![]() Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Ця сторінка також доступна українською.

Introduction

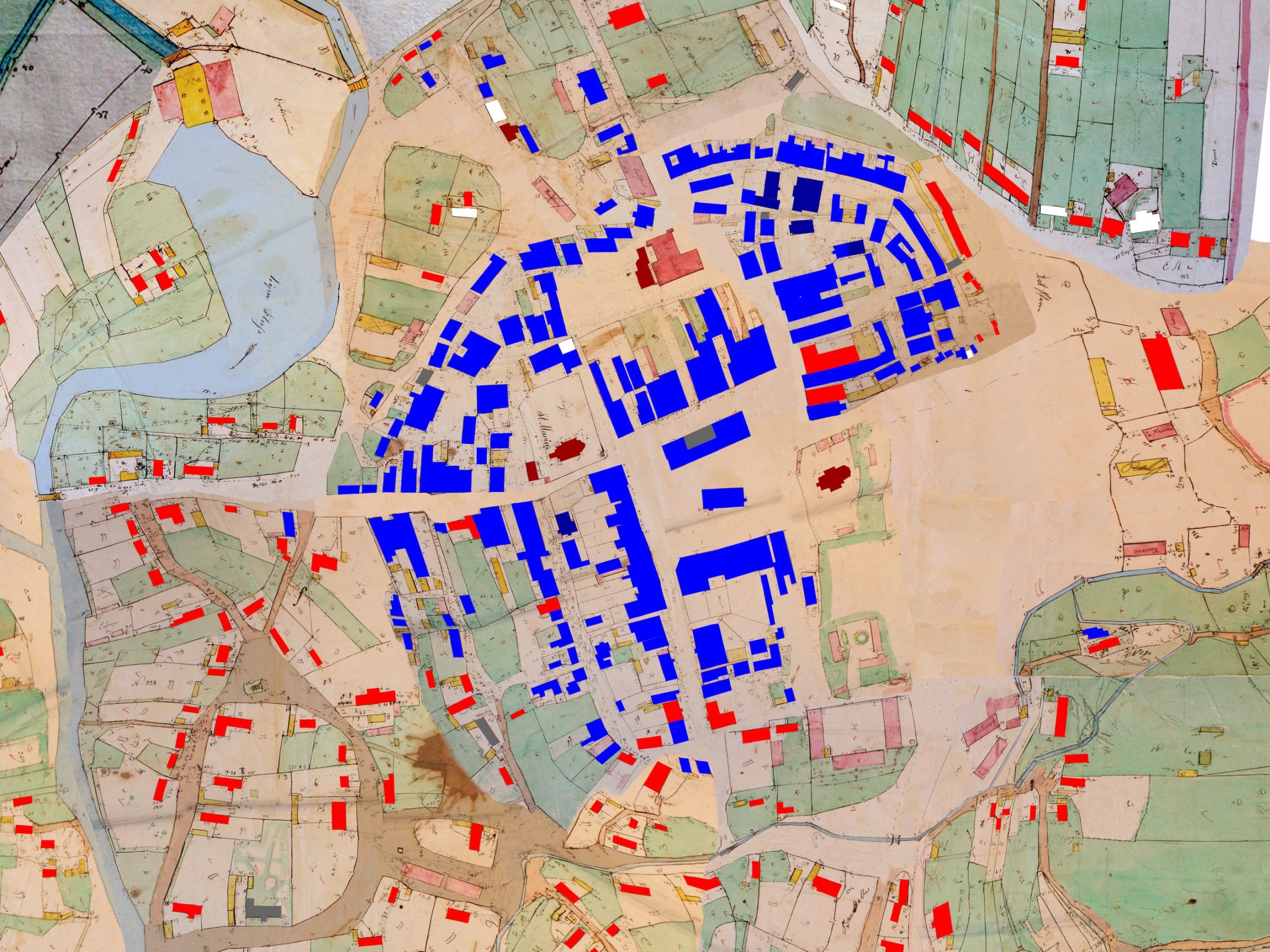

Click the image above to open the interactive map in a new window. The color key and other information is below on this page.

