Rohatyn Jewish Heritage participated on December 11, 2017 in a follow-up roundtable titled “Saving Jewish Cultural Heritage”. The roundtable was held at the office of the Honorary Consul of Israel in Lviv, where earlier this year a first roundtable was convened to review local Jewish heritage projects, and to exchange strategies for meeting challenges faced in cities and towns to raise funds, leverage resources, and connect with the Jewish diaspora. All of the participants in this second roundtable have been active in Lviv, in the Lviv Oblast, and/or in western Ukraine, and like Rohatyn Jewish Heritage, many had participated in the first roundtable. A key topic of discussion for this session was cooperation between activists to advance Jewish heritage projects in the region in 2018.

![]() Ця стаття також доступна українською.

Ця стаття також доступна українською.

There were 20 roundtable participants, including representatives of city and regional governments, an Israeli Jewish leader with roots in the region, members of the Lviv Jewish community, local and regional activists and volunteer organizations, local filmmakers, and staff from the All Ukrainian Jewish Charitable Foundation “Hesed-Arieh” of Lviv, one of the co-organizers of the event.

Presentations were made by activists in the cities of Dobromyl, Lviv, Lutsk, and Rohatyn (all of whom attended the first roundtable in February), and by new participants from Radekhiv, Rudky, and Stryi. Each discussed the history of their local Jewish heritage projects, accomplishments and setbacks in 2017, and plans for 2018. Introductory remarks were made by administrative representatives of the City of Lviv and the Lviv Oblast:

For the City of Lviv, Deputy Mayor Andrij Moskalenko noted that for 2018 the City is planning a commemoration at the site of Lviv’s wartime Janowska concentration camp, to coincide with the 75th anniversary of the camp’s liquidation. Review is also in progress to designate a final resting place for Jewish headstones recovered around the city in 2017 by the Lviv Volunteer Center (LVC), which may include construction of a memorial at the new Jewish cemetery at vul. Zolota (the cemetery commonly known as “Yanivska”). He also mentioned a proposed joint heritage project between the cities of Lviv and Uman.

During discussions at the roundtable, Alexander (Sasha) Nazar of the LVC asked about obtaining city permission to lift the recovered headstones upright, and the LVC’s desire to see a section of the cemetery dedicated to these recovered headstones. Mr. Moskalenko proposed that the LVC create a committee with his office to discuss these issues outside the roundtable. Mr. Nazar also asked whether the LVC may speak directly with the builder involved in a new construction project at vul. Lychakivska 33, where it is known that Jewish headstones are in the pavement; Mr. Moskalenko agreed.

On behalf of the Department of Culture, Nationalities and Religions of the Lviv Regional State Administration, Lesya Kornat expressed her office’s continued support for Lviv regional Jewish heritage projects. During discussion, she was asked by Tetyana Sadovska, an individual activist in Radekhiv, whether there are any funds budgeted for 2018 for restoration of old cemeteries in the Lviv region, noting that the city of Radekhiv has shouldered the costs for a number of projects in town but needs external support to move these forward and to initiate new projects. Ms. Kornat explained that while there is a budget for religious heritage projects within the Department of Culture, the budget category does not specifically cover cemetery restoration; she suggested that application be made to her department within the budget category of “churches and sacred places” which has funding for projects.

One of the event organizers, Wito Nadaszkiewicz, executive director of Law Craft Legal Services in Lviv, then raised the topic of “self-government” and asked Ms. Kornat to comment on the status of transferring decision-making functions relevant to heritage from the Lviv city and regional level to the local town level. Ms. Kornat explained that the process had begun, but that there were structural issues at the town level for some places which were inhibiting the transfer of power; namely, where there is no specialist or department of culture or preservation in place at the local government level (but in place at the Lviv city or regional level), and no budget for heritage preservation. She invited representatives of towns facing these structural limitations to meet with her and her counsel outside the roundtable to discuss these issues further.

