in the Journal of Conflict Archaeology, Vol. 7 No. 2, 2012, p. 70~104. [in English]

Learning from the Present to Understand the Past: Forensic and Archaeological Approaches to Sites of the Holocaust, Caroline Sturdy Colls, in Killing Sites Research and Remembrance, International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, IHRA series vol. 1, 2015, p. 61~78. [in English]

Data and Images

More complete data and images from the survey measurements and analysis are currently being assembled by the Centre of Archaeology for transfer to Rohatyn Jewish Heritage. When that data is available, we will share it with City of Rohatyn engineers and staff.

Acknowledgments

Rohatyn Jewish Heritage wishes to acknowledge and thank the many individuals and organizations who contributed time and funding to this effort and to resolving the many small and large issues which were encountered throughout the project, especially just before and during the site survey in Rohatyn. We do not even know the names of everyone who helped us out of kindness; please forgive us if we have failed to mention every name.

The Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University The City of Rohatyn Lviv Volunteer Center of the All Ukrainian Jewish Charitable Foundation “Hesed-Arieh” Rohatyn District Research Group Vasyl Yuzyshyn Sasha Nazar Vitaliy Nadashkevych Rabbi Moyshe Kolesnik Mykola Shynkar Vasyl Myts Olha Blaha-Maletska Ruthy Erez Thomas Traber Alex Feller Alex Denisenko Serhii Nasalyk Viktoriia Sergiienko Halina Bohun Jeremy Borovitz David Kidron Caroline Sturdy Colls Kevin Colls Dante Abate Czelsie Weston Marina Faka Nancy Siegel Etienne Denneboom Tammy Hepps Cheryl Morden Michael Bohnen Yisrael Schnytzer Erín Moure Chaya Rosen Yossi Chajes Alan Mandelberg Ihor Muryn Sharlene Basch Andrea Tzadik Benjamin E. Cohen Morey Altman Eleanor Raucher Joe Bratspis Anna Cwirko-Godycki Jonnie Schnytzer Rachel McRae Neil Schwartz Mykhailo Vorobets Stephan Small Peggy Tutone Janis Kirtz Richard Loring Zahara Solomon Leah Gilbert Penny Schwartz Sonja Greckol Łukasz Biedka Kyle Logan Paley Lewis Katie David Edward Janes Denni Gershaw-Smith