This article presents a modern analysis of historical records in order to map where the Jewish community of Rohatyn lived in the mid-19th century. Many genealogy researchers have paired vital records of births, marriages, and deaths with cadastral (property tax) maps to locate where individual families lived in the past; for example, a very detailed family history map of Rohatyn was assembled and published a few years ago. The data, analysis, and mapping described on this page graphically represent community history, visually depicting neighborhoods of Rohatyn where Jews and gentiles lived mostly among their own religious groups, and other neighborhoods where the residences were more mixed. (The term “gentile” is used here as a neutral term for all non-Jews based on both ethnic and religious identity.)

One motivation for conducting this study is the long-standing idea that Jews in Rohatyn lived a “Jewish neighborhood” or “Jewish quarter”, especially before the 20th century. This is a concept inherited from other places, including from other settlements in the former Kingdom of Galicia where Jews may have lived in different economic, legal, and religious circumstances than the community of Rohatyn which thrived for more than three centuries. We have been studying the Jews of Rohatyn and their physical heritage for more than a decade, and even we were somewhat surprised by the analysis results; we guess that others will be surprised as well.

The map is a simplified snapshot in historical time of an evolving community characteristic, based on one of the most complete data sets available for Rohatyn, as described below. Similar snapshots could be made for other specific times or periods, and perhaps even to depict the evolution of neighborhoods over time, however in our estimation the data available for other historical times is much less complete and the resulting analysis could proceed only with significantly less confidence in the accuracy of the representations. Still, we can hope that more data will become available over time.

This article is part of a series on Rohatyn’s immovable Jewish heritage on this website, and is also part of the project Mapping Rohatyn: Geography as a History Resource.

Methodology

Two views of the map overlay: the georectified 1846 cadastral sketch (top),

and the satellite image (bottom). Both views show a portion of the town square and the St. Mary church. Images © Gesher Galicia and Bing.

The analysis presented here uses as its base an 1846 cadastral field sketch of Rohatyn prepared by agents of the Habsburg Monarchy in the first pass of a very detailed land survey and property value assessment which would ultimately produce a remarkably accurate high-scale lithographed map of the small city; that accurate map has not survived in archives, leaving only the rough initial sketch for modern use. Because the basic geographical structure of Rohatyn has not changed significantly since the 19th century, a partial georectification of the distorted field sketch was possible, which the Jewish genealogy organization Gesher Galicia (GG) undertook for its digital Map Room in 2011 using photographs funded by the Jewish family history organization Rohatyn District Research Group (RDRG) of the original sketch sheets preserved at the Ukrainian Central State Historical Archives in Lviv (TsDIAL). Rohatyn Jewish Heritage (RJH) published an interactive overlay of the historical map on modern satellite images in 2016. Note that this map excludes the adjacent village of Babintsi which had its own legal cadastral area and map in 1846 (that map has not yet been found in archives); Babintsi was incorporated into Rohatyn some decades later.

As seen on the detailed historical field sketch, every building in Rohatyn was represented by an outline of the building’s footprint on the earth, and typically colored to indicate the materials of construction (one way the structures were valued for tax purposes): pink for masonry, i.e. stone or brick, and yellow for less-durable materials, typically wood. Identifying “home addresses” on the historical map is relatively easy for field sketches like this one: the house number (an older form of address) of each house is written directly on the house outlines, or if not on then nearby in a place which makes association with a particular house assured. In 1846 the majority of buildings in Rohatyn were houses (i.e. residences) though religious community buildings e.g. churches and synagogues plus non-residential parish buildings and schools are also shown (without house numbers), and one can see local civic and imperial military storage structures as well as a large number of farm outbuildings e.g. stables and other storage (again without house numbers).