Representing Jewish descendants abroad with roots in western Ukraine, Dr. Aharon Weiss spoke about the great interest and attention being paid by the diaspora to heritage projects in the region, especially in the regions of historic Galicia and nearby Volhynia. He emphasized that Galicia and Volhynia hold a “special place in the hearts of Jews in Israel” and that the preservation of Jewish heritage in these regions is the “most important goal.” Dr. Weiss noted that it takes partners for heritage preservation projects to succeed, requiring the cooperation of regional and city administrations, the involvement of the local Ukrainian population, and the support of Jewish descendants living abroad, citing as successful examples of such collaborative projects the cities of Dobromyl (discussed further below) and Zhovkva. He also noted the growing interest of Israelis in heritage tourism in western Ukraine, and the desire of many such tourists to have a day during their trips for hands-on participation in heritage projects, such as a clean-up at a Jewish cemetery. Dr. Weiss stressed that “it is up to us to show them what is here today” and to actively reach out and share information about planned work camps like those organized by the LVC last summer at the Jewish cemetery and synagogue in Staryi Sambir. He concluded by saying that bringing Jewish heritage tourists “on board” to participate in heritage work camps would be a tremendous boost of manpower for these projects, and also a way to build bridges and goodwill between Ukraine and Jewish communities abroad.

Rohatyn Jewish Heritage gave a summary of our projects in Rohatyn in 2017, which included completion of non-invasive georadar surveys at the Jewish mass grave sites by an archaeology team from the UK’s Staffordshire University (the final report to be published on our website before year-end); ongoing Jewish headstone recovery progress; our collaboration with Rohatyn’s new local history museum “Opillya” for the creation of a permanent exhibit on the area’s Jewish history; and the signing of an agreement of cooperation with City of Rohatyn. For 2018, we highlighted a start to rehabilitation of Rohatyn’s old Jewish cemetery, including a planned clearing of the site in late summer by the U.S. Christian non-profit organization, The Matzevah Foundation. We also noted that Rohatyn Jewish Heritage has submitted a proposal to the Polish stone-working NGO Stowarzyszenie Magurycz to include a work camp at Rohatyn’s new Jewish cemetery in their 2018 project schedule; we hope the Magurycz volunteers will be able to lift and re-set half a dozen large fallen granite headstones at the new cemetery.

We concluded our presentation by encouraging other roundtable participants to contact Lublin-based Shtetl Routes to get their projects added to the new cross-border guidebook of Jewish heritage sites. Rohatyn Jewish Heritage brought ten copies of Shtetl Routes’ new book to the roundtable for distribution, and we delivered an additional eight copies to the LVC a few days later. The guide, geared toward heritage educators, tour operators, and tourists, includes chapters on Jewish history and heritage sites in nearly two dozen Ukrainian cities and towns, including Rohatyn. The guidebook is currently available in Ukrainian and Polish; an English-language version is due out soon. This past summer, Rohatyn Jewish Heritage hosted twenty educators, guides, and professionals in heritage tourism, spending an afternoon showing them around Rohatyn as part of an education program organized by Rootka – Following Heritage Traces, affiliated with Shtetl Routes.

On behalf of Dobromyl, a presentation with slides was made by Liubomyr Yatsynych. He discussed the building of the memorial wall of recovered headstones at the Dobromyl Jewish cemetery, a big project realized in partnership with an American Jewish descendant of Dobromyl, Arthur Kurzweil, together with local residents and the LVC. The wall took five months to build and is faced with Jewish headstones recovered from sites in town. Mr. Yatsynych noted Dobromyl’s decision to focus on one heritage project per year to ensure that resources (manpower and finances) are not over-extended and projects put at risk. Among the other projects in his presentation was the summer 2017 unveiling of a memorial plaque at the site of Dobromyl’s destroyed Grand Synagogue. The event was attended by Dobromyl clergy, local government administrators, residents, members from the Lviv Jewish community, and other volunteer organizations including Rohatyn Jewish Heritage. The Dobromyl synagogue history project also produced a 300-page book on Dobromyl’s Jewish history, due out this month. Proposed projects for 2018 include the removal of Jewish gravestones from a lightweight auto bridge built in 1949 which is located in a residential part of the town, and creation of signage for the Dobromil Jewish mass grave. Mr. Yatsynych asked Ms. Kornat whether there might be regional financial support for dismantling the bridge, recovering the headstones, and reconstruction. She responded positively and proposed further discussion outside the roundtable for this project. Mr. Yatsynych concluded by noting that, before the Dobromyl projects, about 80% of the town’s residents knew nothing about the existence of the city’s prewar Jewish community – now they do.