This is important because nearly every historical record about individual people in 19th-century Galicia is tied to their address – their house number. At the time of the 1846 land survey associated with this map, property registers (tabulated multi-page text records) were also assembled which identified the owner of each building and each land parcel; the registers linked owners’ names with their numbered parcels (not shown on this map) and their house number, i.e. where they lived. Privately-owned houses were included, as were imperial and community-owned non-residential buildings as mentioned above. Fortunately for Rohatyn a complete set of property registers has survived from 1846, giving a nearly comprehensive listing of individual owners and the buildings they owned. Unlike in larger cities, for Rohatyn (estimated total population around 4000 in 1846) the property records show an almost 1:1 relationship between owners and house numbers, strongly indicating that most families lived in houses they owned; this encourages the use of the property registers as “address books”.

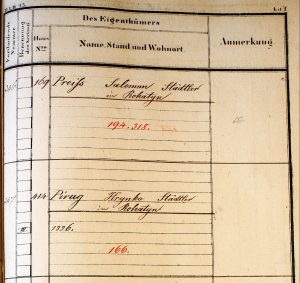

A page from an 1846 property register of Rohatyn, showing the building owners Salomon Preiss and Hrynko Pirug (Pyrih) with their house numbers and property numbers. The clerk sometimes struggled with Ukrainian letters and names, and spelling is variable throughout the register. Image from TsDIAL courtesy of Gesher Galicia.

The RDRG and GG have researched, acquired, and indexed copies of a wide variety of other historical records about individuals which can supplement the 1846 property registers. Apart from an 1820 property register (the so-called Franciscan survey, which is incomplete and only partially matches the 1846 field sketch), most of the other data was gathered from Polish state archives and was recorded by the 19th-century Rohatyn Jewish community, so omits gentile individuals and families. Some of this data can still be valuable for filling in the rare gaps in the 1846 property data, for example if other records show the same surname associated with a specific house number in years before and after 1846 but no 1846 property data exists. See the Resources section below for a listing of specific records and their sources as used in the analysis presented here.

Using these same records and the same map, in 2018 a joint effort by GG, the RDRG, and RJH produced an interactive data map for Rohatyn (as part of a pilot project for several Galician places) which shows all of the available records (not only for 1846) linked to individual houses. Although the linked data is incomplete, the data map can be a useful reference for studying how individual houses changed residents over a time span of up to six decades.

With a key established which links house numbers to the names of historical residents, the next step in this analysis was to link individual names to one of the historical communities in Rohatyn. Ordinarily it can be challenging to use names to identify religion and/or ethnicity, however the 1787 decree (“Das Patent über die Judennamen“) of Habsburg Emperor Joseph II requiring all Jews in the empire including in the Kingdom of Galicia (where Rohatyn was) to take Germanic surnames resulted in the development of a sharp distinction between Jewish and Slavic surnames in the 19th century. Research by the RDRG and RJH shows that clear naming patterns and family lines in Rohatyn persisted significantly from the 19th century to the present, or in the case of the Jewish community until the Holocaust and then to the present group of Jewish descendant and survivor families researching their ancestors. No doubt a few names linked to the hundreds of houses on the historical map were assigned in error, but immersion in early Rohatyn Jewish records, Jewish Holocaust victims lists, and the modern gentile community of Rohatyn makes matching communities to 1846 surnames names very strong, and patterns of given names often reinforces or clarifies initial assignments.

For example, surnames found in the 1846 property records (usually in German or Polish spellings) which also appear in other Jewish records and Holocaust victims lists include such well-known Rohatyn names as: Altman, Aufrichtig, Bader, Barban, Bratspis, Cigler, Dub, Einstos, Faust, Garten, Glanzberg, Gold, Goldschlag, Haber, Hader, Horn, Katz, Kirschen, Langer, Leichtling, Löw, Nagelberg, Preiss, Scher, Schnekraut, Stratyner, Teichman, Wald, Weiler, Weisman, Willig, and more.

Gentile surnames appearing in the 1846 records (often in unaccented Polish spellings) and known today in Rohatyn or in émigré communities through RJH contacts, social media, and current local newspapers include: Baczynski, Bilinski, Boykiewicz, Czarnecki, Demczyszyn, Dzera, Hural, Jankiewicz, Kapral, Krasiński, Kucharz, Kupiak, Lalka, Lewicki, Loboda, Malecki, Nosyk, Okrepki, Pirig, Sikorski, Sliwka, Slusarz, Smerklo, Szmigel, Terebuszka, Tymkow, Wereszczynski, Worobiec, Zamoszczak, Zenczuk, and more.

An example of coloring of numbered houses on the 1846 cadastral map based on names in the registers. Images © Gesher Galicia and RJH.

It was not possible in this analysis to confidently associate gentile names from 1846 with specific historical or current Christian religious communities in Rohatyn, or with any of the non-Jewish ethnic groups known to be present in Habsburg-era eastern Galicia (Ukrainian, Polish, Austrian, German, etc.). Some reasons include the rendering of Ukrainian names in Polish form by surveyors, the rendering of both Ukrainian and Polish names in German form by Austrian authorities, past and current mixing of families with Ukrainian and Polish ancestry and different Christian religious identity, etc. Similarly, no attempt was made here to associate Jewish names with any of the different Jewish religious movements known to have been active in Rohatyn, including Hasidic, Orthodox, and more liberal groups within Judaism. Memoirs and testimonies of both Jews and Ukrainians who lived in Rohatyn in the first part of the 20th century assert that mixed marriages of Jews and gentiles were extremely rare, and we feel it is reasonable to extend that rarity back in time to 1846.

With these acknowledged limitations, it was possible to assign certain or very likely community identity (Jewish or gentile) to more than 98% of the named resident house owners in Rohatyn in 1846. On the map, numbered residential buildings were outlined and filled with pure colors to stand out in contrast to the existing map colors which indicate building materials or landscape features; non-residential religious buildings were filled with darker shades of the same colors. The colors were arbitrarily chosen as:

![]() blue: private Jewish home

blue: private Jewish home

![]() red: private gentile home

red: private gentile home

![]() dark blue: non-residential Jewish community building

dark blue: non-residential Jewish community building

![]() dark red: non-residential gentile community building

dark red: non-residential gentile community building

![]() grey: private home without clear community association

grey: private home without clear community association

![]() white: numbered house without ownership/residence data in or near 1846

white: numbered house without ownership/residence data in or near 1846

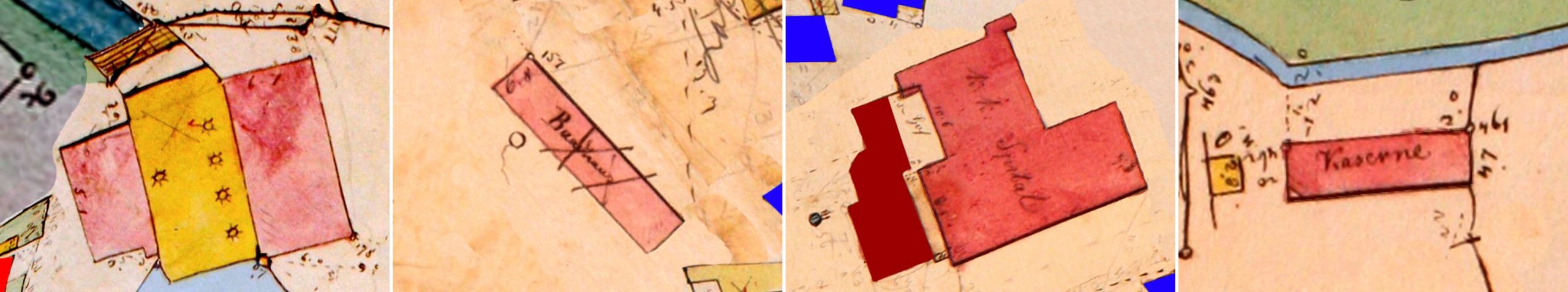

A number of buildings on the map which are not numbered, and which are labeled with purposes which cannot be confidently linked to one of the religious communities, are not colored. This includes two of the bath houses, the large mill, plus an Austrian imperial hospital and several military barracks (kaserne) buildings. As noted above, merchants’ storage warehouses and farmers’ outbuildings are similarly not colored on the map. A few examples are shown in screenshots here.