During discussion, Mr. Nadaszkiewicz noted that the challenges in Dobromyl are typical of other cities and towns in western Ukraine seeking to launch and advance heritage projects: How to find supporters for these projects, including Jewish descendants? These challenges are particularly acute for the smaller cities and towns which tend to be isolated and lacking visibility outside the immediate surroundings.

Seated next to Mr. Yatsynych was a woman named Oksana Oziemblovska, and although she did not make a presentation, we learned later that that she is looking to develop Jewish heritage projects in her town of Nyzhankovychi, 20km from Dobromyl and very near the border with Poland, perhaps with activists in Dobromyl and Khyriv. We hope that at the next roundtable, Ms. Oziemblovska will present about her issues and ideas.

For Radekhiv, a presentation with slides was made by Tetyana Sadovska, who we had visited last month. In autumn 2016, about 100 Jewish headstones were recovered by Radekhiv residents from a pathway made across the Ukrainian cemetery under the Soviets. The cemetery had already been the focus of a project of memory initiated by Ms. Sadovska (the cemetery includes Ukrainian, Czech, German, and Polish graves, as well as soldiers’ graves). Working together with the city of Radekhiv, her project produced a film called “Trodden History” and a book. Thereafter when the Jewish headstones were uncovered, she found her memory project had suddenly grown bigger and more complicated than she had imagined. Not far from the town center is the vacant former synagogue (today in private hands) and the town’s Jewish cemetery.

Ms. Sadovska would like to see the recovered headstones used to build a wall of memory, preferably at their recovery site in the Ukrainian cemetery, or alternatively, near the Jewish cemetery. She would also like to see the former synagogue turned into a cultural center or education space for residents and visitors to learn about Radekhiv’s multicultural history. For these and other ideas associated with developing the heritage of the city, Ms. Sadovska is working with the city of Radekhiv, but external support is needed for these projects to move forward. There is a second pathway at the Christian cemetery which also appears to have Jewish headstones beneath concrete and top soil, which Ms. Sadovska hopes will be excavated in 2018. Other projects she would like to see realized include creation of an online map of the heritage; cleaning and vegetation clearing at the cemetery; and heritage signage. Ms. Sadovska concluded her presentation by thanking Rohatyn Jewish Heritage for promotion of her projects on social media, which put her in contact with some Radekhiv Jewish descendants abroad, who will hopefully become supporters. She expressed her personal desire to see cooperative, cross-cultural projects which “popularize our common culture”.

For Rudky, a presentation with slides was then made by Volodymyr Kogut, who has been documenting Rudky’s Jewish past for several years. Jay and I first met Mr. Kogut at the LVC’s clean-up project at the Staryi Sambir cemetery last summer, and subsequently we visited him in Rudky to see the Jewish heritage sites. The Jewish cemetery in town was built over by high-rise apartments in the Soviet era; it is accessed over a foot bridge known to the Rudky residents as the “Jewish bridge”. There is also a surviving empty former synagogue building in Rudky, today privately owned; before the Holocaust there had been four synagogues, plus a Hasidic court, a Tarbut school, and a number of Zionist organizations. Through his research, Mr. Kogut has mapped the prewar Jewish neighborhood, a number of Jewish-owned buildings, and the boundaries of the wartime ghetto. From his research, in 1939 Rudky’s Jews accounted for 52% of the town’s population. There were only 18 Jewish survivors of the original prewar community.

About 4km outside of town, on the main highway to Lviv, there is a mass grave. In the 1990s, Jewish gravestones were recovered from the pavement of a Rudky parking lot behind a building which had served as Gestapo headquarters during WW2, as in Rohatyn; at that time, Jewish survivors and descendants returned to Rudky to install a memorial space incorporating the recovered headstones at the mass grave site, and a large plaque dedicated to the destroyed Jewish community. Today, the site is so overgrown that it is no longer visible from the highway; most of the headstones are inaccessible and illegible due to mold and moss. Mr. Kogut would like to see a number of projects realized in 2018, including clearing of the mass grave site, cleaning and translating of the headstones there, and perhaps the creation of a new memorial similar to that in Dobromyl. He also hopes to write a book about Rudky’s Jewish history for a Ukrainian audience, and is eager to network and partner with other locations in the region with Jewish heritage projects, such as Staryi Sambir. Mr. Nazar of the LVC proposed to include Rudky’s mass grave on the LVC work camp projects for next year.