Unnumbered but labeled non-residential civil and military buildings on the map: a large water mill, a bath house, an Austrian imperial hospital (next to a church),

and a military barracks (kaserne) building. Images © Gesher Galicia and RJH.

A cluster of unnumbered (and uncolored) buildings probably owned by the Krasiński family in Rohatyn. Image © Gesher Galicia and RJH.

A few important omissions on the neighborhoods map are the houses numbered 1 through 6 in the property records but not indicated by numbered buildings on the cadastral map. We can suppose that the residential house of the landowning noble Graf (i.e. Count) in Rohatyn, Piotr Krasiński (and his family) numbered 1 in the property records is likely part of the complex of large buildings southwest of the market square; none of these buildings were numbered on the map but the Rohatyn local history museum and other historical analyses have linked these buildings to the local noble family (the Krasiński family also occupied three other residential houses which are numbered on the map). The buildings numbered 2, 3, and 5 in the text records were owned by a Rohatyn Christian parish and may have housed priests officially supported by the parish, but they are not numbered on the map. House number 4, which belonged to a Rohatyn school (unclear whether it was a civic organization or associated with one of the religious communities) and may have also housed a teacher, is likewise not numbered on the map. These omissions do not represent “ordinary” Rohatyn citizens, but might have given some additional texture to the interpretation of neighborhoods in the city.

Analysis and Observations

Quantitative analysis of the house number/name/community data and visual inspection of the modified historical map allow for a number of observations to be made about the geographic dimensions of Rohatyn in the mid-19th century, the demographic composition of its neighborhoods and suburban/rural areas, and the proximity of religious community residences to their houses of prayer. The excerpts from the map shown in this section illustrate some of the findings, but a close inspection of the complete interactive map will make those observations more clear:

Click here to launch the neighborhoods map in a separate window.

The interactive map can be zoomed in and out by clicking the + and – buttons at the upper left corner of the map window, or on many devices by double-clicking on the map itself with and without holding down a Shift key. The map can be panned in any direction by click-hold of a mouse or other pointer and dragging the pointer to a new location. An important map feature is the opacity slider in the upper right corner of the map window, which can be dragged to reveal a modern satellite image of Rohatyn on which the historical map is overlaid.

Quantitative observations:

Numbered houses are unique residences: The 1846 Rohatyn property registers identify 462 building owners who were resident in Rohatyn (i.e. they had Rohatyn house numbers) plus a much smaller number of people who owned property in Rohatyn but were officially resident in nearby villages (Babintsi, Perenivka, Pidhoroddia, Zaluzhzhia, and Verbylivtsi). On the 1846 cadastral map, there are only 7 legible house numbers which do not have corresponding data in the Rohatyn property registers (1.5%); these are likely either renters or errors in the register. Without the corresponding final-stage cadastral map which would show building parcel numbers, it is not possible to positively confirm the high residential ownership rate of houses in Rohatyn in the period, but no alternate scenario seems likely.

Gentiles in traditional and modern dress in Rohatyn and nearby villages in the first part of the 20th century.

Source: Opillya Museum photo archive.

In 1846, Jews lived in 203 houses in Rohatyn, and gentiles in 244 houses: Thus, the Jewish community was resident in about 44% of Rohatyn houses, with gentile houses making up nearly all the rest. Another 7 houses (1.5%) had residents of indeterminate nationality based on names, and as noted above an equal number on the map had no recorded name data from which to group the residents into communities.

Rohatyn exhibited moderate building wealth in the 19th century: Within the cadastral area of Rohatyn, there are almost 700 buildings listed in the property registers, meaning that more than 200 buildings were counted as property but not as residences; these are the religious community buildings and service buildings described above. Among the resident individuals and community organizations which owned more than one building are the Krasiński family (with 20 buildings), the Greek Catholic parish (with 13), the Roman Catholic parish (with 9), the Rohatyn Jewish community (with 6); the Rohatyn civic community (i.e. the city) owned one non-residential building. Private property owners thus held the majority of non-residential buildings; some Jews owned service buildings, perhaps to support their trades, but a much larger number of service buildings were owned by members of the gentile community.

Visual observations:

An excerpt from the map is shown here to illustrate these observations; the text continues below:

An excerpt from the modified map showing central Rohatyn and a portion of surrounding farmlands in 1846, with color-coded house outlines. Image © Gesher Galicia and RJH.

Rohatyn Jews always exhibited both tradition and modernity. Here, renowned Rabbi Meyer Shmuel Henne poses in Rohatyn with his visiting grandsons in 1932. Source: Henne Family Collection.

As of 1846, in Rohatyn there were no apparent restrictions on where Jews could live or own property: The presence of Jews in Rohatyn was recorded in the 15th and 16th centuries, and in 1633 Jews were granted municipal rights to establish a cemetery, to build a synagogue, and to trade in town; permission to own houses on the market square came a few decades later. Although a number of special taxes and restrictions on Jewish economic and religious independence were applied in the 18th century (and much later, during the interwar period), most of the restrictions were short-lived. Significantly, from the late 17th century (until the Holocaust) we are not aware of any historical limitations on where in Rohatyn Jews could live, and the neighborhoods map demonstrates this quite clearly for the mid-19th century. Thus in Rohatyn of that period there was no official or unofficial “Jewish quarter” where Jews were segregated, and there is no geographic evidence of other issues in relations between Jews and gentiles. This contrasts with some other places in Europe and even in Galicia, especially larger towns and cities, where civic authorities were granted the privilege to exclude Jews or restrict their trade or residency. For example, in Bochnia (in western Galicia between Kraków and Tarnów), legal prohibitions against participating in the salt trade kept Jews out of the town until the second half of the 19th century; in Gorlice, a bit further east, to avoid municipal laws Jews lived outside the town center until the second half of the 19th century, when they began settling near the market square.

Feige and Ze’ev Steinmetz of Rohatyn with their children ca. 1918.

Source: Steinmetz family collection.

Rohatyn Jews primarily lived on and around three sides of the market square: With only about ten exceptions, all of the Jewish families of Rohatyn in 1846 were resident around the historical town center and market square, probably because their economic life was generally associated with business, commerce, and especially trade. The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe notes that “in eastern Galicia and the Subcarpathian Rus’ region of Czechoslovakia a significant proportion of Jews made their livelihood by tilling the land and cutting timber”, and testimony by both Jews and Ukrainians about life in the villages of the Rohatyn district reports that some Jews who lived outside the city supported themselves partly or wholly through agriculture. But in Rohatyn itself, where 25~30% of the district’s Jews lived, as the map shows very few Jews were resident outside the urban core of the city. In fact, about 94% of Jewish houses in 1846 were built within a circle of 500m diameter centered on the 19th-century market square. Compared to the gentile population, which lived on urban and productive land covering about 150 hectares (about 375 acres) of Rohatyn’s cadastral area, the Jewish population lived on barely 10% of that total (about 15 hectares).

There was no area in Rohatyn which was entirely Jewish: Although there were large geographical areas of Rohatyn which were exclusively settled by gentiles, in 1846 even in the areas of the city where Jews were the majority residents, some gentiles lived alongside or near Jews – with the possible exception of the north-of-center section. Likewise, the religious buildings (synagogues and churches) of both communities had at least some neighbors of the other faiths.

Other notes and analysis limitations:

As noted in the Introduction above, the present study is a snapshot in time around 1846 where the best data set of residents’ locations is available, and similar analysis would be more difficult both earlier and later in history. While the visual results of the study are interesting and reveal something important about the Jewish community of the period, a review of other 19th-century records show that residency in neighborhoods and in individual houses was dynamic, even if the community trends were slow to change. Some houses show evidence of Jewish residency over six decades but other records reveal that some houses changed from Jewish to Ukrainian or Polish and back again over the course of only two generations. Hence the summary remark that the map presented here is a “snapshot”, even compared to other decades of the 19th century.

A bird’s-eye view of the destruction of Rohatyn in WWI; the view is from the Roman Catholic church tower on east side of the rynok, looking north. Source: Tomasz Wiśniewski Collection.