For Lutsk in the Volyn Oblast, a presentation with slides and video was made by Tatyana Plotnykova and Sergei Shvardovskiy, Executive Director of the Lutsk Jewish community; their heritage activism in Lutsk is in its eighth year, focusing primarily but not exclusively on the Jewish cemeteries and sites of WW2 mass executions, including documentation and commemoration. Some 80% of Lutsk’s residents would still be unaware of the city’s prewar Jewish presence if not for their projects. Ms. Plotnikova and Mr. Shvardovskiy both noted the growing interest of the Jewish diaspora in visiting Lutsk, driven by genealogy and roots research. Both activists have been working with Lutsk teachers and museums. Despite a clean-up of the Jewish cemetery, the cemetery has filled with vegetation (as at several other heritage sites discussed at the roundtable). To try to avoid this result from repeating, the pair now are focusing on smaller projects (such as signage) which are less expensive to implement and do not have long-term maintenance issues and recurring costs.

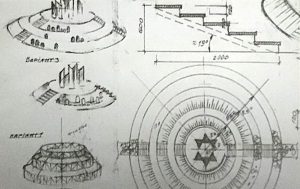

Unlike Galicia, the Volyn region experienced larger participation by Ukrainians in the Nazi’s destruction of the Jewish community. Past collaboration hinders openness now in the local population to support Jewish heritage projects. According to Ms. Plotnikova and Mr. Shvardovskiy, several of their projects have encountered opposition within local government administrations. For example, about 500 gravestones were discovered at a former military site which belonged to the municipality; it wasn’t until the site passed into private ownership that they were able to negotiate their removal. The headstones are in storage now, awaiting relocation. Ms. Plotnikova and Mr. Shvardovskiy also described their unsuccessful 7-year negotiation with the city concerning the Lutsk old Jewish cemetery, today covered by the Palace of Culture. Mr. Kogut asked whether their strategy might have been more successful if they had negotiated not for return (restitution) of the site, but merely support for recovery of any surviving headstones and documentation of the historic nature of the site. Ms. Plotnikova and Mr. Shvardovskiy explained that they tried all these approaches, to no avail. Their 2018 project envisions creating a memorial mound made of recovered headstones; professional plans have been drawn, and the project, being a mound, complies with Jewish law forbidding digging at the cemetery. To date, the local administration opposes the project and declines to give permission for transfer of a portion of the cemetery site for the project to be realized. The presentation concluded with an explanation that, for Lutsk, their projects need not only financial support, but also regional assistance to negotiate further with the local government administration.

Petro Kuritnyk, a deputy with the local administration of Stryi, then made a presentation as a new participant to the roundtable event. The large synagogue ruin in town has been a primary focus of his heritage projects, beginning with renovation of the original metal entrance gate. Since then he has also led or participated in clearing of garbage inside the former synagogue, as well as cutting and clearing of trees and shrubs in and on the building ruin together with the LVC and local student volunteers from Stryi’s “Youth National Congress”. In September of this year, American Jewish descendant Donna Kerner visited Stryi, and with her support Mr. Kuritnyk brought equipment inside the synagogue that could reach and remove the plants growing out of the bricks at the top of the tall structure. In the 1990s, signs were affixed to the synagogue entrance by Israeli survivors and descendants. Mr. Nazar added that continuing the LVC’s work on Stryi’s synagogue is already part of their 2018 projects.

Among the issues that need to be addressed is how to protect residual frescoes on the inside walls of the roofless synagogue, which are currently open to the elements and deteriorating. Should the ruin be roofed, or is there a less expensive but satisfactory solution such as an overhang that can be explored? What about opening the basement space so humidity cannot build up? Due to moisture, some bricks are loose and falling out of walls and the synagogue support structure; this problem needs a solution if the integrity of the building and its decorative elements are to be preserved. Asked about the attitude of the Stryi government administration, Mr. Kuritnyk said it was open and supportive of his work. In the discussion, Mr. Kuritnyk agreed that a group would be formed to approach the city administration to discuss planning and ideas. With regard to the Stryi Jewish cemetery and the mass grave at vul. Zelena, Mr. Kuritnyk said that for 2018 he would like to see a clean-up and headstone project initiated at the cemetery, and additional informational signs installed at the mass grave site. Mr. Nadaszkiewicz asked what would be the long-term usage of the synagogue; Mr. Kuritnyk suggested an art center and cultural space with an exhibition on Stryi’s Jewish community history, much like the LVC hopes to establish at the former synagogue in Staryi Sambir.

Recovery of Jewish gravestones by the LVC from a courtyard in Lviv. Photo © 2017 Christian Herrmann.

A review of projects organized by the Lviv Volunteer Center of Hesed-Arieh in the city of Lviv and around the region was made by Sasha Nazar, as the final presentation of the roundtable. In Lviv city, LVC projects for 2018 will continue work progressed in 2017, including recovery of Jewish headstones from a courtyard, plus negotiation and further recovery from under vul. Barvinok, which is likely fully paved with headstones; additional recoveries are anticipated at vul. Lychakivska 33 and elsewhere as more local residents report stones at or near their residences. As noted above, hopes and plans also include the establishment of a dedicated place of return for the recovered headstones at the new Jewish cemetery (“Yanivska”) at vul. Zolota, erection of the recovered stones, the possible installation of a fence, and a focused cleaning and clearing of the cemetery to reduce damage to existing stones. Other work continuing in 2018 in Lviv includes preparation for and installation of a new heating system in the former “Jakob Glanzer” synagogue on vul. Vuhilna, now a cultural center. Rehabilitation of the shochet’s house next door to the synagogue continues, including the repair of the roof to integrate two separate sections (already completed), plus installation of pillars and beams to brace the brick structure, preparing and pouring a new a concrete floor, and other repairs to reverse damage from post-war modifications during the building’s misuse before it was acquired for the cultural center. An original ornamental metal gate to the shochet’s house has already been stripped and cleaned, and awaits further detailing and installation once the house is stable and enclosed.

Discussion then turned to group-level goals and plans for 2018, led by Mr. Nadaszkiewicz with assistance from Mr. Nazar. Proposals included:

- publishing in yearbook form a collection of the projects presented at the roundtable (perhaps including the histories of the projects, 2018 project goals, and contact information for project leaders, local activists, specialists, and heritage supporters) as well as useful methods, resources and links for new activists in heritage preservation (how-to advice on initiating involvement with local government administrations, learning about legislative and legal considerations and protections, accessing maps, managing public relations and social media, fundraising, and developing an internet presence);

- drafting a memorandum of those present at the first and second 2017 roundtables, including new participants at the latter such as Rudky, Radekhiv, and Stryi, and proposing new location additions for 2018’s roundtable;

- scheduling and publicizing a list of regional Jewish heritage work camps, including those proposed by the LVC for 2018 in Rudky and Stryi, with suggestions for others such as Drohobych or Boryslav;

- organizing heritage tours for Jewish visitors to regional project sites, and engaging them in work camps;

- installing signage at heritage sites with QR codes directing visitors to websites with information on the history of the site and project contacts; and

- drafting a sample letter which can be used for mailing to embassies, diplomatic institutions, NGOs connected with heritage, Jewish genealogy organizations, and twinned towns, summarizing our roundtable’s purpose, identifying the participants, and requesting support and cooperation.

We give sincere thanks to our interpreter for the day, Natasha Tolok, for enabling us to participate in the roundtable and related discussions. We owe a debt of gratitude as well to Sasha Nazar of the Lviv Volunteer Center of Hesed-Arieh and Wito Nadaszkiewicz of Law Craft LLC for the invitation to join this event. We look forward to advancing and advocating collaborative projects for 2018 with the other participants.

See also the cross-post about this event on the Jewish Heritage Europe news page; a warm thank-you to Ruth Ellen Gruber for the coverage.