It is also important to recall that most of central Rohatyn was intentionally burned by retreating Russian troops during WWI, and when the city was rebuilt during the interwar period, for the most part only the streets and a few major buildings (e.g. churches and synagogues) were preserved. Based on an overlay comparison of the 19th-century map and modern satellite images, it is clear that individual house footprints and neighborhood construction in general were not preserved from before the war. It is currently unknown how Jews and gentiles resettled in Rohatyn during the rebuilding phase of the early interwar period.

Another important note is that as of 1846, Jews had not yet built homes in the “New Town” (Nowe Miasto) area to the west of the market square and alongside the Hnyla Lypa River; that would come later, if not before WWI then certainly after, based on the small number of recorded interwar addresses of Jewish families. A few street maps of interwar Rohatyn exist, but only major individual civic and religious community buildings are shown (no residential houses) and there is no associated demographic data.

Resources

Portions of the data included here were originally sourced by Gesher Galicia (GG); selections were indexed and published by the Rohatyn District Research Group (RDRG) and on GG’s All Galicia Database (AGD). Other portions of the data included here were originally indexed and published by Jewish Records Indexing – Poland (JRI-Poland).

- 1846 cadastral field sketch of Rohatyn: Central State Historical Archives of Ukraine in Lviv (TsDIAL) record 186.1.668; composite map assembled and published by GG; overlay version and reference page created by Rohatyn Jewish Heritage (RJH)

- 1846 Rohatyn alphabetical property owners’ register, with the village of Perenówka: TsDIAL 186.2.21a

- 1846 Rohatyn building parcel register (Bauparzellen Protocoll), with the village of Perenówka: TsDIAL 186.2.21b

- 1820 Rohatyn Franciscan survey: TsDIAL 20.9.189, partial index (sheets 1~35)

- 1870 Rohatyn voter lists (Spis Uprawnionych do Wyborcow Sejmawych): Polish State Archive, Wawel Castle, Krakow, Poland (record # unknown), partial index (Jewish names only)

- 1859-1937 Rohatyn vital records (birth, marriage, death): Polish State Archives, comprising a collection of records from several sources sourced and indexed by the RDRG, including data from:

- Rohatyn Interactive Data Map 1846: data prepared by RDRG and RJH; web programming by GG

- Rohatyn Jewish Holocaust Victims List (Unknown Original Source): Ukrainian State Archive of Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast (DAIFO) record R98.1.2, transcribed and transliterated by RJH

- 1944 Soviet Extraordinary State Commission Report Fragment on Rohatyn: State Archive of the Russian Federation (GARF) record R-7021-73-65, acquired by the RDRG from the Yad Vashem documents archive; then transcribed, translated, and transliterated by RJH

- 1945 Soviet Extraordinary State Commission Report on the Rohatyn District: GARF record R-7021-73-13, acquired by RJH from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) collection RG-22.002M, accession 1995.A.1265; Reel 11, section 13; and from Yad Vashem document collection Item 13224740, file number JM/17303; then transcribed, translated, and transliterated by RJH

- Jewish and Ukrainian Memoirs of Jewish Life in Rohatyn; especially Donia Gold Shwarzstein’s Remembering Rohatyn and Its Environs, and the Yizkor Book for Rohatyn: The Community of Rohatyn and Environs (Kehilat Rohatyn v’hasviva)

- Cadastral Maps in Genealogical and Historical Research; Jay Osborn and Marla Raucher Osborn; proceedings of the conference “Zagadnienia Religijne i Narodowościowe we Współczesnych Badaniach Polskich, Słowackich i Ukraińskich na Terenie Euroregionu Karpackiego: Aspekt historyczny, socjologiczny i politologiczny” (Religious and Nationality Issues in Contemporary Polish, Slovak and Ukrainian Research in the Carpathian Euroregion: Historical, Sociological and Political Aspects); Jarosław, 2017

- The Habsburg Cadastral Survey and Map Initiative, Gesher Galicia Map Room

- Stages of Cadastral Map Development, Gesher Galicia Map Room

- Cadastral Map Legends, Gesher Galicia Map Room